The 1975 Tour de France and the end of cycling’s most ruthless dynasty

By Steven L. Sheffield — In the summer of 1975, somewhere on a melting ribbon of Alpine asphalt four kilometers from the ski station of Pra-Loup, the most dominant athlete of his generation began to die a very public death. Behind Eddy Merckx, gaining with each pedal stroke, came a quiet Frenchman whose very existence seemed to violate the natural order of professional cycling.

The moment Bernard Thévenet passed the faltering Belgian that July afternoon represented more than a changing of the guard in sport’s most grueling theater. It was the collapse of an empire built on the simple, terrifying premise that one man could be so superior to his peers that competition became mere formality. For five of the previous six years from 1969 to 1974, Merckx had treated the Tour de France not as a race but as a harvest, methodically consuming everything in his path: stages, jerseys, records, and most devastatingly, hope itself. The one year he didn’t (1973), he skipped the Tour de France in favor of racing the Vuelta a España and Giro d’Italia, winning both.

But empires, even sporting ones, carry within them the seeds of their own destruction. In 1975, that destruction would come in the most unlikely of forms: not through tactical miscalculation or mechanical failure, but through the accumulated weight of expectation, the fist of a spectator, and the patient ambition of a dreamer from a village called The Handlebar.

Le Guidon

Bernard Thévenet was born in Le Guidon—literally “The Handlebar”—a hamlet so small it seemed more prophecy than place. If destiny has a sense of humor, it revealed itself in that name, in the cosmic joke of a future Tour winner emerging from a village that shared its moniker with an essential component of a bicycle.

Thévenet’s cycling epiphany arrived in church. The year was 1961, and young Bernard was serving as a choirboy when the priest made an unusual announcement: Mass would begin early so the congregation could watch the Tour de France pass through their region. When the peloton finally swept by in a blur of chrome and color, something fundamental shifted in the boy’s understanding of what was possible.

“The sun was shining on their toe-clips and the chrome on their forks,” he remembered years later. “I had already been dreaming of becoming a racing cyclist and that magical sight convinced me definitively.”

It was a vision sustained through grinding years of amateur racing and the skepticism of farming parents who needed their son’s labor more than his dreams. Thévenet rode his sister’s bicycle to school from age six, graduated to his own bike a year later, and began the daily ten-kilometer pilgrimage that would prepare his legs for mountains he had never seen.

When his parents discovered his first race only through the local newspaper, there was “a row”—but Thévenet won that race, and victory, as it so often does, silenced all objections. By 1975, this son of the soil had transformed himself into something his childhood vision could never have imagined: not a knight in shining armor, but a patient assassin of cycling royalty.

The Hollow Crown

To understand Thévenet’s eventual triumph, one must first grasp the psychological prison that Merckx’s success had constructed around him. By 1975, the Belgian had become a victim of his own dominance, trapped by expectations that had calcified into inevitability. The man they called “The Cannibal” for his insatiable appetite for victory had begun to find that even cannibals could lose their hunger.

Merckx’s spring campaign that year had been devastating in its completeness. Wearing the rainbow jersey, he won Milan-San Remo, the Amstel Gold Race, the Tour of Flanders, and Liège-Bastogne-Liège, among others. Each victory, however, felt less like triumph than obligation. The joy had leached out of racing, replaced by the grim duty of maintaining an empire that everyone, including Merckx himself, secretly understood could not last forever.

The first cracks appeared not on the bike but in bed. Merckx contracted a cold and, later, tonsillitis during his spring campaign, causing him to skip the Giro d’Italia for the first time in years. For a man whose legend rested on racing everything, everywhere, the decision represented seismic shift.

Meanwhile, Thévenet was gathering quiet confidence. On June 9th, he won the Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré while Merckx finished a distant tenth. It was the kind of result that, in any other era, would have been dismissed as anomaly. But in 1975, with Merckx showing signs of mortality, it felt like permission to dream.

“In the end, perhaps there was a possibility,” Thévenet reflected years later. “I knew I couldn’t let it slip away.” That single word—”perhaps”—contains multitudes. It acknowledges the audacity of challenging the unchallengeable while maintaining the humble realism that would prove essential to his success.

The Peloton Assembled

When the 1975 Tour de France began in Charleroi on June 26th, the early stages revealed both familiar patterns of Merckx’s control and subtle signs of disruption. On the second day, Thévenet lost nearly a minute—a gap that would have been fatal in previous Tours when Merckx’s form was unassailable.

“That morning, between Charleroi and Molenbeek, I lost almost a minute, it started badly,” he recalled. “But in the afternoon the race exploded, and I managed to hold on and follow the leading group. I was just happy to still be in the game!”

This Tour felt different from the start, charged with electricity that suggested the established order might be more fragile than it appeared. Merckx continued to demonstrate his superiority in time trials, winning two stages against the clock and maintaining his yellow jersey. But Thévenet was not being distanced as expected. In the crucial time trial into Auch, he lost only nine seconds—a result that left him tantalizingly close at 2’20” behind.

The psychological warfare had begun. “During the rest day, Merckx said I was his main rival,” Thévenet recalled. In that acknowledgment lay both threat and opportunity. For the first time in years, the Belgian would have to hunt specific prey.

The First Crack

Professional cycling reserves its most revealing moments for the mountains, those cathedrals of suffering where pretense dissolves and truth emerges in its rawest form. When the 1975 Tour reached the Pyrenees, the real battle began.

On July 8th, the Tour reached Pau for Stage 11, the first major test in the mountains. The stage would prove to be a seismic shift disguised as routine mountain theater, the moment when whispers of Merckx’s mortality crystallized into observable reality. What transpired in those ancient peaks would not topple the king immediately, but it would reveal the first hairline fractures in what had seemed an impenetrable fortress.

The stage began with the familiar choreography of mountain racing—early attacks, calculated pursuits, the gradual winnowing of the peloton as the road tilted skyward. But as the kilometers accumulated and the gradient bit deeper, something unprecedented began to unfold. Bernard Thévenet and Joop Zoetemelk, the taciturn Dutchman who had spent years in Merckx’s shadow, found themselves riding away from the very man who had made such escapes impossible for half a decade.

For those who witnessed it, the moment carried the surreal quality of watching natural law reverse itself. Merckx, the eternal predator, suddenly appeared as prey. The Belgian, who had built his legend on the simple premise that no one could sustain a pace he could not match, found himself watching two riders disappear up the mountain while his own legs, for the first time in memory, refused to respond to his will.

Zoetemelk would claim the stage victory, his first taste of what it meant to beat the unbeatable. He crossed the line with the measured satisfaction of a man who had waited years for such a moment, knowing that behind him, Thévenet followed just six seconds later. But the real drama played out nearly a minute further back, where Merckx arrived with the hollow-eyed expression of someone who had glimpsed his own mortality.

The time gaps alone—fifty-five seconds to Zoetemelk, forty-nine to Thévenet—might have been dismissed as tactical miscalculation in any other era. But this was 1975, and such margins represented something more ominous: the first public acknowledgment that the Cannibal’s appetite was no longer infinite. The stage had reduced the contenders to their essential elements: Thévenet, Zoetemelk, Lucien Van Impe, and Merckx. Everyone else had been relegated to the role of spectator in what was shaping up to be cycling’s most consequential drama.

In the press room that evening, journalists who had spent years chronicling Merckx’s dominance found themselves grappling with an unfamiliar narrative. Here was the man who had devoured everything in his path, suddenly looking vulnerable on the very terrain where his supremacy had seemed most absolute. The questions came carefully, respectfully, but with an undercurrent of anticipation that would have been unthinkable just days earlier.

Merckx himself understood the significance of what had occurred. In the measured tones of a general acknowledging his first tactical defeat, he spoke of the difficulty of the stage, the strength of his rivals, the long road still ahead. But those who knew him best could detect something new in his voice: not quite doubt, but the absence of the absolute certainty that had characterized his previous campaigns.

For Thévenet, the stage represented vindication of his quiet confidence. He had not merely survived in the mountains; he had thrived, demonstrating that the legs forged in the hills around Le Guidon could indeed carry him to places where even Merckx could not follow. The farmer’s son had served notice that the empire’s borders were no longer secure, that the unthinkable was slowly becoming inevitable. “I could have gained more, I punctured near the finish,” Thévenet explained with the casual confidence of a man who had begun to believe in his own superiority.

The Pyrenean stage would be remembered not for its drama—there had been little of the fireworks that would later characterize Pra-Loup—but for its revelation. Like the first crack in a great dam, it appeared insignificant to casual observers but contained within it the promise of the flood to come. In the mountains above Pau, the natural order of professional cycling had shifted, almost imperceptibly, but definitively. The Cannibal had shown his first sign of satiation, and in a sport where vulnerability is measured in seconds, fifty-five seconds might as well have been eternity.

Puy-de-Dôme

The cracks that had first appeared in the Pyrenees were widening with each mountain stage. What had begun as whispers of vulnerability in Stage 11 had grown into audible murmurs of possibility. Merckx, sensing the shift in the peloton’s psychology, began to race with the desperate intensity of a man who understood that his empire was under siege. But desperation, in professional cycling, often breeds the very mistakes it seeks to avoid.

Three days later came the stage that would shatter Merckx’s aura of invincibility in the most brutal and unexpected way. The climb to Puy-de-Dôme had always been a crucible of the Tour, its volcanic slopes a fitting metaphor for the explosive tensions that mountain stages invariably unleash. But on July 11, 1975, it became something more: the site of cycling’s most infamous assault, a moment when the sport’s unwritten contract between athlete and audience was torn asunder by the very passions that make cycling France’s most visceral spectacle.

The stage had begun with the familiar rhythms of mountain warfare. Early attacks were absorbed, the peloton stretched and compressed like an accordion as the gradient fluctuated, and gradually the pretenders fell away until only the true contenders remained. Thévenet, riding with the measured confidence of a man who had discovered his own strength, positioned himself perfectly for the final assault. Behind him, Merckx rode with the grim determination of a champion who sensed that his reign was entering its final act.

As the riders approached the summit, the crowds thickened into a human corridor of noise and emotion. French spectators, intoxicated by the possibility of witnessing their countryman humble the Belgian colossus, pressed against the barriers with an intensity that bordered on hysteria. In such moments, the line between passionate support and dangerous obsession can become dangerously thin.

The attack, when it came, was swift and devastating. As Merckx prepared for the final sprint to the line, disaster struck from the crowd itself. First, a woman leaned over the barriers and slapped him—a shocking breach of the respect traditionally accorded to cycling’s greatest champions. Then, inside the final kilometer, came an assault that would be remembered as one of sport’s most cowardly acts: a French spectator named Nello Breton, driven by his devotion to Jacques Anquetil and his inability to bear watching his idol’s record fall to a Belgian, punched the champion in the kidneys with the force of accumulated resentment.

The assault was more than physical violence; it was a violation of the unwritten contract between athlete and audience, a reminder that even the greatest champions remain vulnerable to the basest human impulses. But it was also something more insidious: a manifestation of the pressures that had been building around Merckx for years, the weight of being simultaneously the most admired and most resented athlete in his sport.

Merckx, his face contorted with pain and shock, somehow managed to cross the line thirty-four seconds behind Thévenet. The margin might have been manageable under normal circumstances, but these were no longer normal circumstances. The Belgian immediately vomited, his body finally succumbing to the accumulation of stress, illness, and violence. The image of cycling’s greatest champion, doubled over in agony while his rival celebrated, would become one of the sport’s most haunting tableaux.

During the rest day that followed, team doctors discovered that Merckx was suffering from an inflamed liver—a condition that may have been exacerbated by the punch but was likely the result of months of accumulated stress and the lingering effects of his spring illnesses. He was prescribed pain medication and blood thinners, treatments that may have further contributed to his weakened state. The irony was cruel: the man who had built his legend on his ability to suffer more than any other rider was now suffering in ways that actually diminished his capacity to compete.

For the first time in his career, opponents sensed genuine weakness in their tormentor, and like sharks detecting blood in the water, they began to circle. The psychological shift was palpable. Where once riders had resigned themselves to racing for second place, they now began to believe that the ultimate prize might actually be within reach. The emperor’s clothes were not merely threadbare; they were falling away entirely, and everyone could see it.

Pra-Loup

July 13, 1975. Stage 15: Nice to Pra-Loup. Despite everything that had transpired—the early cracks in the Pyrenees, the humiliation at Puy-de-Dôme, the mounting evidence of his mortality—Merckx still led the Tour de France by 58 seconds. It was a lead that, in any other year of his dominance, would have been insurmountable. But 1975 was not any other year, and the man who had once made such margins feel like eternities now found himself defending a gap that seemed to shrink with each labored breath.

One mountain stage separated him from what would have been his sixth Tour de France victory and an unprecedented place in cycling history. The mathematics were simple: survive the Alpine crucible of Pra-Loup, and the Tour would be his. But mathematics, as Merckx was about to discover, mean nothing when the body begins its rebellion against the will.

The stage began in Nice under a merciless Provençal sun, the kind of heat that transforms tarmac into rivers of melting tar and reduces the strongest riders to mere mortals. For the thousands of spectators who had made the pilgrimage to witness what many expected to be Merckx’s triumphant defense of his crown, the day promised to be a celebration of cycling’s greatest champion. Instead, they would witness one of sport’s most dramatic collapses, a fall from grace so complete and public that it would redefine what it meant to be vulnerable in the face of greatness.

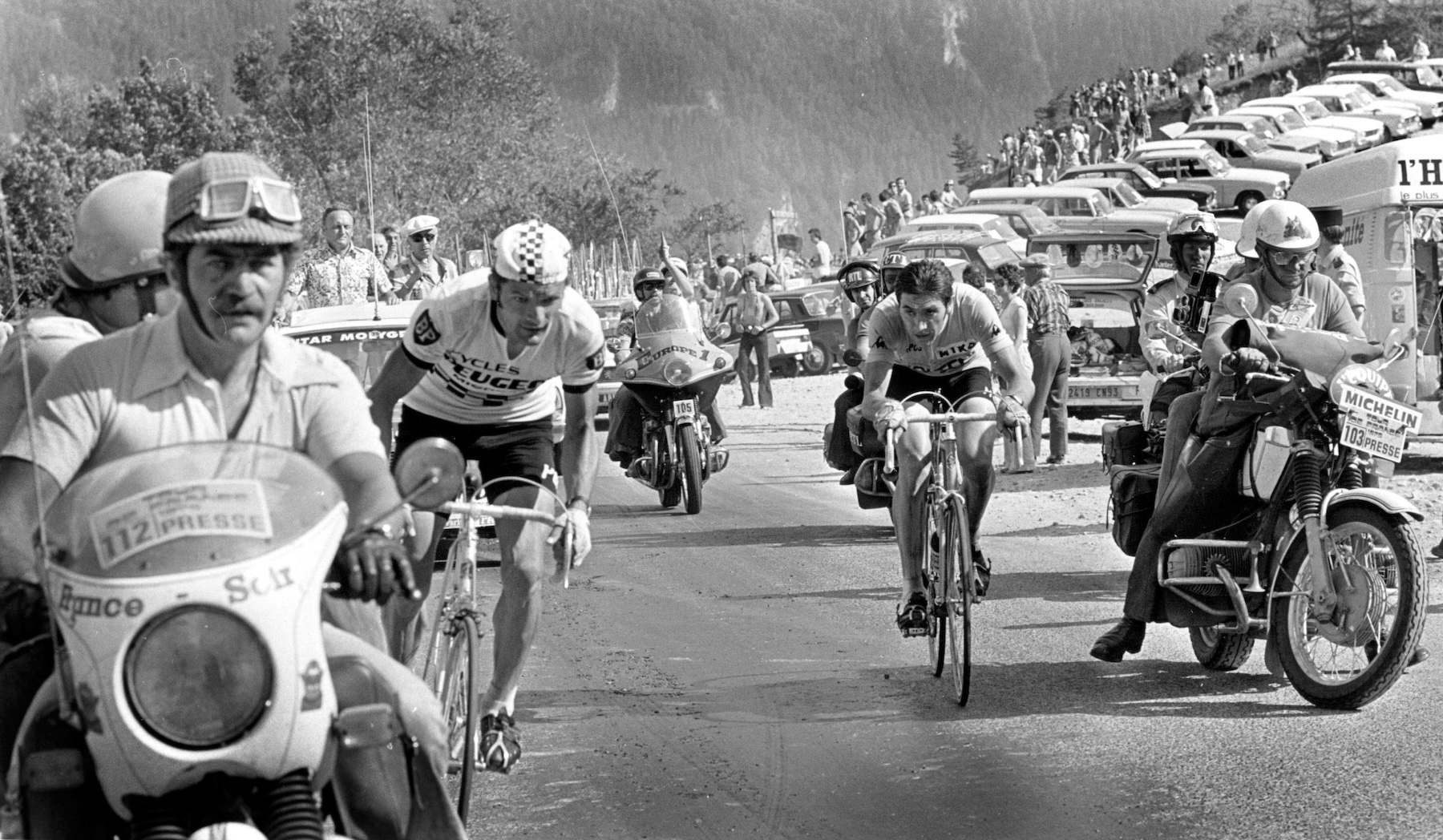

What unfolded on that scorching Alpine afternoon has been preserved in the collective memory of cycling as one of sport’s most epic battles. Pierre Chany, L’Équipe’s legendary correspondent, captured the drama with the lyrical precision that only comes from witnessing history: “Those who were there will be slow to forget Bernard Thévenet’s six successive attacks in the never-ending climb of the Col des Champs, Eddy Merckx’s immediate and superb response, the alarming chase by the Frenchman after a puncture delayed him on the descent…”

The battle began on the Col des Champs, where Thévenet launched attack after attack with the methodical precision of a master craftsman. Each assault was answered by Merckx’s superior tactical intelligence, the Belgian drawing upon decades of experience to neutralize threats that would have destroyed lesser champions. For those watching from roadside, it appeared to be another chapter in the familiar story of Merckx’s inexorable march to victory.

On the descent, the Belgian even gained ground, his technical skills allowing him to claw back precious seconds while Thévenet struggled with a puncture that threatened to derail his entire campaign. The moment perfectly encapsulated the cruel mathematics of professional cycling: all the fitness in the world means nothing when fortune turns against you. But Thévenet, displaying the tenacity that had carried him from the farms of Le Guidon to the pinnacle of professional cycling, refused to surrender to circumstance.

As the race approached the Col d’Allos, Merckx appeared to be in his element. His Molteni teammates set a blistering pace, distancing themselves from competitors before the final climb. The Belgian rode with the measured confidence of a man who had orchestrated such scenarios countless times before. For thousands of spectators lining the roadside, it looked like another chapter in the familiar story of his inexorable march to victory.

But then, four kilometers from the summit of Pra-Loup, the unthinkable happened: Eddy Merckx simply stopped being superior.

The collapse, when it came, was total and public, a disintegration so complete that it seemed to violate the fundamental laws of professional cycling. The man who had built his legend on never showing weakness suddenly became weakness incarnate, his body betraying him in the most visible way possible. The heat, the accumulated stress, the lingering effects of illness and assault—all of it converged in a moment of pure, undeniable human limitation.

British writer Graeme Fife would later paint an unforgettable portrait of that moment: “Thévenet caught Merckx, by now almost delirious, 3 km from the finish and rode by. The pictures show Merckx’s face torn with anguish, eyes hollow, body slumped, arms locked shut on the bars, shoulders a clenched ridge of exertion and distress. Thévenet, mouth gaping to gulp more oxygen, looks pretty well at the limit, too, but his effort is gaining; he’s out of the saddle, eyes fixed on the road. He said he could see that one side of the road had turned to liquid tar in the baking heat and Merckx was tire-deep in it.”

The metaphor was perfect: the great Merckx, trapped in melting asphalt, watching helplessly as his era dissolved beneath him while his conqueror rode past into history. The road itself seemed to be rebelling against the old order, creating a physical manifestation of the psychological quicksand that had been slowly consuming the Belgian champion.

For those who witnessed it, the moment carried a weight that transcended sport. Here was the man who had redefined what it meant to be dominant, reduced to a figure of almost Shakespearean tragedy. The crowds who had come to witness his triumph instead found themselves watching the public execution of a dynasty, the end of an era that had seemed as permanent as the mountains themselves.

As Thévenet disappeared up the mountain, his climbing style pure and economical while Merckx’s became increasingly labored and desperate. The stage finished with Thévenet claiming a victory that was both personal triumph and historical watershed. Behind him, Merckx arrived looking like a man who had aged years in the space of hours, his face bearing the hollow expression of someone who had glimpsed his own mortality and found it wanting.

When Bernard Thévenet crossed the finish line at Pra-Loup, he had achieved something that transcended sport: he had proven that even the most complete dominance contains within it the possibility of its own ending. Merckx finished fifth, one minute and twenty-six seconds down, and lost the yellow jersey that had seemed permanently affixed to his shoulders to the farmer’s son who had dared to dream of the impossible.

In the press conference that followed, the questions came with the careful reverence reserved for witnessing the end of an era. Thévenet, exhausted but gracious, spoke of his satisfaction at finally fulfilling his childhood dreams. Merckx, displaying the dignity that had always characterized his career, offered congratulations to his conqueror while privately grappling with the reality that his empire had crumbled in the space of a single Alpine afternoon.

The following day, Stage 16—just 107 kilometers from Barcelonnette to Serre Chevalier—was short in distance but operatic in scope. It played out not merely as a mountain stage, but as a passing of the torch, a subtle tragedy unfolding beneath the jagged spires of the Alps. The route coiled upward over the Col de Vars and then the stony, lunar flanks of the Col d’Izoard, a climb soaked in Tour legend and freighted with the ghosts of Coppi and Bobet. It was here that Bernard Thévenet, compact and composed, rose out of the saddle and into a different echelon of cycling history.

As Thévenet danced upward in the thinning air on the Col d’Izoard, Merckx faltered behind again, riding not just against his rival but against the erosion of inevitability. By the time Thévenet descended into Serre Chevalier, greeted by a delirious crowd and the high-altitude hush of a July afternoon, Thévenet had dealt the final blow to Merckx’s domination.

A bikini-clad spectator by the roadside held up a sign that would become as famous as the moment itself: “Merckx is beaten. The Bastille has fallen.” It was Bastille Day in France, and the symbolism could not have been more perfect. The cycling monarchy had been overthrown not by revolution but by the simple, inexorable process of human limitation asserting itself over human ambition.

For Merckx, there would be no miraculous recovery. Though he would later crash and break a cheekbone—gaining back some time through the sympathy and tactical confusion that injuries create—the damage was irreversible. Team doctors advised him to abandon the race, but Merckx, displaying the stubborn pride that had made him great, refused to quit.

Champs-Élysées

When the 1975 Tour de France reached its historic first finish on the Champs-Élysées, the transformation was complete. Thévenet concluded his efforts with a time of 114h35’31”, winning by 2’47” over Merckx, with Lucien Van Impe third. It was the first time Merckx had lost a Tour in his six starts, and it would be his final podium appearance in cycling’s greatest race.

Years later, reflecting on his defeat with the wisdom that comes only from having experienced both triumph’s heights and loss’s depths, Merckx displayed characteristic grace: “For years, people have been waiting for me to collapse. But the collapse never came. To be beaten, I had to come up against someone stronger than me.”

It was a generous assessment, though perhaps not entirely accurate. Thévenet had not been stronger than peak Merckx; he had been stronger than diminished Merckx—Merckx the victim of his own success, Merckx the prisoner of expectations that had grown beyond any human’s capacity to fulfill. In cycling, as in all sports, timing is everything, and Thévenet’s greatest gift may have been his exquisite sense of when the moment had arrived to strike.

After

Bernard Thévenet would win the Tour de France again in 1977, but he would always be remembered first as the man who proved that even cannibals could be fed their last meal. His victory represented something more profound than a changing of the guard; it restored to cycling the possibility of surprise, the understanding that no matter how complete a dominance might appear, sport retains its capacity to humble even the mightiest.

Within three years of his defeat, Merckx would retire from professional cycling, psychologically exhausted by the burden of being perpetually hunted. “I was psychologically exhausted,” he admitted. “I always wanted to win, I couldn’t anymore. I became aware that they were surrounding me like a wounded lion.” The hunter had indeed become the hunted, and like all great predators, he understood when it was time to leave the field to younger, hungrier competitors.

Looking back on his childhood vision of cyclists as heroes, Thévenet offered a reflection that captures both the romance and reality of athletic achievement: “They were modern-day knights,” he said of that moment when the peloton swept past his village church. “It was never that magical when I was actually in the peloton of the Tour!” The observation contains multitudes—the gap between dreams and reality, the way proximity diminishes mystery, the understanding that heroes are ultimately just human beings pushed to their absolute limits.

Yet for one glorious moment on the road to Pra-Loup, magic had indeed occurred. A dreamer from a hamlet called The Handlebar had proven that even the greatest champions are mortal, that every reign must eventually end, and that in cycling, as in all great narratives, there is always room for one more miracle.

The year 1975 would leave lasting marks on the Tour de France—the polka-dot jersey for the best climber, the white jersey for the best young rider, the historic finish on the Champs-Élysées—but perhaps its greatest gift to cycling history was simpler and more profound: it reminded the world that the most beautiful stories are not about dominance but about the courage to challenge the unchallengeable, the wisdom to recognize when the moment has arrived, and the grace to understand that every ending creates space for a new beginning.

In the end, Thévenet’s triumph was about the eternal human capacity to dream beyond the boundaries of the possible, to persist in the face of overwhelming odds, and to recognize that sometimes the smallest person in the room possesses the power to topple giants. On that sweltering afternoon high in the French Alps, a son of the soil proved that even the most ravenous appetites must eventually be satisfied, not by victory, but by the simple, inexorable fact of human limitation. In serving that final meal on melting tarmac, he reminded the world that in sport, as in life, every feast must eventually come to an end.

Sources

The information in this article is drawn from the following sources:

- Belbin, Giles.“How Bernard Thévenet Dethroned Eddy Merckx at the 1975 Tour.” Cyclist Magazine, April 2001. https://www.cyclist.co.uk/in-depth/how-bernard-thevenet-dethroned-eddy-merckx-at-the-1975-tour.

- Chany, Pierre. L’Équipe (via Wikipedia).

- Cycle Sport, May 2000 (via Wikipedia).

- Fife, Graeme. Tour de France: The History, the Legend, the Riders. Mainstream Press, 1999.

- Fotheringham, William. Half Man, Half Bike: The Life of Eddy Merckx, Cycling’s Greatest Champion. Chicago Review Press, 2013.

- Friebe, Daniel. Eddy Merckx: The Cannibal. Ebury Press, 2012.

- Kaloc, Jiri. “The Fall of Eddy Merckx, One of the Greatest Tour de France Champions.” Skoda: We Love Cycling. https://www.welovecycling.com/wide/2021/06/30/the-fall-of-eddy-merckx-the-greatest-tour-de-france-champion/

- McGrath, Andy. “Eight Pivotal Moments in the Career of Eddy Merckx.” Rouleur Magazine. https://www.rouleur.cc/en-us/blogs/the-rouleur-journal/eight-pivotal-moments-in-the-career-of-eddy-merckx.

- Official Tour de France. “A Landmark Year IV/IV: Thévenet Devours the Cannibal.” https://www.letour.fr/en/news/2025/1975-a-landmark-year-iv-iv-thevenet-devours-the-cannibal/1324936.

- Velo101. “Tour de France 1975: Il Était Une Fois Pra-Loup.” (translated by Google) https://www.velo101.com/courses/tour-de-france/tour-de-france-1975-il-etait-une-fois-pra-loup/.

- Wikipedia. “Bernard Thévenet.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernard_Thévenet.

- Wikipedia. “Eddy Merckx.”https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eddy_Merckx.

- Wikipedia. “1975 Tour de France.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1975_Tour_de_France.

- Windsor, Richard. “Eddy Merckx and the 1975 Tour de France.” Cycling Weekly, June 2015. https://www.cyclingweekly.com/news/latest-news/eddy-merckx-magic-moment-1975-tour-de-france-59812.