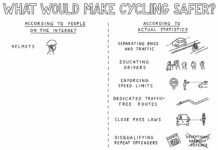

By Charles Pekow — A federal study conducted in Texas found that separated bike lanes and mixing zones at intersections significantly reduce the risk of crashes. The report, released by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and titled “Development of Crash Modification Factors for Bicycle Treatments and Intersections,” concludes that these treatments are economically feasible. However, other safety features, such as chevrons (angled stripes on the road), extension lines in crossings, colored lines, and other types of bike lanes, did not make much difference.

A companion study in six cities in Virginia, however, found no methods that significantly reduced crashes. The research team noted that it might not have enough crash data to definitively conclude that the methods don’t work, and an unknown number of crashes went unreported, possibly skewing results.

The researchers highlighted the use of different counting methods in the two states, relying on bicycle counts in Virginia and using their own demand models in Texas.

Meanwhile, another FHWA-sponsored study found that converting a standard bike lane into a protected one can cut crashes in half. The research team, examining six cities, including Denver, found that all it takes is adding flexible posts. Additionally, other measures to separate bike lanes proved effective, as reported in “Developing Crash Modification Factors for Separated Bicycle Lanes” (https://highways.dot.gov/media/30486).

The study suggested that the results in Denver weren’t as clear as for the other cities, possibly due to Denver’s climate and elevation. However, it also noted that bike crashes are less likely to occur with multiple auto lanes on the road, parking banned on at least one side of the street, and in industrial or public use zones, as opposed to mixed land-use areas.

Intersection Safety Challenge

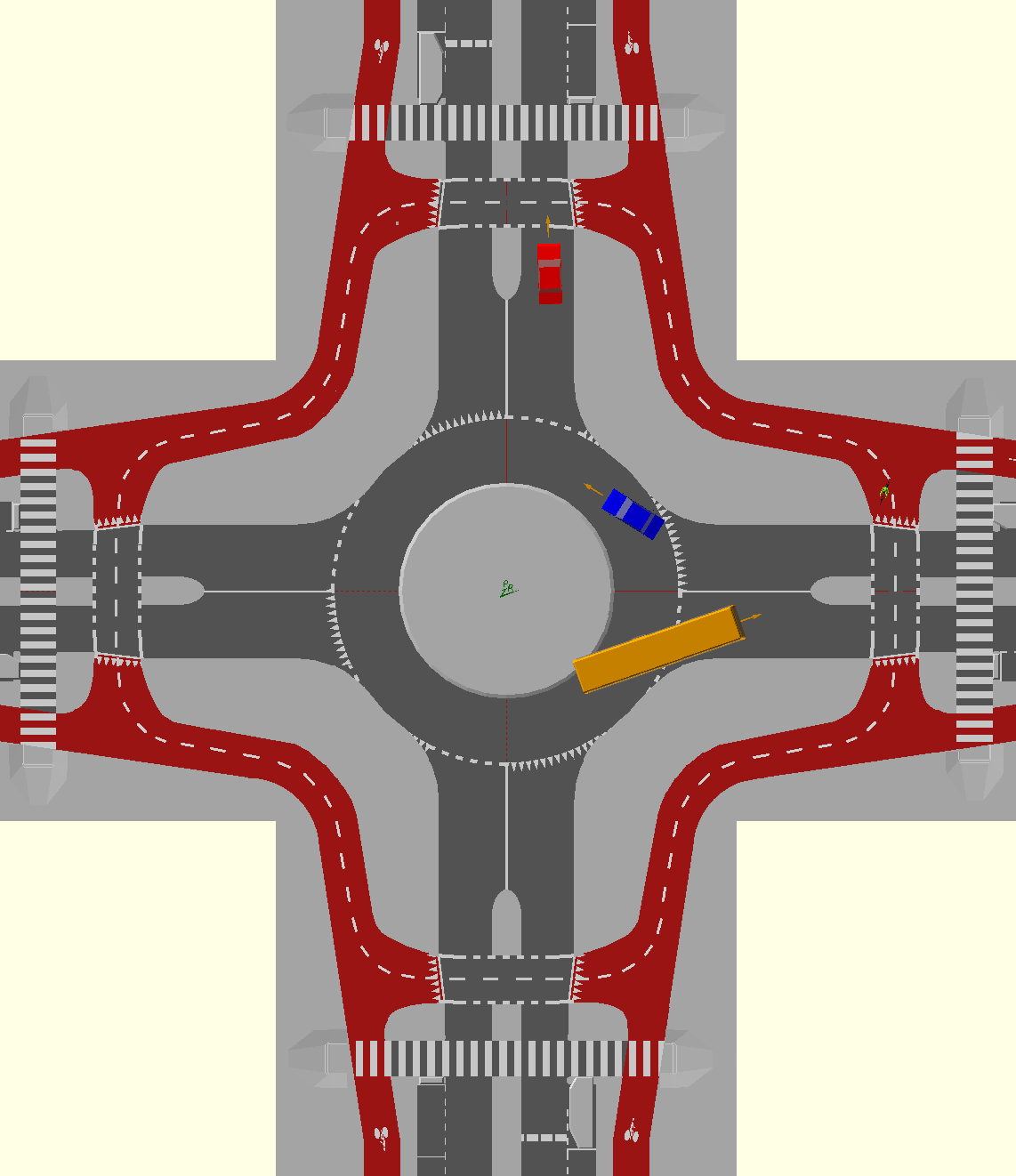

Also in the realm of intersection safety, some innovators will receive federal grants next year to develop technology for safer intersections for bicyclists. The U.S. Department of Transportation’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology is considering funding 120 concept papers received from academia, business, and government in response to a call for ideas under a new Intersection Safety Challenge – System Assessment and Virtual Testing Competition.

Participants will develop and improve algorithms to detect, localize, and classify “vulnerable road users” and autos based on government sensor data. The programs will use the data and algorithms to determine hazardous intersections. Cyclist deaths are on the rise, increasing by 2 percent from 2020 to 2021.

Ideas can include installing improved sensors to detect cyclists and others, using artificial intelligence to anticipate problems, and creating new safety systems that can be widely and inexpensively replicated.

The DOT can award up to $6 million in grants of up to $100,000 for projects enhancing holistic intersection safety.

Details can be found at https://portal.challenge.gov/public/previews/challenges?challenge=06326f1b-72bb-4d68-aa8b-cb67daeb286c

Meanwhile, an FHWA-funded research project at the University of Utah reported that crashes involving right-turning autos were “less severe” to cyclists and pedestrians than crashes involving left-turning autos or those going straight. The study surmises that’s because cars are moving more slowly when turning right and shorter exposure time. University researchers looked at data from about 2,200 incidents in Utah between 2010 and 2019. They found that the issue had scarcely been studied before.

Separated bike lanes and median strips tended to decrease bike incidents, while higher speed limits and the presence of bus stops and driveways increased danger. As you might expect, the higher the population and number of bicyclists, the more crashes – but not per capita. Statistically, there seems to be “safety in numbers” for cyclists, though obviously the more cars, the more crashes. The presence of nearby houses of worship decreased crashes, though it’s not known why. “More crashes were observed at intersections in neighborhoods with lower household incomes and more people of Hispanic or non-white race/ethnicity,” the report says.

Safety was enhanced somewhat by clear crosswalk markings. But factors such as right-turn lanes, bike lanes and ramps didn’t seem to matter much.

The project recommends that “if both bike lanes and dedicated right-turn lanes are present at an intersection (and unless the bicycle and right-turn movements are controlled by separate signal phases), the right turn lane should be on the right side of the bike lane (unless they are in a shared lane), and right-turning traffic should be directed to yield to bicycles and cross the bike lane prior to the intersection.”

Find Right-Turn Safety for Walking/Bicycling: Impacts of Curb/Corner Radii and other Factors at https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/72595