By Eric Kraan — Whether you understand Utah’s present traffic safety shortcomings as a recent uptick in traffic fatalities or see it as a long-term trend, it is undeniable that changes are necessary.

The Utah Department of Transportation’s (UDOT) 2016 Strategic Safety Plan set a goal to reduce fatalities by 50% by 2030. This meant, back then, an average annual reduction in fatalities of 2.5%. Today, UDOT would need to reduce fatalities by about 10% annually to meet this goal.

In simple terms, the current strategy has failed.

Thankfully, the new National Roadway Safety Strategy offers the transportation community an opportunity for meaningful change. We must seize the moment.

Change is Disruptive – Resistance a Choice

The National Roadway Safety Strategy calls for state and local transportation organizations to implement a radically new Safe System Approach and realign their safety culture to these six principles:

- Deaths and serious injuries are unacceptable

- Humans make mistakes

- Humans are vulnerable

- Responsibility is shared

- Safety is proactive

- Redundancy is crucial

Long-held values of the transportation profession are most likely to be challenged by principles #2 and #4, and as a result, the decision-making process could suffer from cognitive biases.

If the safe system approach is to succeed, it is critical to identify and proactively address this safe system fallacy.

Let us first consider what principle #2; humans make mistakes, asks a transportation professional to accept:

Thus, the insistence by many DOTs to overly rely on educational campaigns aimed at changing roadway user behavior (an inevitable external factor) to reduce the negative outcome of crashes is not part of the safe system approach.

Let us now consider what principle #4; responsibility is shared, asks a transportation professional to accept:

Organizations that engage in cognitive bias while defining the second principle will find it hard not to double down and assign responsibility to people who inevitably will make a mistake, confirming the existence of a safe system fallacy.

Self-serving bias is the tendency to attribute internal, personal factors to positive outcomes but external, situational factors to negative outcomes.

Are the Utah Department of Public Safety and UDOT entangled in a safe system fallacy?

On May 18th, the Utah Department of Public Safety (DPS) presented a report to the Utah State Legislative Transportation Interim Committee titled: The National Roadway Safety Strategy — How Utah is Applying the Principles. This document depicts heavy reliance on efforts to influence road user behavior, such as; community education, media campaigns, and high visibility enforcement campaigns.

The DPS also denies that the National Roadway Safety Strategy offers anything new to the state’s Zero Fatalities Strategy:

These principles are not new initiatives in Utah, as they align with the current strategies of the Department of Public Safety and the Utah Department of Transportation.

The DPS continues, in predictable fashion, to double-down and redefine the fourth principle as:

Shared responsibility crosses all stakeholders, including law enforcement agencies, local government, advocacy groups, nonprofits, health and medical, emergency medical services, and most importantly, the drivers and road users themselves. (Stress added)

This evidence suggests that UDOT and DPS are entangled in the safe system fallacy. Academic papers point out the need of individuals and organizations become aware of this condition, and for Federal Agencies and State Legislators to provide them the appropriate tools to correct the condition.

Fortunately, Federal agencies are voicing out awareness of this problem. NTSB Chair Jennifer Homendy has voiced her concern that the highway safety community remains confused about how the Safe System Approach differs from flawed traditional approaches, such as Utah’s Zero Fatalities:

We need to ditch our overreliance on ineffective education and enforcement campaigns to address increasing death and look to much better, long term solutions, Chair Homendy stated.

Similarly, the FHWA has shared the correct definition and context that state agencies, like UDOT and the DPS, must employ when defining the fourth principle:

The intent is to de-emphasize the role of individual road users and rebalance the distribution of responsibility for road safety outcomes. While individual users play a role and their behavior is wrapped into the design of vehicles and roadways, a systems approach assigns responsibility to those who plan, build, and maintain the transportation system and the vehicles that travel upon it.

Overcoming Safe System Fallacy

As we stated already, overcoming cognitive biases requires awareness made with some sort of benchmarking tool to help gauge the decision-making process.

The Vision Zero Network, for example, has long identified the lack of a best practice benchmark as one of the most pressing obstacles to its successful implementation.

What is a best practice benchmark, and how can it help the safe system approach succeed?

Safe System Benchmarks

A safe system approach must provide a planned process for organizations to compare their health and safety processes and performance with others and learn to reduce roadway fatalities and serious injuries. A Safe System Benchmark must answer the following questions:

- What does it want to achieve? This question enjoys universal agreement – ZERO fatalities.

- What to benchmark against? The yardstick must embody the values of the system it tries to measure.

- The cost of benchmarking? It must be cheap enough to implement, but not too cheap to fail.

- How will a benchmark improve compliance and reduce costs? A safe system is an efficient system.

Lamentably, the US DOT did not provide a safe system benchmark to assist state and local stakeholders overcome a potential safe system fallacy when implementing the National Roadway Safety Strategy. Therefore, it is necessary to search elsewhere for feasible solutions to this troublesome issue.

A reasonable approach calls for narrowing my search to places where the safe system approach has seen success and comparing their strategies to ours: The Netherlands was an obvious first choice.

First, there is no reason why Dutch transportation professionals would be less prone than their American counterparts to find themselves entangled by a safe system fallacy. Examining their safe system approach may provide evidence of a safe system benchmark, and explain how their professional transportation community has been given the tools to overcome this fallacy.

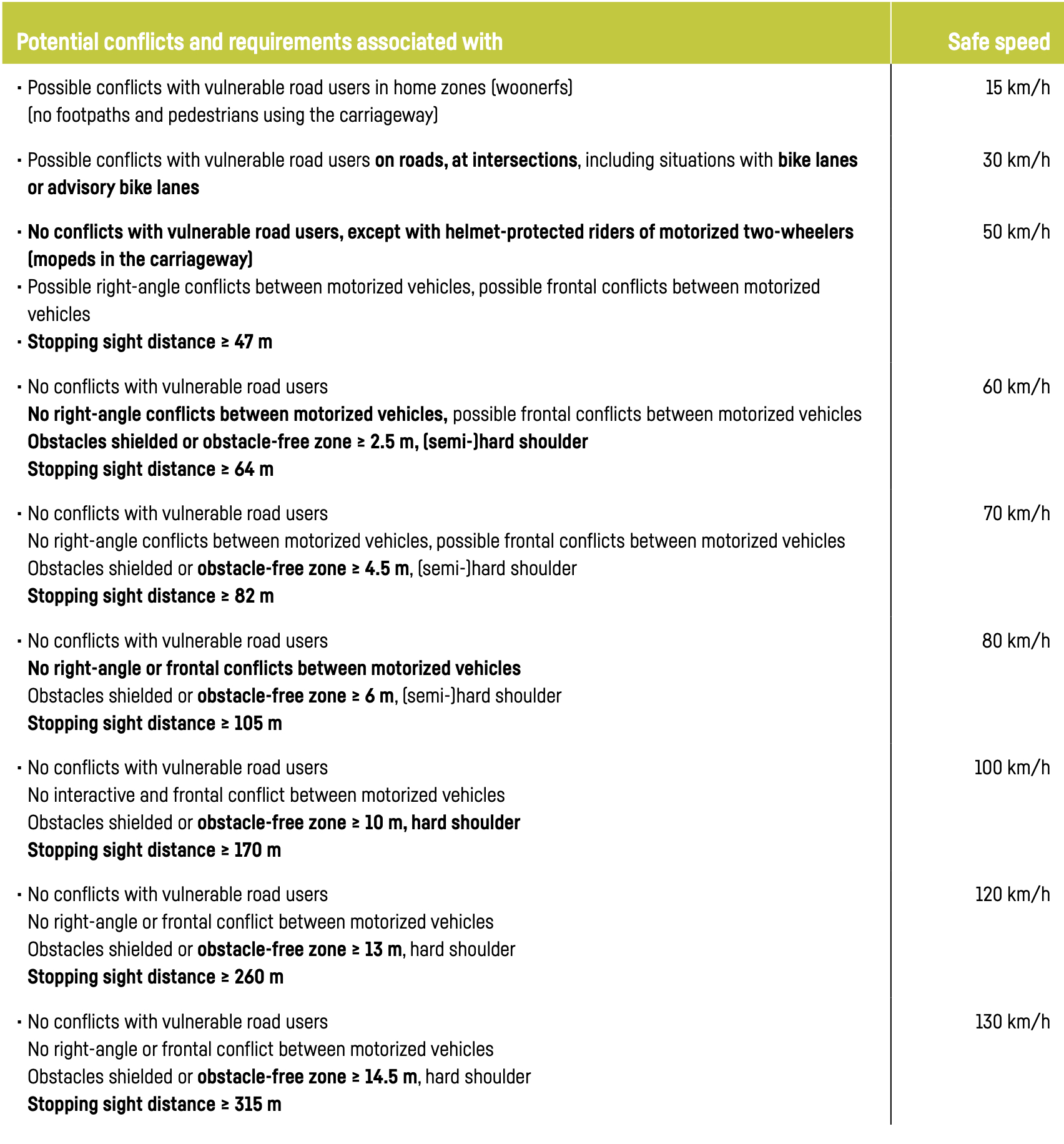

The Dutch Sustainable Safety 3rd Edition – 2018 to 2030 is their national safety strategy, and within it we can find a table that provides the benchmark that meets our paramenters.

The advanced vision for 2018-2030, SWOV.nl

How does this table answer the four questions of a safe system benchmark?

- It agrees with the goal of achieving Zero Fatalities.

- It creates a yardstick that embodies the values of the safe system approach and measures tangible progress towards the creation of a safe roadway system.

- It is data-driven and requires almost no upfront cost since it uses established and generally accepted scientific information. Further, benchmarking the current inventory of existing roads and new projects can also be done at little additional expense.

- Adopting this safe system benchmark improves transparency: the public can easily compare an existing or proposed roadway against a simple-to-read table. It improves accountability: transportation agencies are held accountable only for internal elements they control. It improves budgeting: roadway inventory can be prioritized based on a safe system rating.

Conclusions

The success of a safe system approach requires that transportation professionals, such as UDOT and the Utah DPS, be able to overcome a safe system fallacy. The US DOT appears to recognize this problem but has not provided a safe system benchmark to assure compliance with the National Roadway Safety Strategy.

As a result, it is up to the public to pressure State Legislators into adopting a safe system benchmark, similar to the Dutch approach, to safeguard public safety and prevent state transportation professionals from stalling their efforts by engaging in cognitive biases.