By Lou Melini

David Ward’s excellent review of Slaying The Badger in the July issue of Cycling Utah is a tough act to follow. However I think, no, I know I have just read a book that ranks as one of the all-time best books reviewed in Cycling Utah. That is a bold statement, as I have reviewed some very good books, Catfish and Mandela, The Yellow Jersey and Once Upon a Chariot to name a few. Road To Valor is that good.

If you want history, bike racing, suspense, and an almost too-good-to-be-true hero, read Road to Valor. I could have read the 240 pages in a day if I didn’t have so many responsibilities that interfered with my reading time! But don’t just read the book, read the author’s note, the prologue, and especially the epilogue. The McConnon siblings did an excellent job researching the book with 50 pages of footnotes at the end of the book.

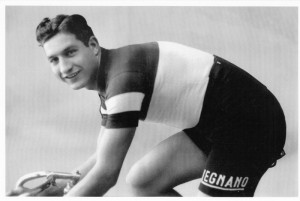

Essentially the book is about the life of Gino Bartali, the winner of 2 editions of Tour de France and 3 of the Giro de Italia. His first tour win was in 1938 and his second in 1948. Unfortunately he had his career interrupted by WWII so Mr. Bartali was denied the ability to be a 5-time (or more) winner as there wasn’t a Tour from 1940-1946 just as he was entering the pinnacle of his career. Born in 1914, he rode his first race in 1931 turning pro four years later.

The book is divided into three sections, Mr. Bartali’s life before, during, and after WWII. Each section is worthy of a small book. In the first section you will read about Gino’s early life including the environment that led to his passion for bike racing and his first Tour win. This section also discusses the influence of the Italian Fascist regime led by Mussolini on his life on and off the bike. For example, he was denied his request to race the 1938 Giro because the government wanted him to focus on the Tour. Mr. Bartali wouldn’t or couldn’t say much about this. He was well aware that Italy’s first and only previous Tour winner Ottavio Bottecchia mysteriously dying in a training ride after “speaking and acting on his political views that were unsympathetic towards Mussolini and the Fascist regime”.

The second section is devoted to Gino’s life during the war. This section is the primary reason for you to read this book. Gino was drafted in the Army but because of his Tour win, he was lucky enough to be assigned as a messenger even being allowed to ride his bike rather than the standard issue motor scooters. He was quite the athletic icon in Italy. When the Allied forces landed in Sicily and took control of Southern Italy, rumors spread that Italy was freed from Fascist control and Gino was discharged from the Army. This turned out to not be true. Most of Italy was now under direct control of the German Army. Gino, however, was “recruited” into a different organization. Being a devout Catholic, Gino became part of group from within the Catholic Church that hid Jews from persecution and death camps. He continued to use his bike as a messenger only this time he carried false documents for the Italian Jewish population. His role was so secret that even his wife was unaware of what he was doing in order to save his family for had he been caught he would have been put to death. In addition he would ride from town to town procuring meager food supplies from a deprived population, carrying the provisions to those more in need.

Gino was “out training” on these missions, many time riding several hundred miles over a few days to deliver his goods. Because of his fame as a cyclist, Gino could fairly easily pass through checkpoints. He even used his fame to distract German and Fascist soldiers at train stations. He would position himself in a café where soldiers would want his autograph. Meanwhile Jews and anti-Fascist Italians hidden on one train could switch to another train without detection. Gino didn’t always fare well and he was once arrested and sent to a well-known torture house. Even there his fame as a cyclist helped as he was released after three days of captivity enabling him to continue his work.

The third section of the book was so too speak the final chapter of Gino’s racing career. His second win in the Tour de France despite a span of 10 years is detailed making him the only tour winner with such a span of time between wins. His rivalry with Fausto Coppi is discussed, also a two-time winner of the Tour. Considered old and washed up by many, Gino went on to win the 1948 Tour despite a 21-minute deficit going into the mountain stages. To help Gino, the post-war elected Prime Minister of Italy called him to offer encouragement and how important his win would be to the Italian people. He then went on to win the stage gaining 20 minutes back. The next day he was called by the Catholic Pope’s secretary, saying the Pope was praying for him to win the race, thus Gino convincingly took the yellow jersey on that stage. That was the power of Gino’s fame.

In between learning about Gino Bartali, you will be treated to numerous small stories and anecdotes throughout the book. These are fascinating tidbits of entertainment and history adding immensely to an already sensational story.

∗ It was well known that famous sports stars including bike racers had many female admirers. Henri Pelissier was so popular with woman that he received dozens of marriage proposals despite being married. He rebuffed these requests by employing his wife to answer the letters. She grew tired of this arrangement and after 10 years of it she took her own life. Pelissier took up with another woman but in the midst of an argument she shot and killed him with the same gun his first wife had used to end her life.

∗ On race days breakfast began with an espresso and some bread with jam or Gino’s favorite: honey. Next he ate pasta or rice with a cheese or butter sauce, ideally accompanied by eggs, veal or steak. For a midday snack, he liked a couple of panini with cheese, marmalade, and salami. During a multiday race, the portions became much larger. In one such race, Gino was eating almost a dozen raw eggs a day while cycling, breaking their shells on his handlebars before swallowing the yolks.

∗ Later in his career, Gino became even more devious in his attempts to sniff out and study the strategies of rivals. He thought nothing of breaking into his opponents’ rooms after they had left for a race to inspect their bathrooms. Most riders had a mix of vials and flasks of various liquids, pills, and powders their trainers recommended. Many were herbal concoctions, placebos that actually did nothing but provide a psychological boost.

∗ Gino stopped by a café’. He left his bike propped against the wall and went inside for a coffee. Something nearby attracted the attention of an Allied plane flying overhead, and it shot a short burst of machine-gun fire in the general direction of the bicycle and the café. Gino was convinced it was the chrome of his bicycle shining in the sun that had drawn the attack. From that moment on, he got in the habit of dirtying up his bike so that it wouldn’t be so reflective. For someone so meticulous about caring for his bike, this felt “sacrilegious”.

∗ For Jews like the Goldenbergs, life had entered a new nightmare phase. The Germans and their Fascist collaborators ratcheted up the intensity of their persecution even as it became increasingly clear that they would be defeated in the war. Their room in the Bartalis’ apartment was evacuated for fear of the increasing frequency of raids. Gino had found them room in the cantina (or cellar) of a building. This space was barely more than ten feet by ten feet, with a low ceiling and stone walls. There were no windows and the one door was always closed. Dark and cold, the room fit one double bed that the four Goldenbergs shared. There was no electricity or running water. Only the mother ever ventured out, armed with a water bucket in each hand. With light brown hair and blue eyes, she did not draw any attention in Florence. The two children (Giorgio and his sister) couldn’t leave, counting flies to relieve the fear and boredom.

The work that Gino and others did during the war was kept a secret until 1978 when a Polish Jewish journalist and filmmaker, Alexander Ramati, published a book about the work of the religious clergy in Assisi during the German occupation, followed seven years later with a film based on the book. Despite this Gino continued to deny his role “as a matter of respect for those who had suffered more than he” and to not “aggrandize his role in the network and overshadow the other participants’ contributions, ordinary Italians and Catholic clergy who took extraordinary risks to save others.” Giorgio Goldenberg left for Israel after the war, never seeing the Bartali family again. However he said when interviewed for this book; “There is no doubt for me that he saved our lives and the lives of hundreds of people. He put his own life and his family’s in danger.”

We hear about the “hardmen” of cycling. You know, those that ride the cobbles of Roubaix, suffer in the heat of the Tour or in the cold and wet of Belgium winters. But all of these riders have nothing on the exploits of Gino Bartali. If you don’t read this book, you will miss on one of the greatest cycling stories ever told.

Road to Valor

By Aili and Andres McConnon

2012

Crown Publishers; a division of Random House.

See also, “My Italian Secret: The Forgotten Heroes”, a film about Gino Bartali.