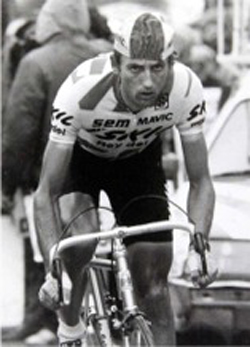

By Dave Campbell — The 1989 Tour de France is widely held as the greatest Grand Tour of all time. With Greg Lemond’s eight second margin of victory, most people also believe that it was the closest. That honor, however, belongs to the 1984 Vuelta a España. The Vuelta has been held in September since 1995, but the previous fifty editions (the race was first run in 1935) were held in the cold and wet of early spring, usually from mid-April to early May. The 1984 Vuelta, the 39th edition, was won with a mere six-second gap by Frenchman Éric Caritoux of the Skil-Sem-Mavic-Reydel team.

The 23-year-old climbing specialist from Carpentras was in his second year as a professional in 1984. He won the Mont Ventoux stage of the Paris-Nice while helping his team captain Sean Kelly of Ireland win the race overall for the third year in succession. Despite domestique duties, he notched a fine eighth place overall for himself. Kelly was on a spring rampage (he would ultimately win 33 races!) that earned him the nicknames “King Kelly” and “The New Cannibal”. Caritoux served as a super domestique in March and April, aiding Kelly’s victories in the Critérium International and the Tour Pays Basque, where the young French rider finished a fine 6th himself. Skil team boss Jean de Gribaldy, the legendary “Viscount”, then gave Caritoux a few weeks off, with his next start scheduled for the Tour of Romandie in Switzerland in early May.

Caritoux was helping out the workers in his family vineyard in Provence just two days prior to the start of the 1984 Vuelta when he received a call from de Gribaldy. (Wilcockson, 1984). International cycling at this time, particularly in Spain, was not nearly as well-organized as it is today. De Gribaldy had heard nothing from the Spanish organizers of the Vuelta for weeks and assumed that the team’s proposed candidacy in the race had been cancelled. (Wilcockson, 1984). This was not the case, however, and he was threatened with a $50,000 fine if he didn’t get a team to the start line! The Skil riders not helping Kelly in the April Classics were needed at the Vuelta! Caritoux, on vacation no more, got himself to Geneva as quickly as possible to catch a plane for the South of Spain!

Little was expected of the hastily assembled Skil team in terms of results, and de Gribaldy sent an assistant to guide them as he was with Kelly in Belgium and France for the classics. The French team was largely ignored in the build-up to the race as a confrontation was predicted between Italian superstars Giuseppe Saronni and Francesco Moser and the strong Spanish contingent: Tour de France runner-up Angel Arroyo, 1983 Vuelta winner Pedro Delgado, Alberto Fernandez (3rd in both the 1983 Vuelta and Giro), Julian Gorospe, and 1982 Vuelta winner Marino Lejarreta. Caritoux told Winning Magazine, after holding the King of the Mountains jersey for most of Pays Basque that “I realized I was the equal to the Spaniards in the mountains, and I thought I would be able to finish in the top 10 of the Vuelta” (Wilcockson, 1984).

The 19 stage 3385 km event ran from April 17-May 5 and featured many interesting plots. Milan-San Remo winner and Hour Record Holder Francesco Moser convincingly won the prologue and led for the first six days. He was preparing for the Giro (which he would win) scheduled to begin just twelve days later. The Belgians dominated the field sprints of the opening week with Noël Dejonckheere (well known to American fans from the criteriums of the Coors Classic in Colorado) and Jozef Lieckens taking two apiece. Their compatriot Guido Van Calster of the Italian Del Tongo team won the other and his consistency throughout the Vuelta’s sprints (seven times on the podium) would ultimately earn him the points title. Stage six was won by another Belgian, the veteran Michel Pollentier, from a breakaway, before the race headed into the mountains.

Stage seven would finish atop Rasos de Peguera in the Spanish Pyrenees. Caritoux dropped Spaniard Fernandez and Colombians Edgar Corredor and José Patrocinio Jiménez (winner of the 1982 Coors Classic) to win the stage sixteen seconds clear of Delgado. Delgado took over the Amarillo (light yellow, not red like today) jersey of race leadership with Fernandez three seconds back and Caritoux in third. Overnight leader Moser was left six minutes adrift. Thrilled to win a stage, Caritoux still hoped for top ten but worried about his time trialing and lack of team support in the mountains against the combined might of the Colombians and Spaniards.

Another Belgian veteran, Classics legend Roger De Vlaeminck triumphed on stage eight into Zaragoza, while stages nine and ten were breakaway wins for Italians Orlando Maini and Palmiro Masciarelli, all with no change to the overall standings. Moser won another mass gallop into Santander on stage eleven with the queen stage to Lagos de Covadonga looming ahead for Stage 12.

Delgado, the defending champion who would eventually finish fourth still held the overall lead. Attacks were anticipated from Colombians Corredor and “Patro” Jiménez, but they never came. Instead, it was the surprising Caritoux, who launched 7 km from the rocky summit with only German Reimund Dietzen and Fernandez able to latch on. Fernandez proceeded to then attack no fewer than four times, but his two companions were always able to close the gap. Dietzen won the sprint for the stage, but the young Frenchman took the leaders jersey by 32 seconds over Fernandez. The following day was another field sprint and yet another stage win for the Belgians: this time Van Calster. The Stage 14 time trial, a 12-kilometer climb from Lugones to Monte Naranco, was handily won by Gorospe. The surprising Caritoux was second at 40 seconds, with Fernandez a further five seconds behind. The vine cutter not only kept his overall lead but increased it to 37 seconds.

According to Winning magazine, “the young Frenchman had to survive a whole barrage of abuse from the tightly packed, almost hysterical Spanish public. People spat at him as he passed, sprayed water into his face and hurled rolled-up newspapers at him. Hinault had withstood similar treatment in 1983, when stones were also among the missiles thrown at the unwelcome ‘foreign’ race leader (Wilcockson, 1984). Fernandez, reportedly played the role of gentleman peacemaker, publicly complimenting his rival but things only simmered down temporarily.

Spaniard Antonio Coll took a breakaway win on an innocuous stage 15 into Leon to soothe the host nation and yet another Belgian, Daniel Rossel, triumphed in a similar way into Valladolid the following day. The 258-kilometer Stage 17 featured four mountain passes and Caritoux reportedly made an agreement with Fernandez to help control the attacks of Reynolds teammates Gorospe and Delgado. It seemed to work to maintain the status quo, turning the stage into a seven-and-a-half-hour slog through rain and snow, which was won solo by José Recio with all the favorites finishing together. The only things remaining between Caritoux and final victory were a short morning road stage, a decisive afternoon time trial, and the celebratory finale into Madrid.

The morning stage changed nothing. Everything rested on the 33-kilometer test in Torrejón de Ardoz. Caritoux told Winning Magazine “I’m inclined to make Fernandez the favorite, I think he has a 60% chance of winning this Vuelta” (Wilcockson, 1984). The interim Skil manager requested two motorcycle police escorts to accompany the race leader through the massive crowds that gathered on the roadside. It was a dramatic conclusion to the Spanish Grand Tour with the partisan crowd roaring on their favorite Fernandez and Caritoux enduring something entirely different behind. “Caritoux was trying to make the most of his overly upright style and pedaling an unnaturally high gear through another barrage of paper balls and abuse” (Wilcockson, 1984). It was even reported that the Frenchman had to repeatedly swerve to avoid tall weeds that some spectators threw towards his sprockets! At half-distance, he appeared defeated having lost over half his leading margin.

When the dust had settled, Gorospe had won the tumultuous stage, again with a large margin, and Fernandez was fifth 54 seconds in arrears. And the besieged vacationer from France? He rallied to finish ninth,1:25 behind, thus preserving a precious six-second cushion! The final day’s promenade into Madrid would change nothing as Dejonckheere joyously pipped Van Calster in the bunch gallop. A humble Fernandez, who sadly would die in a car crash later that year, raised his foreign rival’s arm on the podium in triumph to silence the Spanish crowd. Caritoux, however, did not get to return to his well-earned rest in the vineyards as de Gribaldy had another plane waiting in the airport to whisk him off to Switzerland for the Tour of Romandie, which began the very next day!

- Merckx, E. & Michaux, L. (1984) “Season 1984: The Fabulous World of Cycling”. Brussels, Belgium: Winning Bicycle Racing Illustrated.

- Wilcockson, J. (1984, August). “Spanish Eldorado for Caritoux: The young Frenchman is the surprise winner of the Vuelta a España”. Winning Bicycle Racing Illustrated, Number 13, pages 72-75.