On the evening of Saturday June 28, 1969, a young Belgian cyclist just 24 years of age, dressed in the white and red colors of the Faema squad and wearing dossard #51, took his place on the start-line of the 56th Tour de France in the northern town of Roubaix on the border between France and Belgium; his first appearance. He would not win the Prologue time-trial that day, finishing second to Rudi Altig of the Salvarani team.

22 days later, on Sunday July 20, 1969, Edouard Louis Joseph Merckx—commonly known as “Eddy”—would step onto the top step of the final podium in Paris as the General Classification winner of the Tour de France in his first attempt, wearing the maillot jaune for a total of 19 of those days and winning 6 individual stages in the process, as well as being part of the Stage 1b team time trial winning squad.

Merckx would also finish in Paris as the winner of the Points Classification, the King of the Mountains Classification, the Combination Classification and the overall Combativity Prize. This was the first and only time that a single rider won all of the major classifications at the Tour de France. If it had been an official classification at the time, he would have also won the Best Young Rider award for those riders under the age of 26.

Fifty years later, Merckx’s Tour de France record is well-known, becoming the second rider to win the Tour a total of 5 times—a feat which had only been accomplished by Jacques Anquetil prior to Merckx’s career—collecting a total of 34 stage wins and wearing the maillot jaune a total of 96 days in the process, both of which are records which have yet to be broken. He also amassed 5 wins in the Giro d’Italia and 1 win in the Vuelta, giving him 11 total victories in the Grand Tours, another record which has yet to be broken.

And yet, Merckx almost didn’t start the Tour that late June evening in 1969, and who knows what his career would have looked like had he not.

In 1967, while riding for the Peugeot-BP-Michelin squad, Merckx raced in the Giro d’Italia, finishing 9th overall, with two stage wins.

Later that summer, his Peugeot teammate Tom Simpson died on Mont Ventoux at the 1967 Tour de France, due to heat exhaustion exacerbated by amphetamines and alcohol. While Merckx was not at that Tour, when the news flashed across his television set during the evening news, Merckx became distraught. Simpson had been a friend and mentor to the young Belgian, unlike the hostility that Merckx had faced from his previous team leader Rik van Looy. He immediately decided to attend the funeral in England, the only rider from the European continent to do so. To this day Merckx is saddened that Simpson’s name is so closely associated with doping, rather than for the Briton’s accomplishments while alive.

After Simpson’s death, the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), which is the governing body of the sport of cycling, implemented mandatory doping controls for the 1968 season. The 1968 Giro d’Italia would be the first major Tour to have regular testing, with results to be announced 15 days after the conclusion of the race.

After switching to the Faema team from Peugeot in the off-season, Merckx won the Giro d’Italia—his first of 11 total Grand Tour victories—taking another 3 stage wins. On June 15, 1968, the Italian Cycling Federation announced that 9 riders returned positive tests during the race. Merckx was not one of the offending riders.

Riders testing positive included Italian stars Felice Gimondi and Gianni Motta, along with Franco Balmamion, Franco Bodrero, Raymond Delise, Peter Abt, Victor van Schil, Mariano Diaz, and Joaquin Galera. Balmamion’s result was thrown out, as the substance he tested positive for had yet to be officially banned.

Gimondi’s ban was overturned on July 15, because he claimed he had just used Reactivan, an over-the-counter stimulant appetite suppressant containing fencamfamine, which has similar properties to amphetamines but at about half the strength. At that time, Reactivan was still in the grey area between legal and illegal drugs. With the exception of Balmamion, all of the riders with positive tests served a ban of at least 30 days.

In 1969, Merckx started the Giro d’Italia as the overwhelming favorite, and by the rest day on May 31, he had won an additional 4 stages and wore the maglia rosa—the pink jersey—as the General Classification leader. Then his world fell apart.

On Sunday June 1, after the 16th stage from Parma to Savona won by Roberto Ballini, Merckx was called to Doping Control as the leader of the race. The following morning, Monday June 2, 1969, it was announced that Merckx’s test came back positive for fencamfamine, the same substance that Gimondi had used in 1968. Giro organizer Vincenzo Torriani was forced to exclude him from the remainder of the race, with no right to appeal.

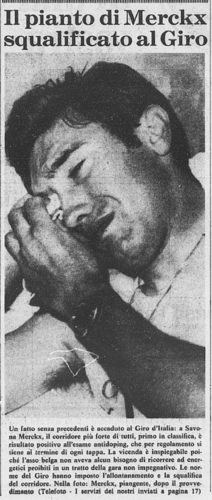

Controversially, the results of the test were announced to the press even before Merckx himself had been informed; the Faema team director Vincenzo Giacotto and Vincenzo Torriani were accompanied by RAI Television crew, along with two reporters—Bruno Raschi from La Gazzetta dello Sport and Théo Mathy, from the Belgian RTBF television.

Immediately after the announcement, Merckx was interviewed by RAI’s Sergio Zavoli in a state of collapse, lying on his bed in Room 11 of the Hotel Excelsior in Albisola Marina, sobbing in French, “I don’t know what to say. I am sure I took nothing. I’m sure of it. I don’t understand anything.” It was the first time that a race leader had been found positive and kicked out of any of the major stage races.

The offense also came with an automatic 30-day suspension, which in this case would not expire until July 2, 4 days after the Tour de France was due to start in Roubaix, meaning he would not be allowed to start. It was a crushing blow. Merckx was convinced that it meant the end of his career, and that he was going to be sacked by his Faema squad.

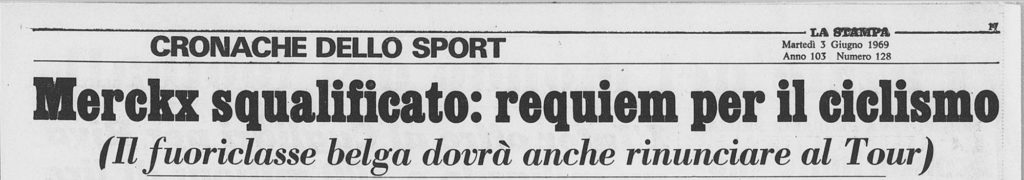

Almost immediately thereafter, Merckx’s supporters began a campaign to have his ban overturned; even much of the Italian media felt that Merckx was the victim of some sort of conspiracy to keep him from winning the Giro d’Italia for a second straight year. The Italian newspaper La Stampa went so far as to call the scandal a “requiem for cycling,” while the headline in the Corriere dello Sport said that “Il ciclismo si sta suicidando (cycling is commiting suicide).” Bruno Raschi’s report for La Gazzetta dello Sport concluded “I can believe that they’ve found Merckx drugged, but I’m sure that someone put the dope in his broth.”

Two days previously, an unnamed support rider on Felice Gimondi’s Salvarani team allegedly knocked on Merckx’s hotel room and offered him a briefcase full of money to throw the Giro, and allow Gimondi to win, which Merckx declined.

Because of this, suspicions were tossed around that Merckx had been intentionally drugged by someone spiking his food or drink with fencamfamine, or that his test samples had been tampered with, in order to get him thrown out of the Giro.

While situations like this seem less plausible in the modern era, in the early days of drug-testing, this was entirely possible. Riders would often accept hand-ups of food or drink from spectators on the side of the road. Teams did not travel with their own chefs or food supplies, and thus had less control over what they ate and drank at meals.

In fact, the entire drug-testing process was still in its infancy; it had been less than two years since Tom Simpson died at the 1967 Tour de France. Despite Simpson’s death, many still questioned whether testing was necessary at all. No real standards had yet to be implemented; not even something as basic as establishing a set list of banned substances, nor guidelines for counter-analysis of B-samples after a positive result.

At the 1969 Giro, testing was done in a mobile lab which followed the race from stage to stage; test equipment was not always well secured and could be knocked out of calibration by jostling and shocks from poor roads. Samples were also not sealed and secured in the same manner as they are today, so it is entirely possible that the samples were indeed tampered with.

Merckx also had the support of the Belgian government, which issued a statement stating the that accusations “were without foundation” and that he was the “sacrificial victim of a criminal plot.” Merckx’s wife Claudine later estimated that her husband received over 10,000 letters of support, which took until the end of the Tour de France to answer them all, after enlisting the help of friends, family, and neighbors.

On June 14, 1969, the Fédération Internationale du Cyclisme Professionnel (FICP), which governed the sport of professional cycling under the auspices of the UCI, convened an extraordinary meeting in Brussels, after which they released a communiqué stating that they:

- Accepted the results of the tests carried out by the Italian doctors

- Granted that the Italian Pro Cycling Union (UICP) had the right to suspend Merckx based on the test results

- Considered the “irreproachable record of the incriminated rider” and the negative results of tests that he had undergone in the past

- Doubted that Merckx voluntarily intended to dope, and

- Gave him the “bénéfice du doute” or “benefit of the doubt” and lifted his sanctions effective immediately.

This meant that Merckx would indeed be able to start the Tour de France just 2 weeks later, but also triggered many protests that he was being given preferential treatment because he was Eddy Merckx, not because he was innocent. At the Tour of Luxembourg, riders staged a mini-strike to express their discontent. 1968 Tour de France winner Jan Janssen declared that “the decision was an injustice towards … lots of little riders who were punished without being able to defend themselves.”

Merckx was also not entirely happy about the wording of the communiqué, as he felt that those 3 words (“bénéfice du doute”) were vague. They didn’t establish guilt or innocence, which meant that Merckx would always have that positive test hanging over his head.

Walter Godefroot, one of Merckx’s friends and rivals on the Flandria squad, knew that Merckx was never more dangerous than when he was down. “When everyone else is hurting, they slow down. When Merckx is in trouble, he attacks,” says Godefroot and so it was.

Merckx had been deeply wounded by the scandal and by the controversy surrounding its outcome, and threw himself into training over the next 14 days after being cleared to race; even riding à bloc for 40 kilometers on the morning of the Tour prologue, tranquille for another 40 kilometers in the afternoon, and then preparing for the prologue time trial that evening in Roubaix.

Merckx was always a prolific winner, but before the Savona affair, he raced with joy. He loved being on the bike, and he loved winning. But afterwards, Merckx lost his innocence and trust in people and the system around him. From that point forward, he always raced as if he had something to prove, which in a sense he did. Every time he won a race and was tested for doping, in his mind each negative test was another piece of evidence that he didn’t need to dope in order to win.

It was during the 1969 Tour after one of Merckx’s 6 stage wins, that Brigitte Raymond, the young daughter of Merckx’s former teammate Christian Raymond, asked her father why Merckx always had to win. When the elder Raymond said that it was because Merckx was the best, Brigitte replied, “well, he’s a real cannibal then.” Her father found this amusing and relayed the story to a couple of journalists. The nickname stuck. From 1969 forward, Merckx was known as “The Cannibal”.

The rest is history.

References:

- Brunel, Philippe. Merckx: intime (France: Calmann-Lévy, 2002).

- Fotheringham, William. Half Man, Half Bike: The life of Eddy Merckx, Cycling’s Greatest Champion (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2013).

- Friebe, Daniel. Eddy Merckx: The Cannibal (United Kingdom: Ebury Press, 2012).

- Strouken, Tonny & Maes, Jan. Merckx 69: Celebrating the world’s greatest cyclist in his finest year (United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Sport, 2015).

- Vanwalleghem, Rik. Eddy Merckx: The Greatest Cyclist of the Twentieth Century (Boulder: VeloPress, 1996).