Giro d’Italia 2026: From Bulgaria to Rome, a Demanding Route with 50,000 Metres of Elevation Gain

ROMA, Italy (1 December 2025) – The 109th edition of the Giro d’Italia, scheduled from 8 to 31 May 2026, promises one of the most demanding courses in recent memory. Covering 3,459 km with 50,000 metres of elevation gain, the race features seven summit finishes, eight flat stages, seven medium-mountain stages, five high-mountain stages, and a 40.2 km individual time trial.

“This year we have designed a more modern Giro, with shorter stages that are no less demanding for the general classification contenders, alternating with stages that will suit riders looking to make an impact with long-range attacks,” said Mauro Vegni, Director of the Giro d’Italia. “There will be seven summit finishes, the same number of stages for the sprinters, and just one individual time trial, although longer than in recent years. I would like to thank everyone who has worked with me and supported me over the years, especially my team and the law enforcement authorities, in particular the traffic police, who have escorted the Giro since its very beginnings.”

The presentation at Rome’s Auditorium Parco della Musica Ennio Morricone was hosted by Pierluigi Pardo and Barbara Pedrotti, with interviews conducted by Paolo Pacchioni of RTL 102.5. Attendees included Simon Yates, Elisa Longo Borghini, and two-time Giro winner Vincenzo Nibali, alongside Italian and Bulgarian authorities, senior RCS executives, and representatives from sport and institutional bodies.

Bulgarian Grande Partenza

The Giro will begin abroad for the 16th time with three stages in Bulgaria.

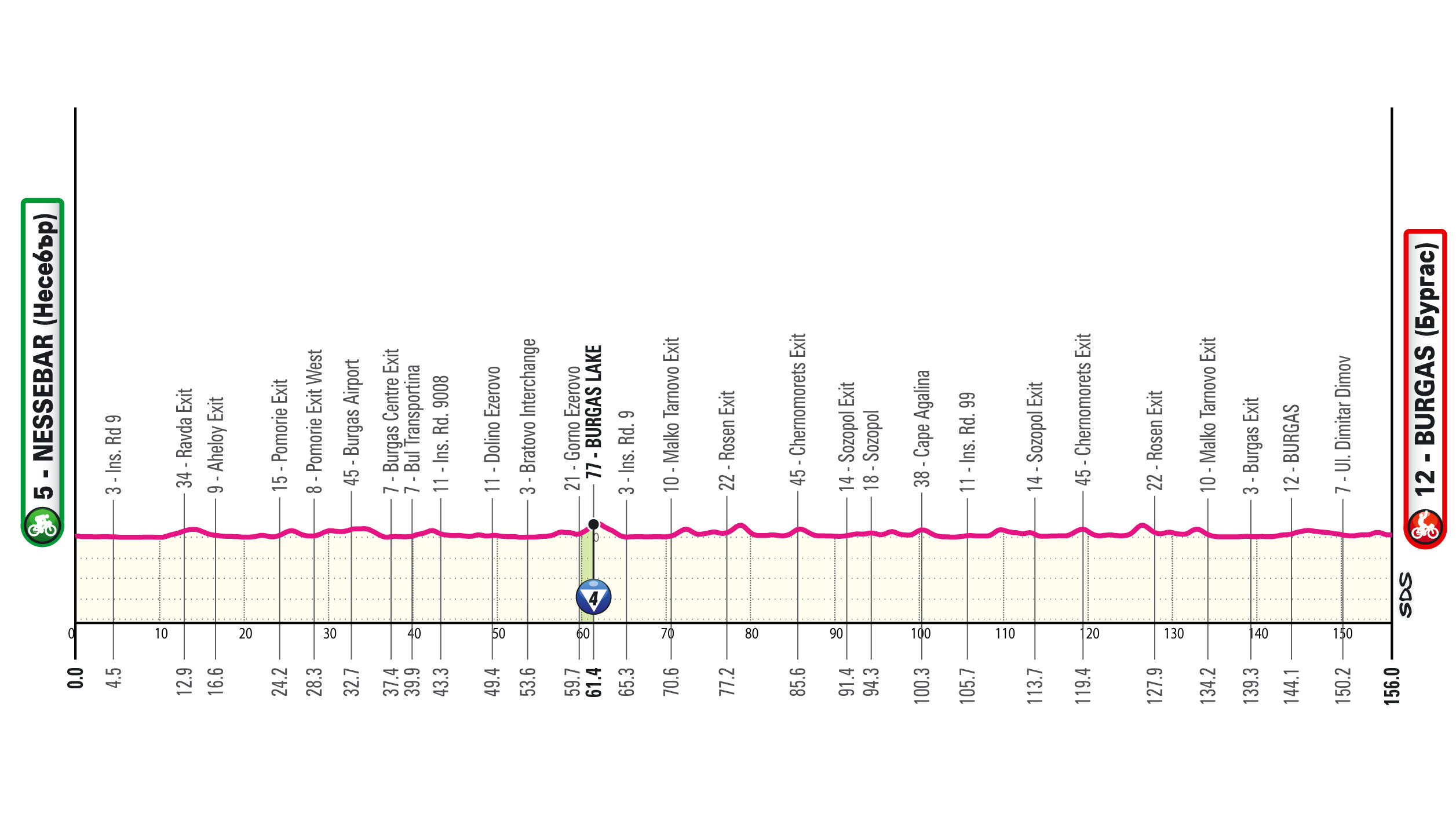

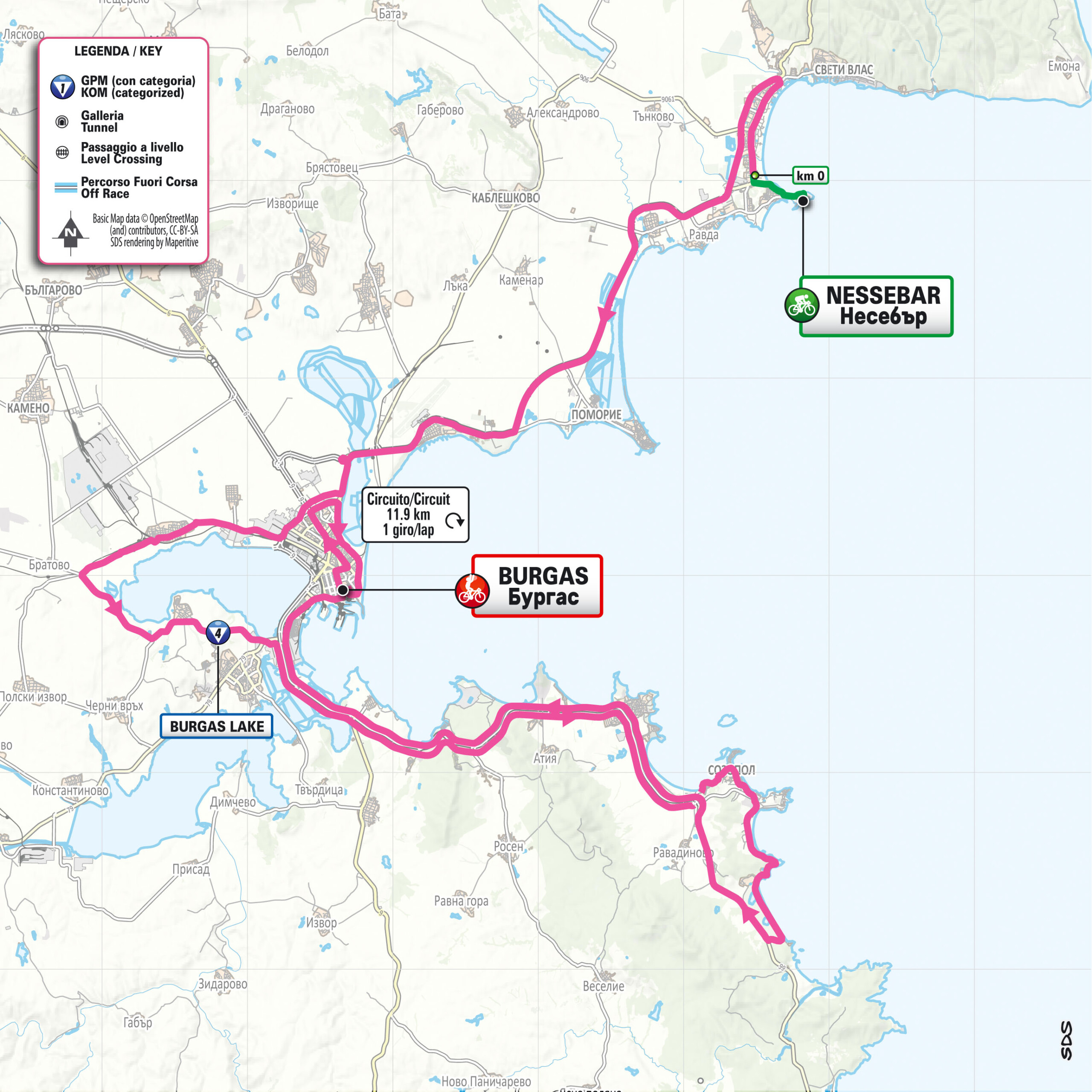

Stage 1 runs along the Black Sea coast from Nessebar to Burgas. “The first Maglia Rosa will be awarded here,” said Vegni.

Stage 2, from Burgas to Veliko Tarnovo, covers 220 km and features a final climb of 3.5 km at 7.5%, promising early drama. Stage 3 finishes in Sofia, starting from Plovdiv, favoring the sprinters.

“I am pleased to be here this evening and honoured to see that Bulgaria will host the Grande Partenza of one of the most important sporting events in the world,” said Prime Minister Rosen Zhelyazkov. “The Giro d’Italia is not just a race, but a global symbol of tradition and sport, combining athletic competition with culture. Hosting it in our country confirms Bulgaria’s growing role in international sport. It is a unique opportunity to showcase our history, traditions and our value as a host nation, ready to provide everything needed for a memorable Grande Partenza.”

First Week: Italy Awaits

After the first rest day on 11 May, the race returns to Italy. Sprinters will find opportunities, though mountain stages will intervene. The peloton ascends the Blockhaus via the feared Roccamorice side, marking the first summit finish in Italy.

“The first summit finish will be on the Blockhaus after a long stage, and it will already be very demanding. You won’t be able to hide,” said Vincenzo Nibali. “In general, the finishes are very challenging, with short and explosive stages also in the second week. The Aosta stage, with almost 4,000 metres of elevation gain, will be crucial and you will need a strong team for support. The final week represents the heart of the Giro d’Italia. The Dolomites can really make the difference.”

The week closes with the “Muri” stage to Fermo and the Apennine summit finish at Corno alle Scale, returning 22 years after Gilberto Simoni’s victory in 2004.

Second Week: Tuscan Time Trial and Alpine Assault

Racing resumes after the second rest day on 18 May with the 40.2 km individual time trial from Viareggio to Massa, the Tappa Bartali. “It’s an edition entirely in Tuscany,” Vegni noted.

Three more stages follow, blending demanding finales and sprinter-friendly finishes. The weekend leads the peloton to the Aosta Valley for a punishing 133 km stage to Pila, featuring over 4,400 m of elevation gain. Milan hosts a sprint finish on Sunday, celebrating its 90th stage finish in Giro history.

Simon Yates reflected on the route: “The emotions I felt at the end of this Giro were incredible and I really hope to experience them again. In 2018 I had a great race, but also a painful ending with the crisis in the final stage. In the years after, I came back hoping to get my revenge, but it never really worked out. Still, in the back of my mind, I always wanted to try again. This year, I finally managed to do it. When I saw the Colle delle Finestre on the route, my first reaction was: ‘Oh, not again.’ But I was able to fight back and come up with something special. The route of the upcoming edition is very demanding. Blockhaus is a very tough climb, I rode it in 2022, and it can really change the race. The Aosta stage will probably be the key one: it’s extremely hard, but it suits my characteristics quite well.”

Third Week: Dolomites, Switzerland, and the Final Showdown

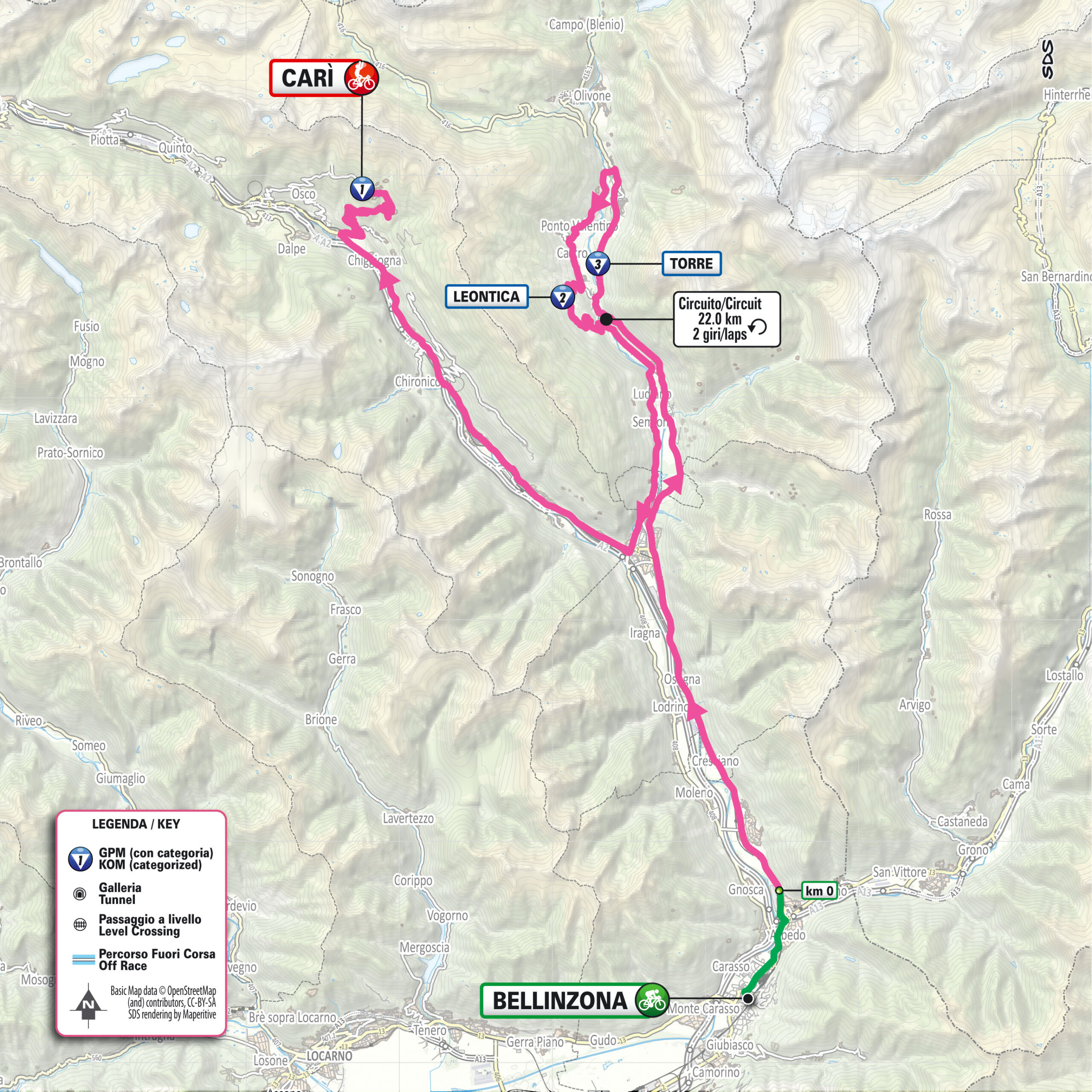

The final week begins with a short but intense stage entirely in Switzerland, from Bellinzona to Carì.

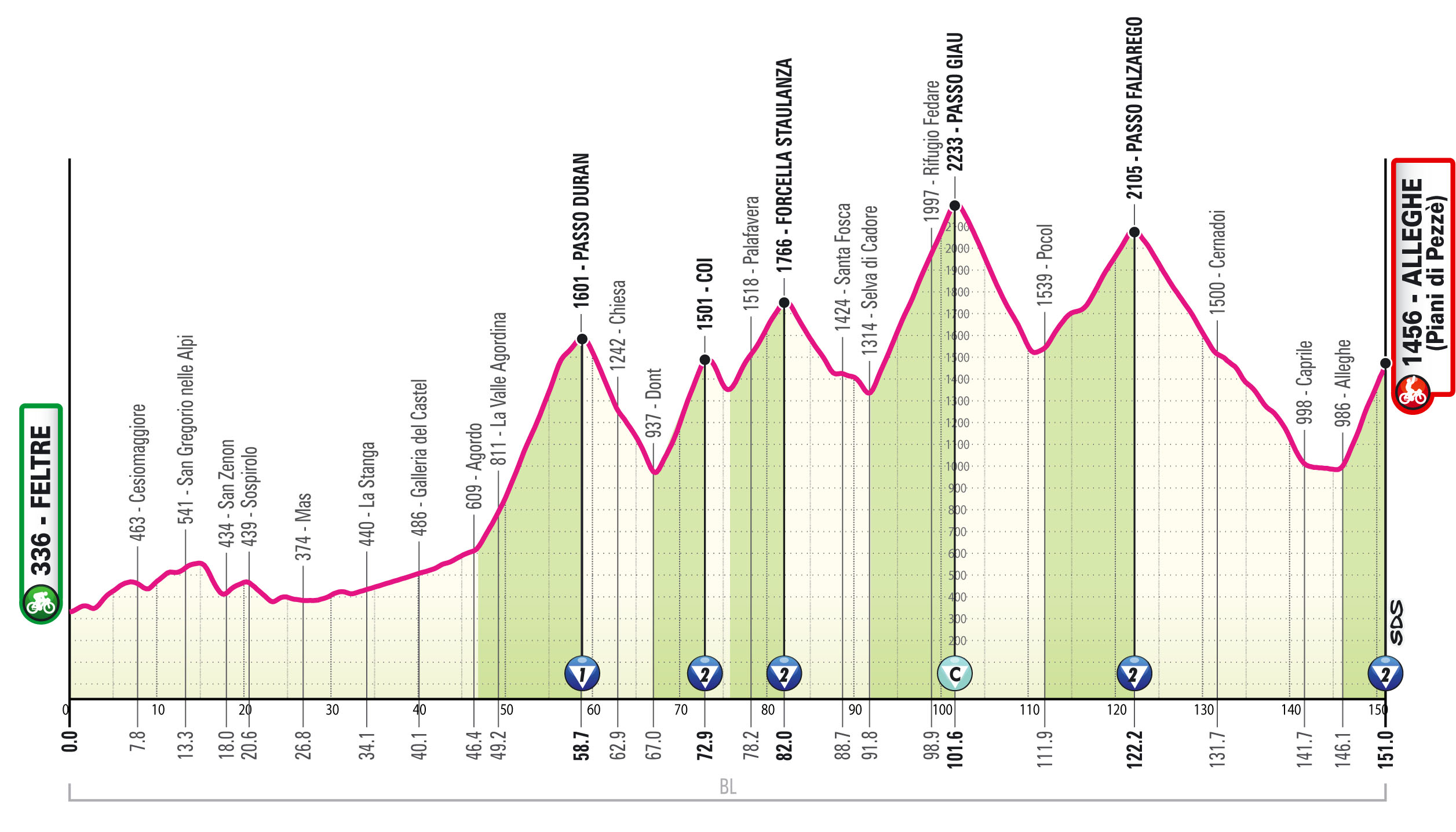

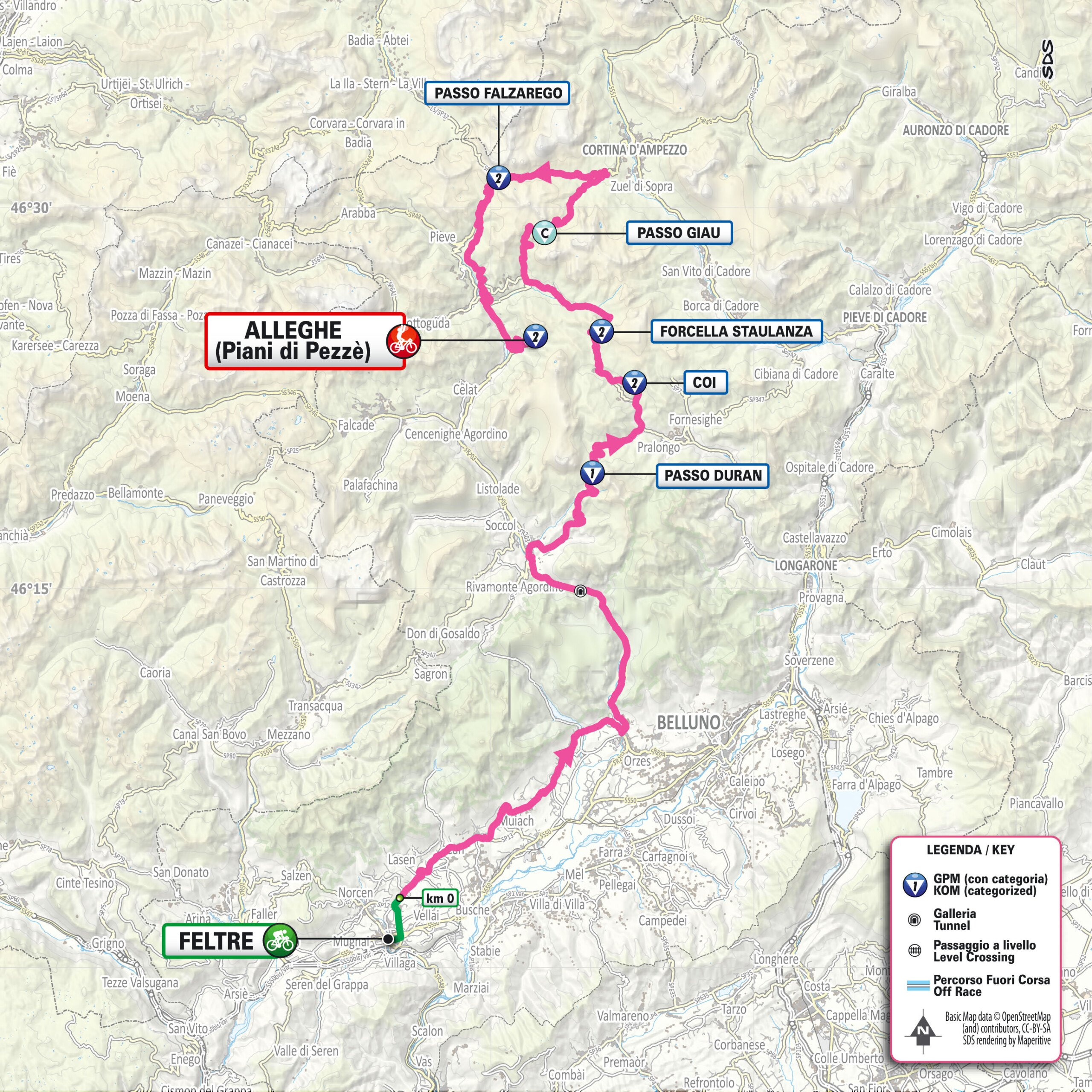

Two mixed stages set the stage for the final battles. The Dolomite queen stage stretches from Feltre to Piani di Pezzè, revisiting a route made famous by Marco Pantani in 1992. Riders will climb the Duran, Staulanza (with the Coi variant), Giau (this year’s Cima Coppi at 2,233 metres), and Falzarego passes.

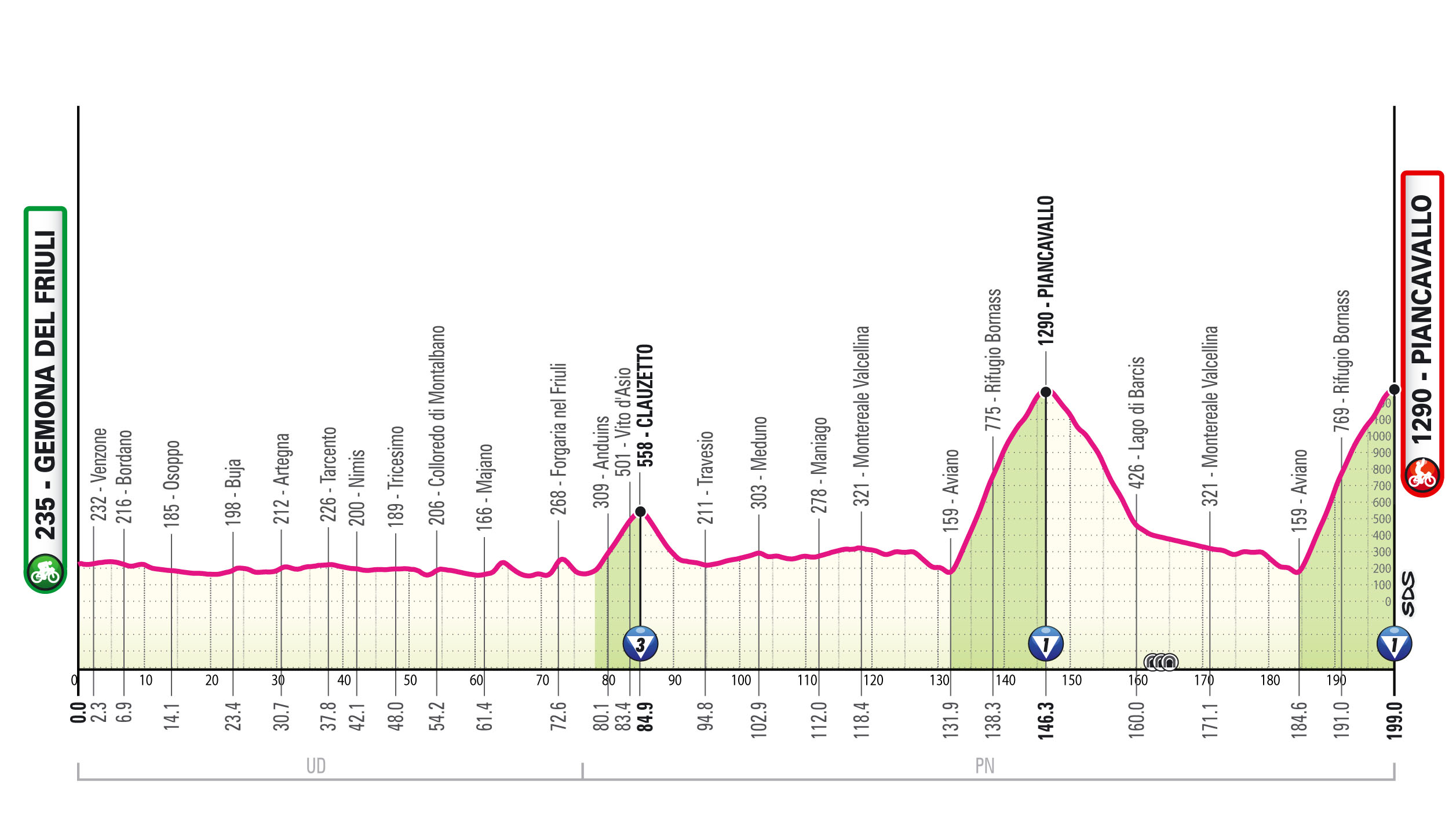

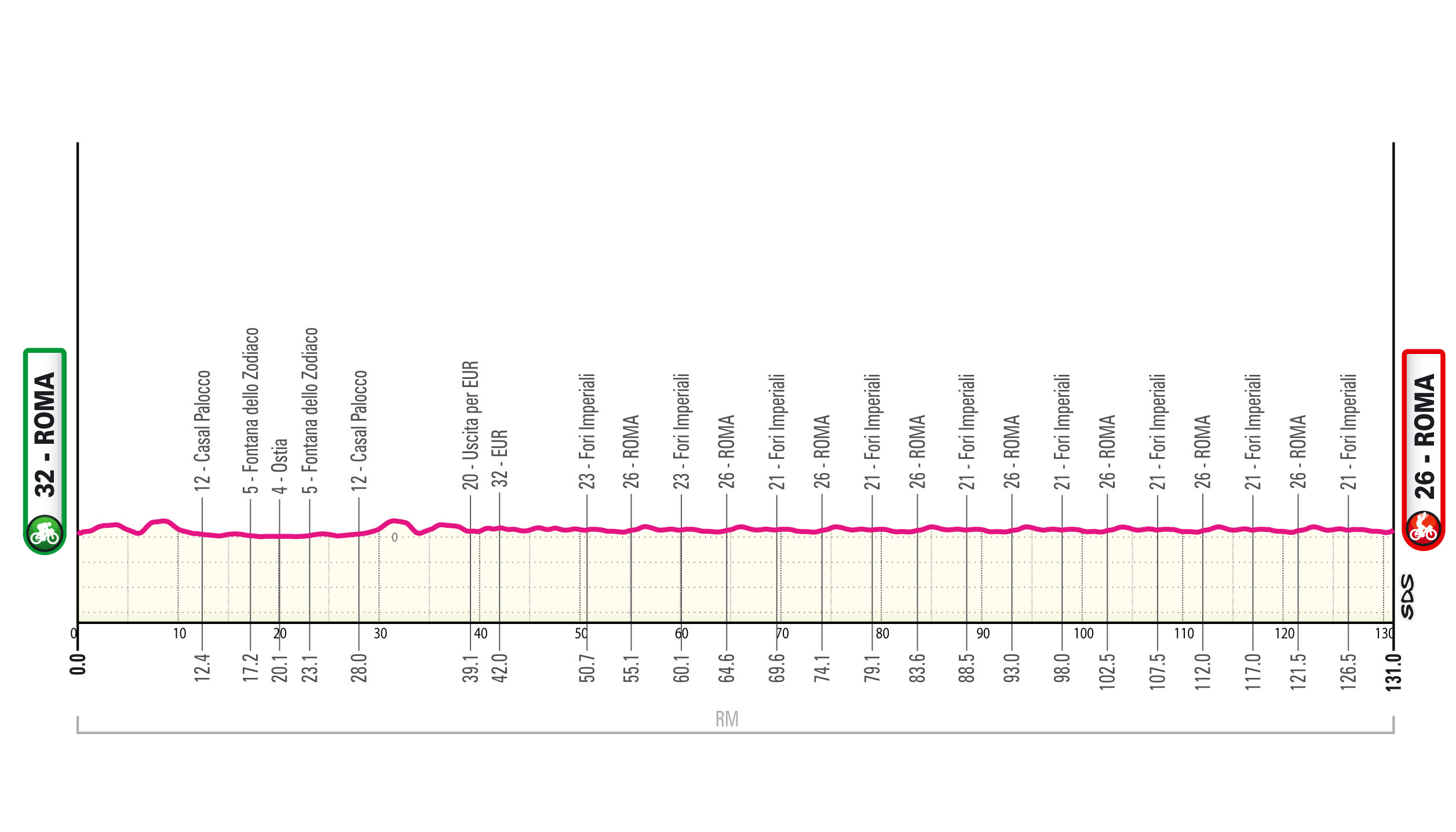

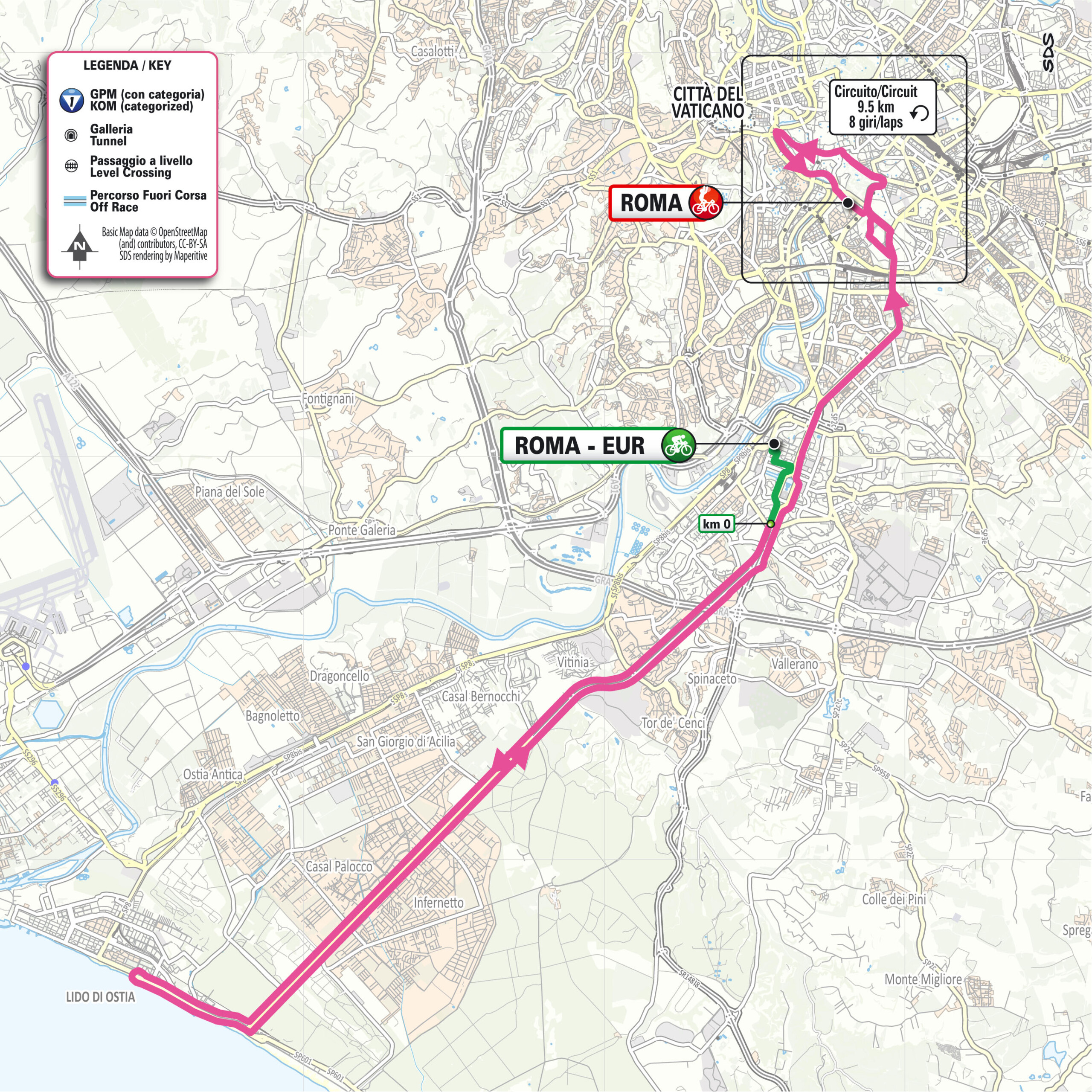

The following day commemorates the Friuli earthquake of 6 May 1976, passing through Gemona del Friuli before climbing Piancavallo twice to decide the general classification. The Giro concludes with the Grande Arrivo in Rome, featuring the traditional parade circuit through the Eternal City.

Numbers & Facts

- Total distance: 3,459 km

- Total elevation gain: 50,000 m

- Foreign Grande Partenza: 16th in Giro history

- Grande Arrivo in Rome: 8th time

- Individual time trial distance: 40.2 km

- Stage finishes in Milan: 90th

- Cima Coppi: Passo Giau (2,233 m) for the 4th time (1973, 2011, 2021)

Giro d’Italia 2026 – Stage Guide

Total distance: 3,459 km

Total elevation gain: 50,000 m

Dates: 8–31 May 2026

Stage 1 – Friday 8 May: Nessebar → Burgas (Bulgaria)

- Distance: 156 km

- Black Sea coast route

- Sprinter-friendly finish

- First Maglia Rosa awarded

Stage 2 – Saturday 9 May: Burgas → Veliko Tarnovo (Bulgaria)

- Distance: 220 km

- Final climb: 3.5 km at 7.5%

- Early test for GC contenders

Stage 3 – Sunday 10 May: Plovdiv → Sofia (Bulgaria)

- Distance: 174 km

- Sprint-favouring finish

Rest Day – Monday 11 May

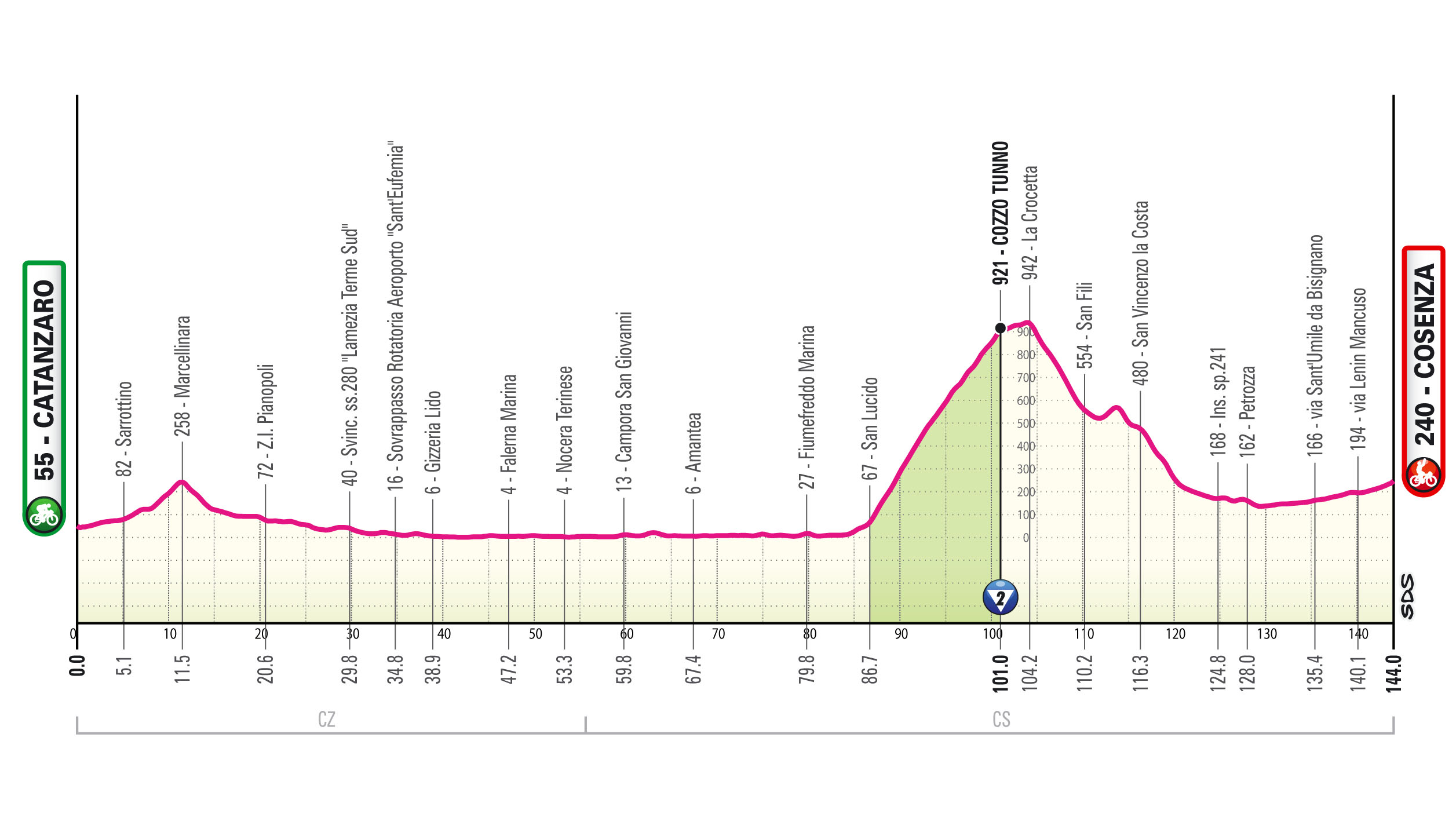

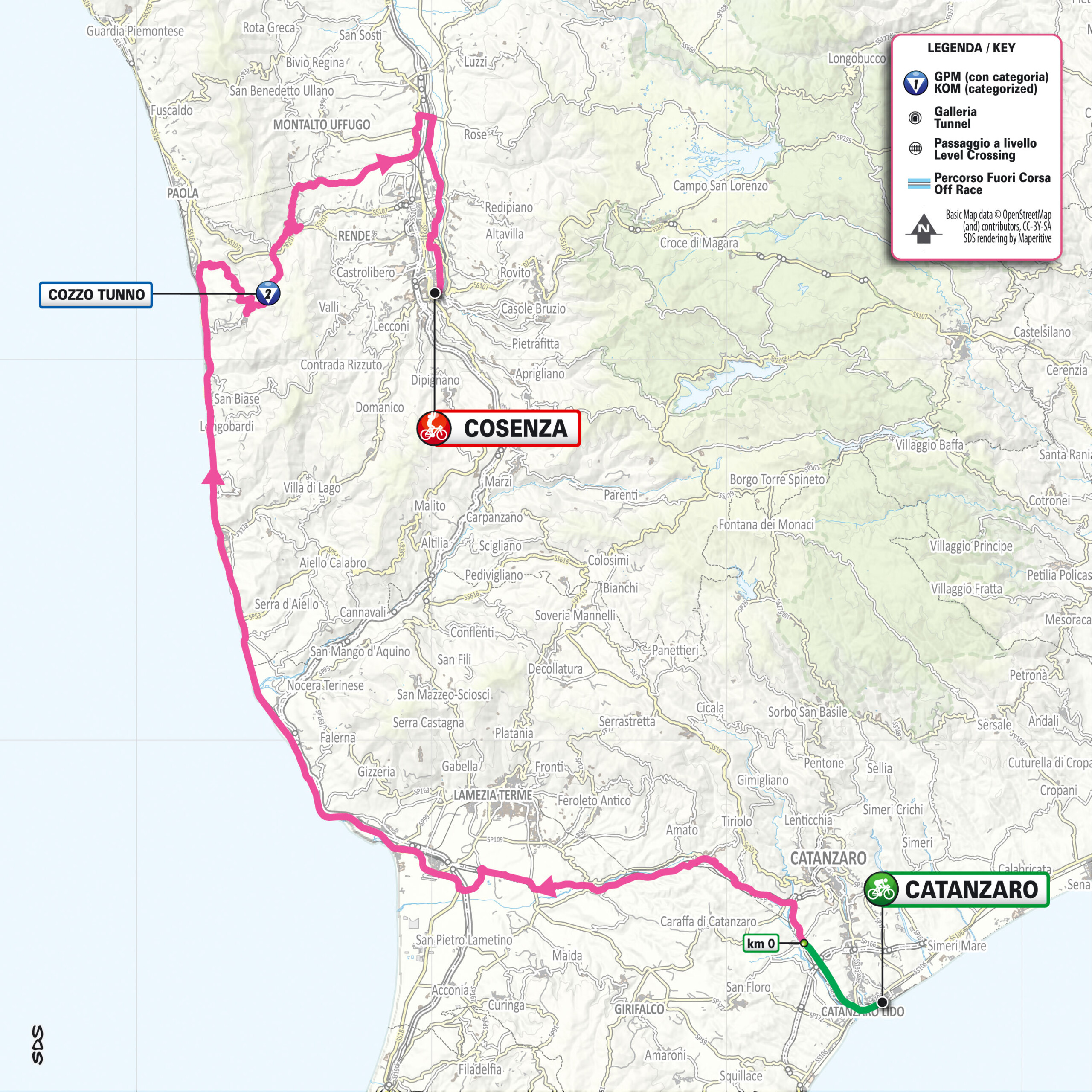

Stage 4 – Tuesday 12 May: Catanzaro → Cosenza

- Distance: 144 km

- Medium-mountain stage

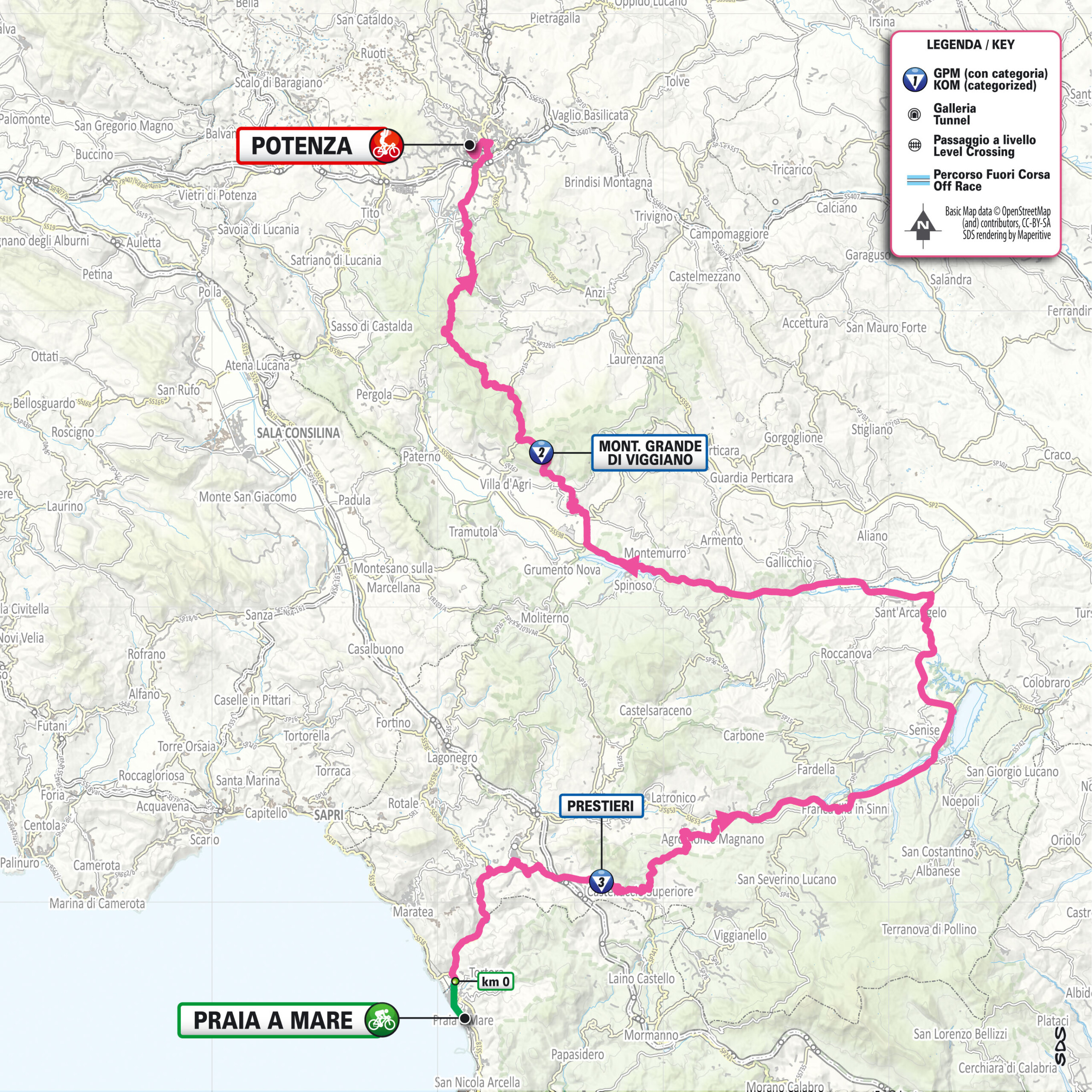

Stage 5 – Wednesday 13 May: Praia a Mare → Potenza

- Distance: 204 km

- Medium-mountain stage

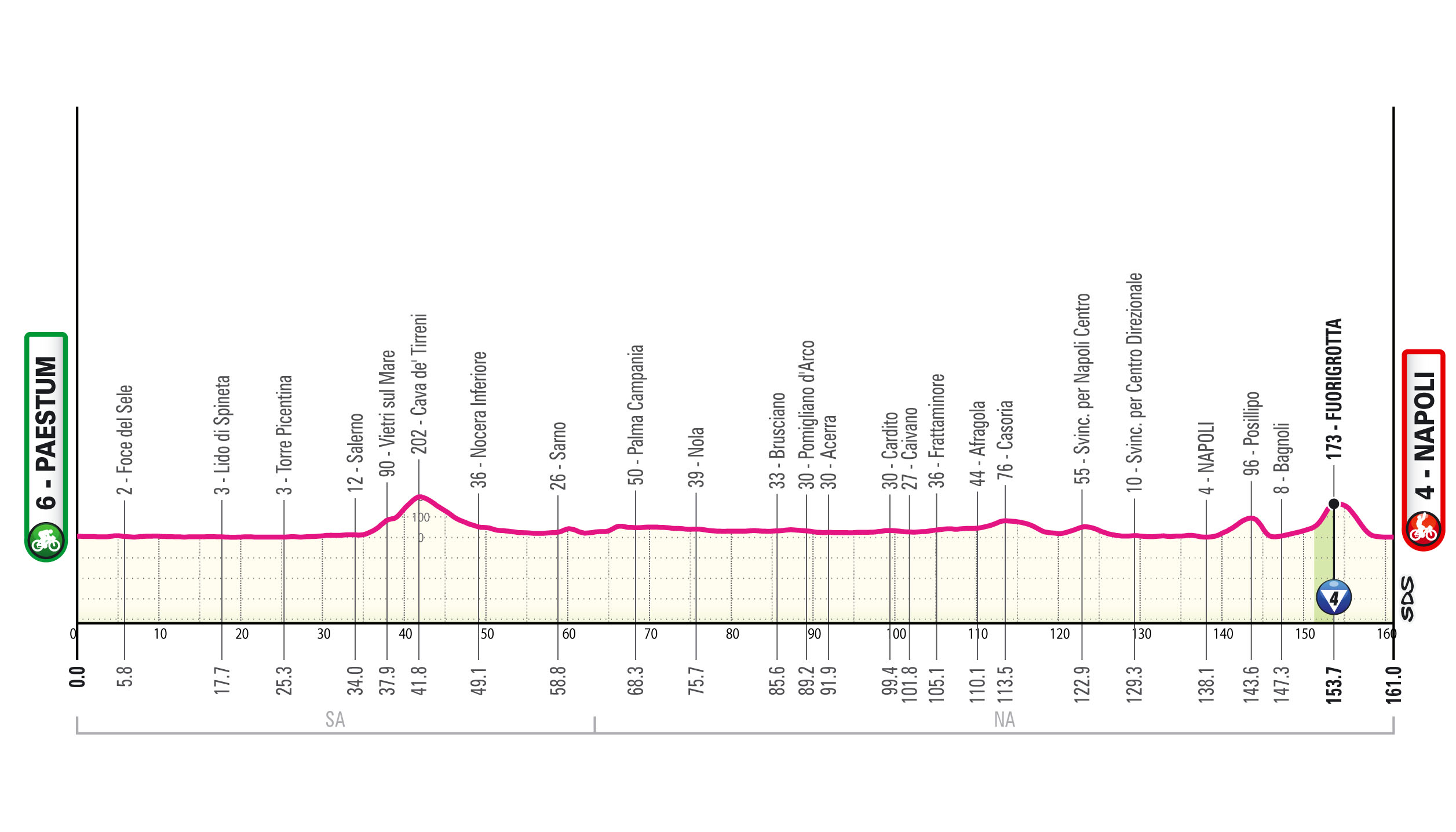

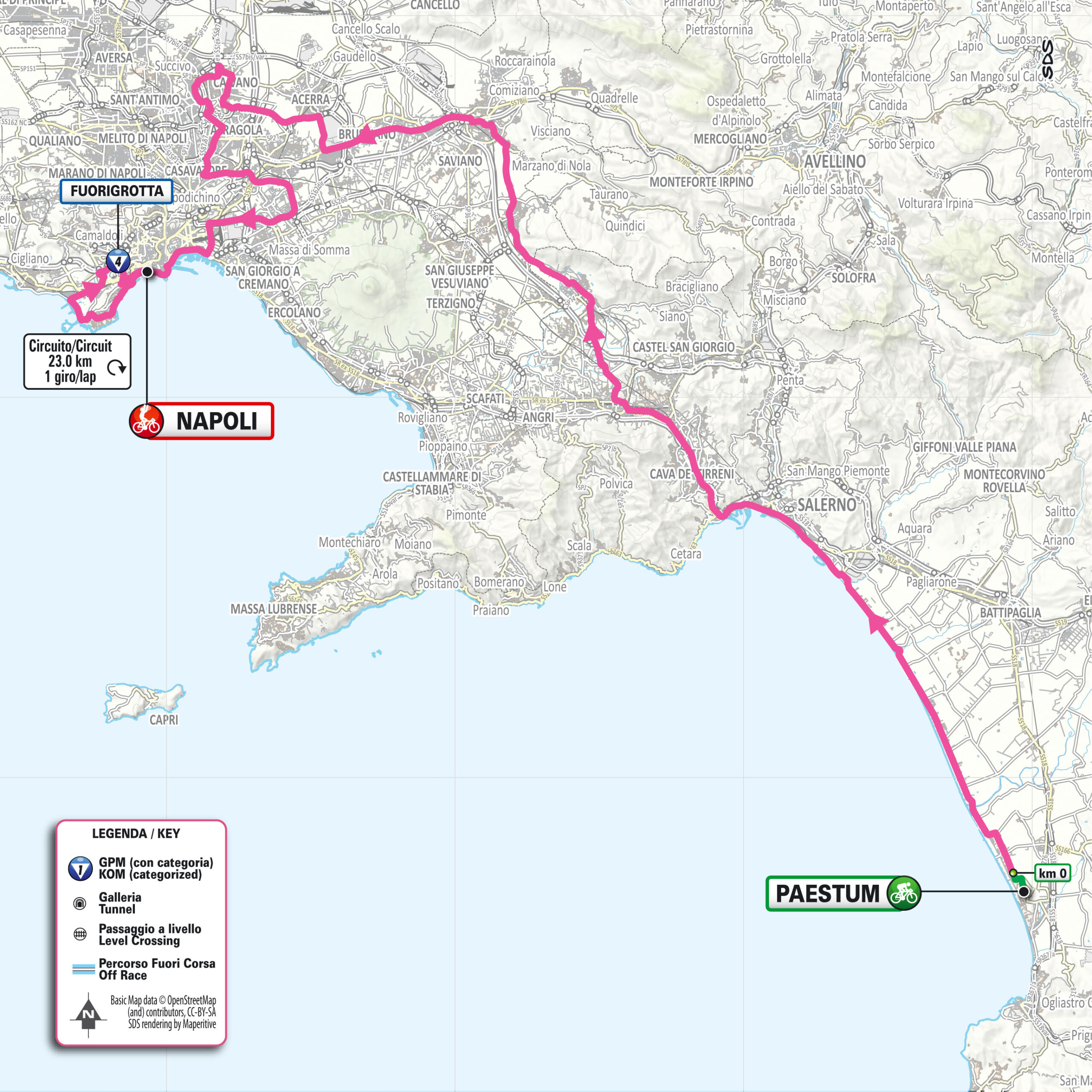

Stage 6 – Thursday 14 May: Paestum → Napoli

- Distance: 161 km

- Sprinter-friendly

Stage 7 – Friday 15 May: Formia → Blockhaus

- Distance: 246 km

- First major summit finish

- Key GC stage

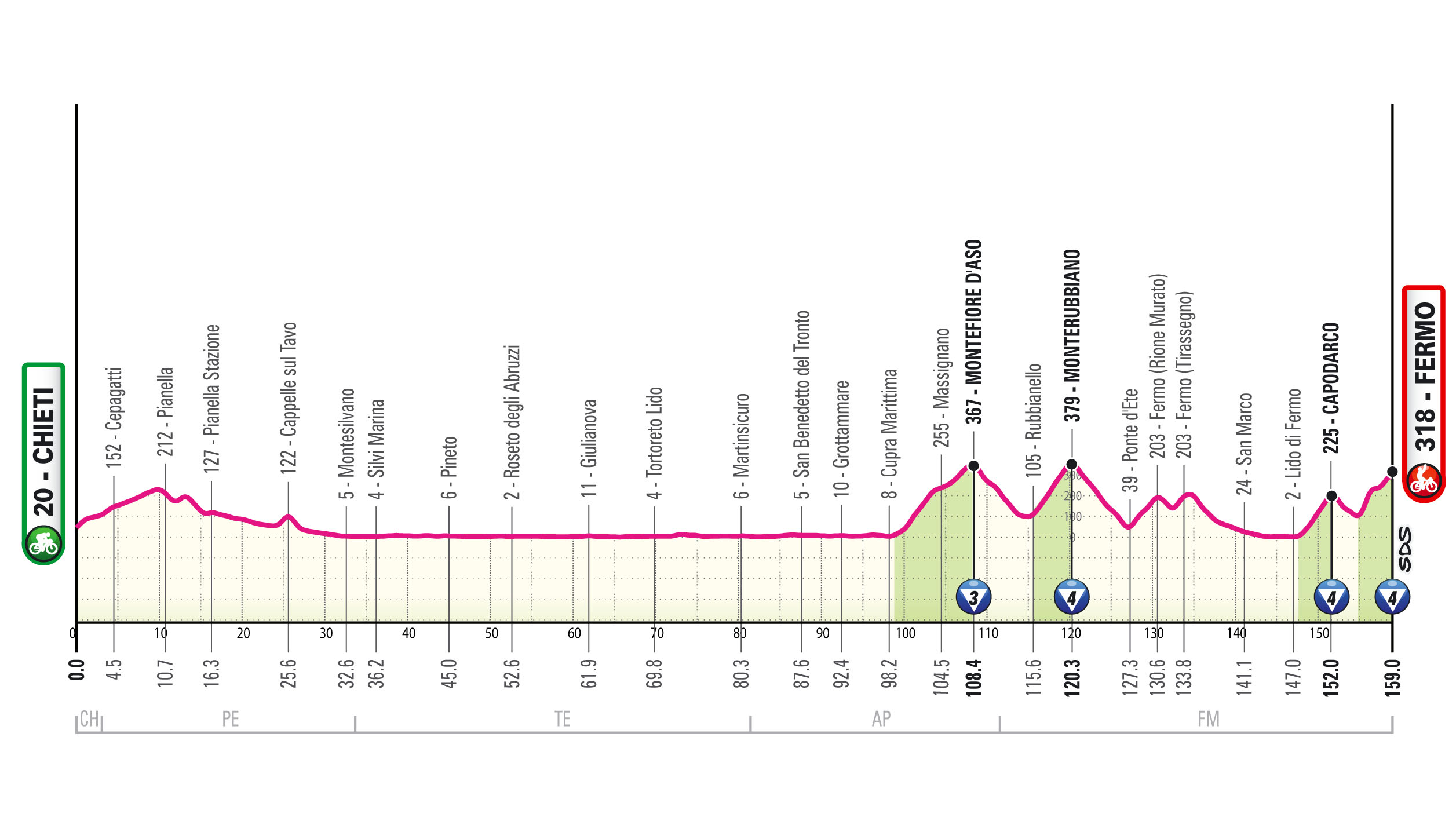

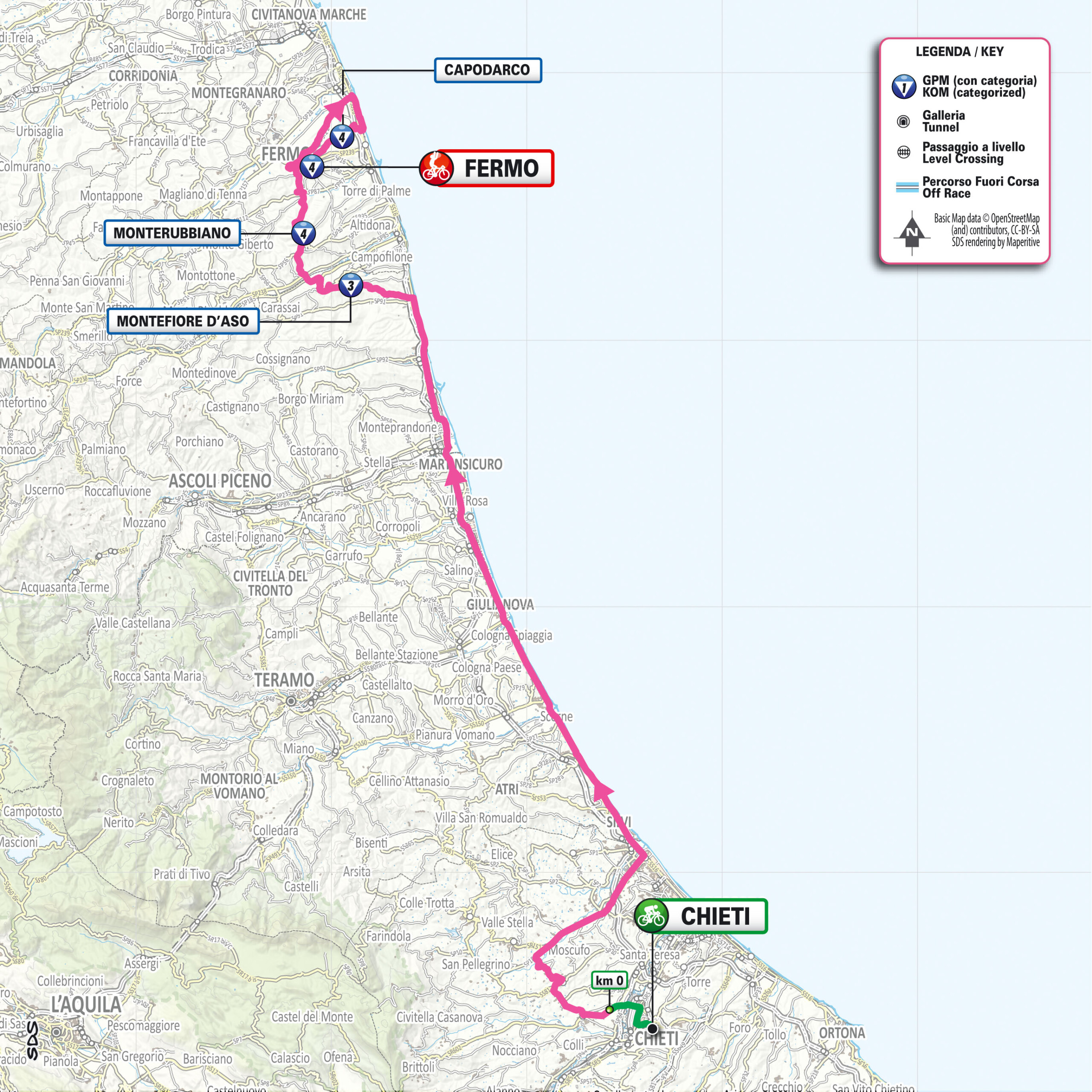

Stage 8 – Saturday 16 May: Chieti → Fermo

- Distance: 159 km

- “Muri” stage, featuring punchy climbs

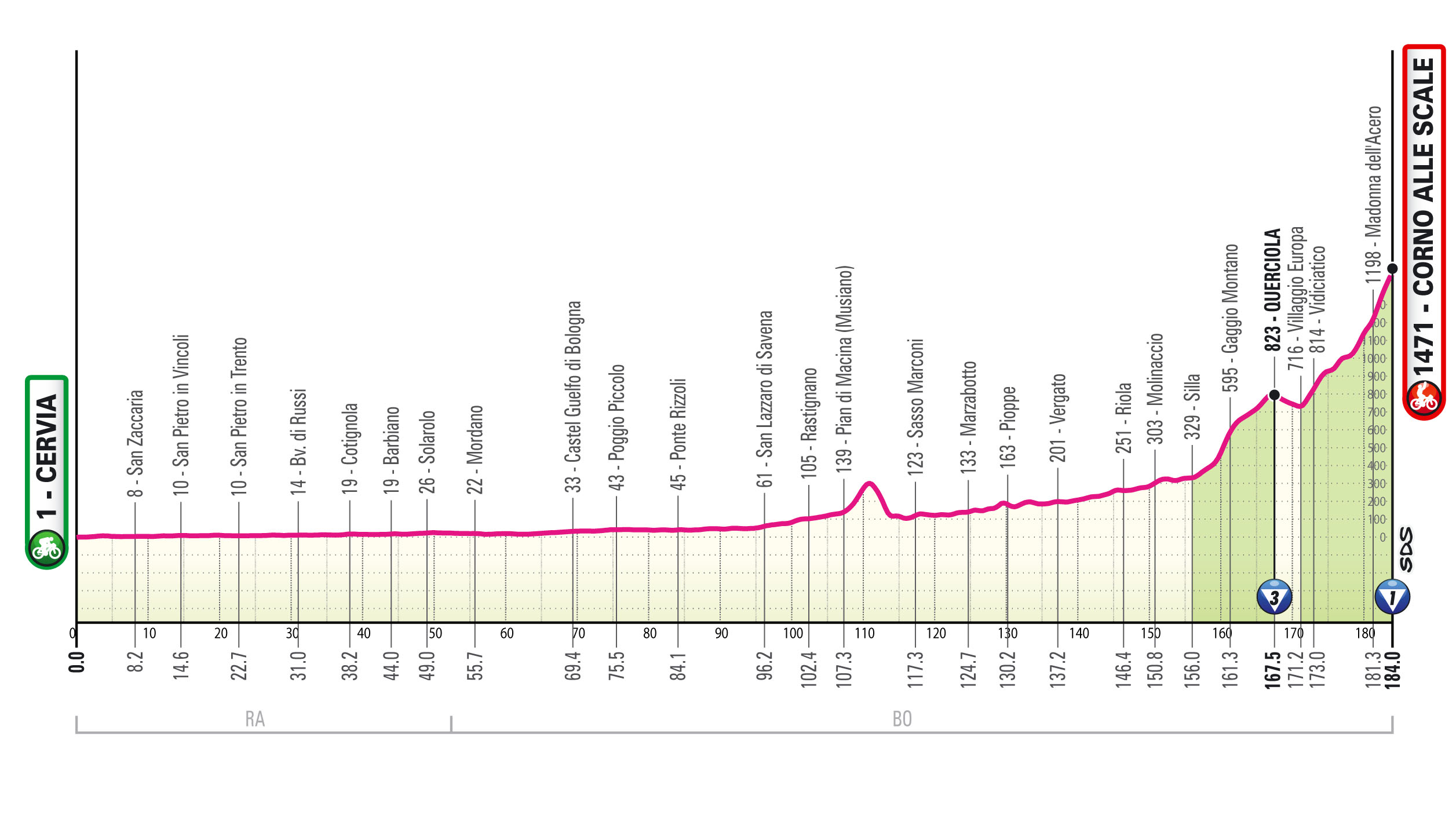

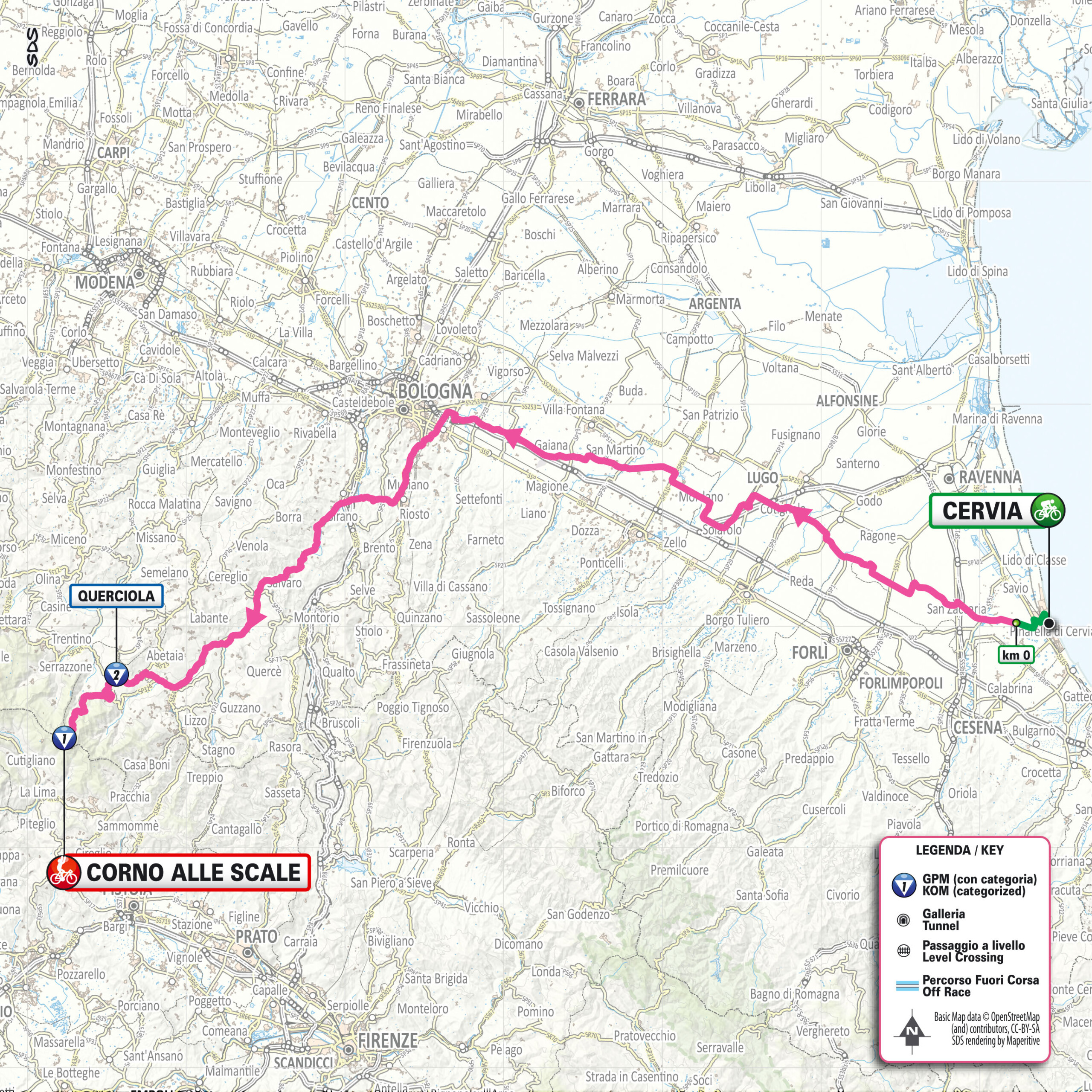

Stage 9 – Sunday 17 May: Cervia → Corno alle Scale

- Distance: 184 km

- Apennine summit finish

- Returns 22 years after Simoni’s 2004 victory

Rest Day – Monday 18 May

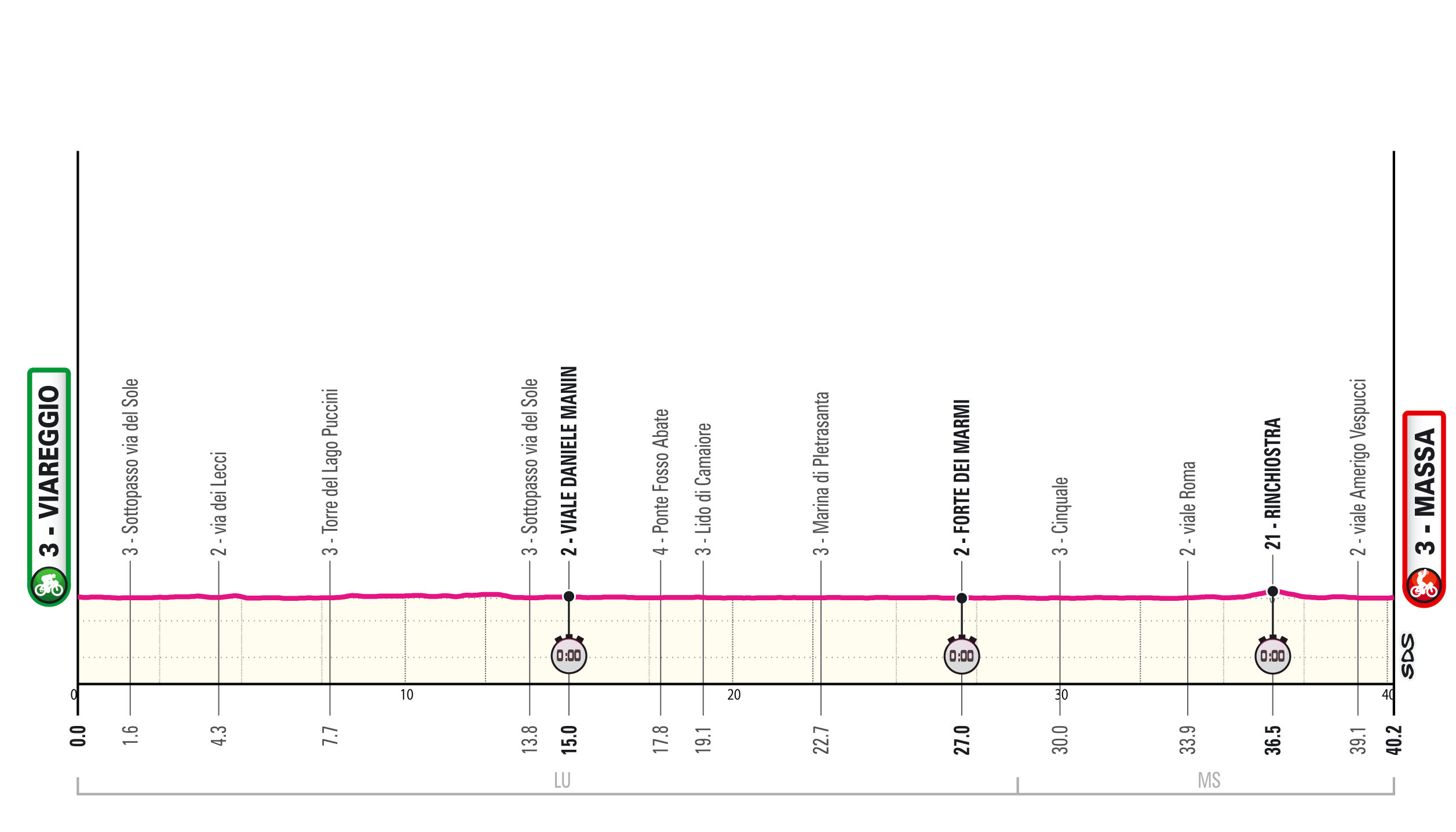

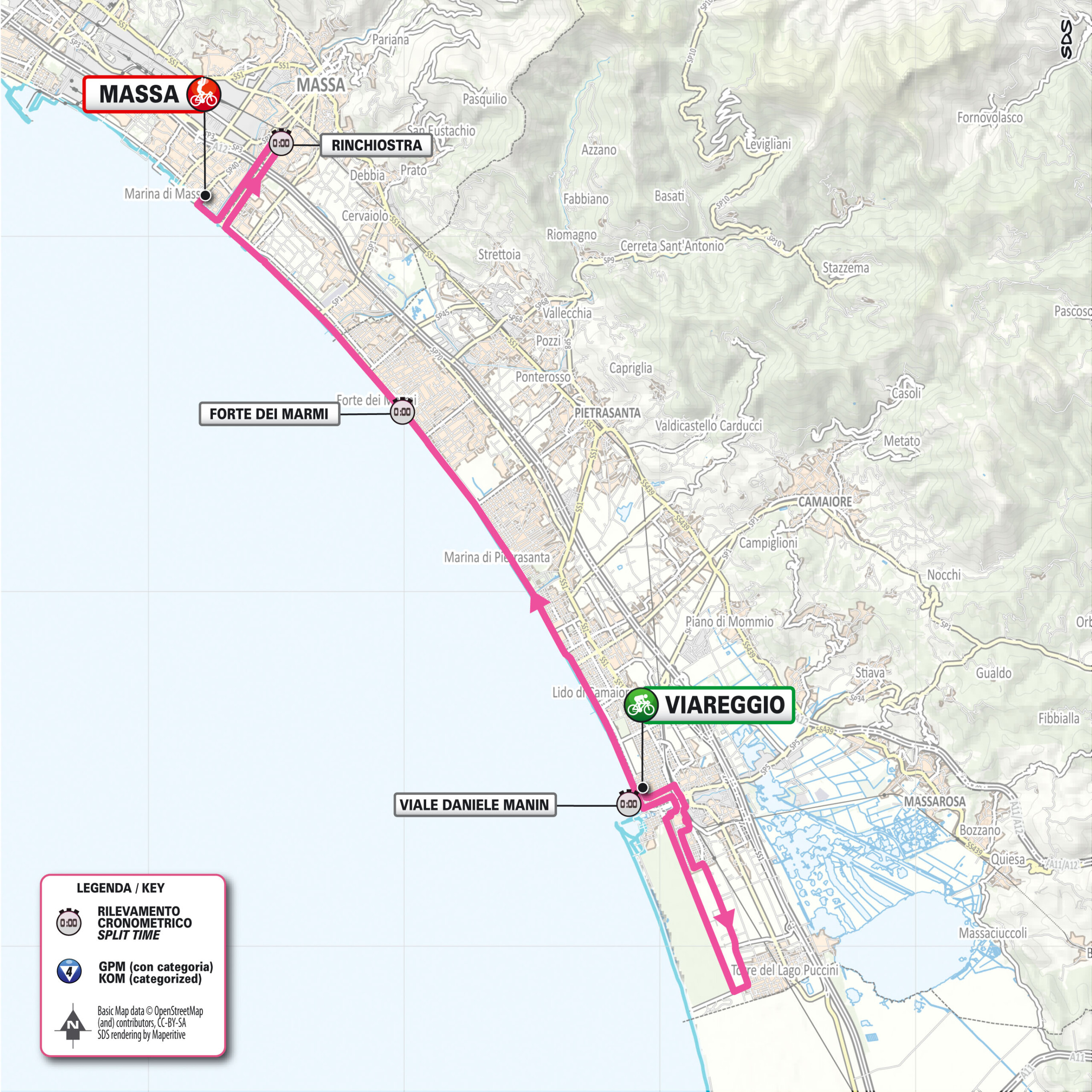

Stage 10 – Tuesday 19 May: Viareggio → Massa (TUDOR ITT)

- Distance: 40.2 km

- Individual time trial (Tappa Bartali)

- Crucial for GC riders

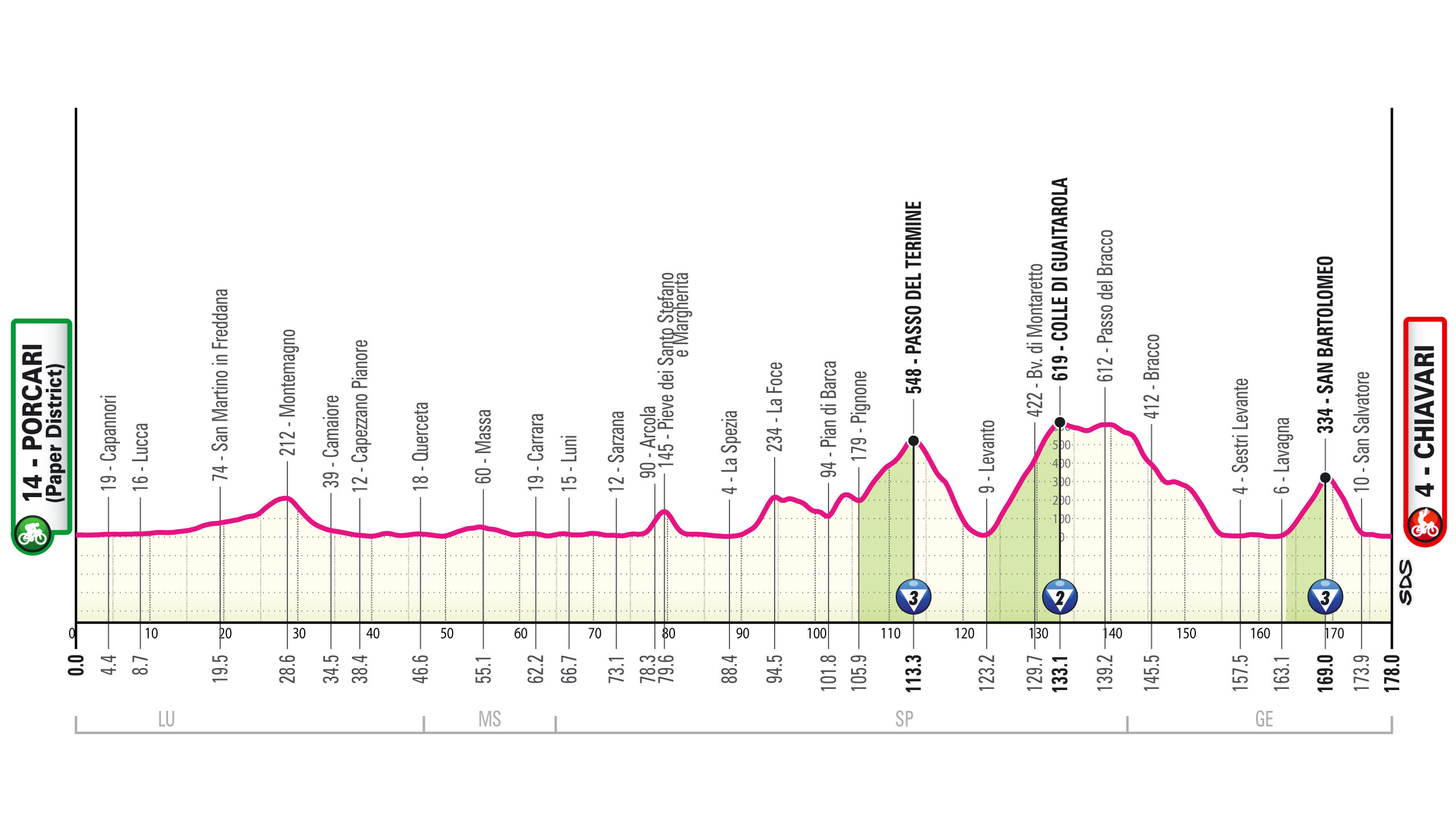

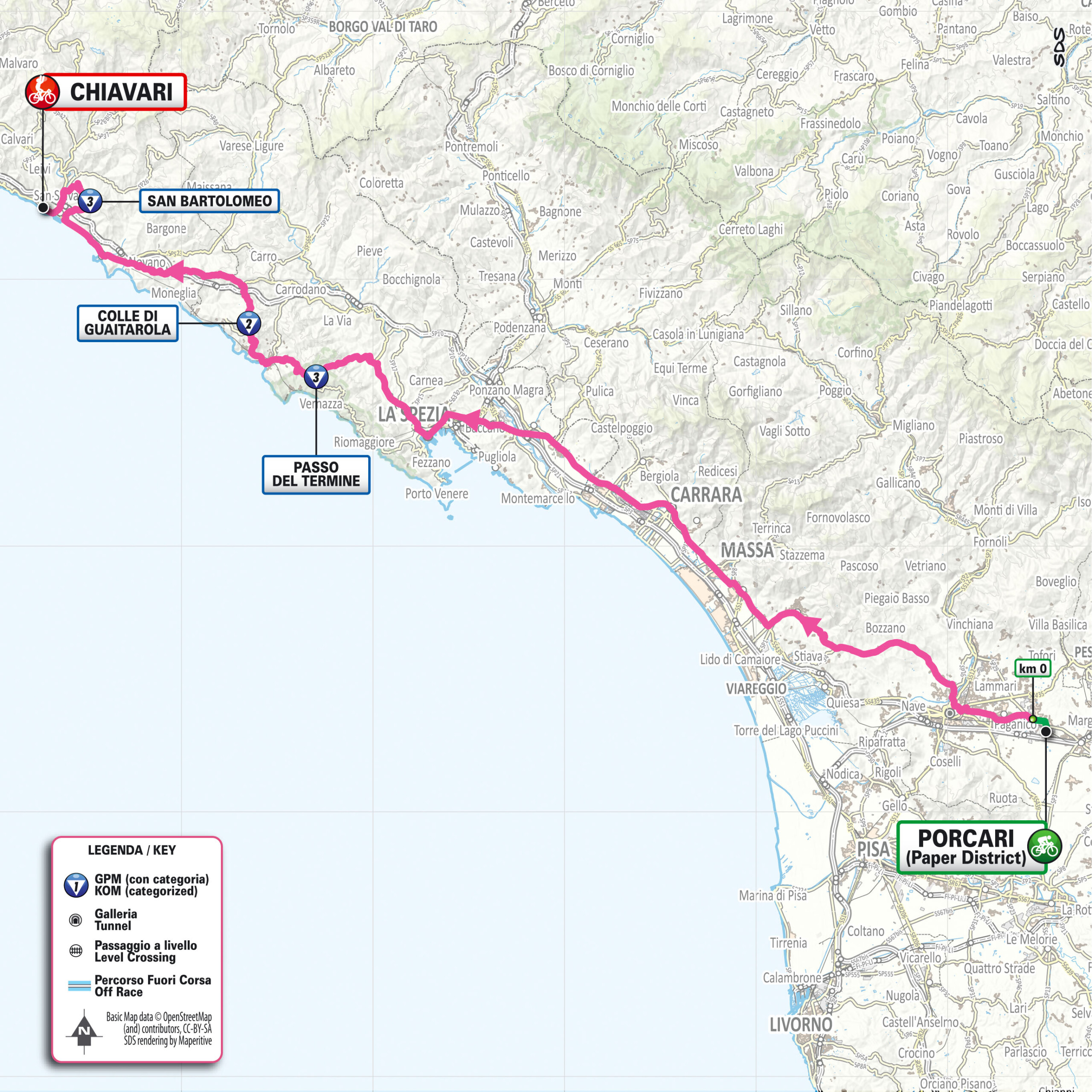

Stage 11 – Wednesday 20 May: Porcari (Paper District) → Chiavari

- Distance: 178 km

- Medium stage

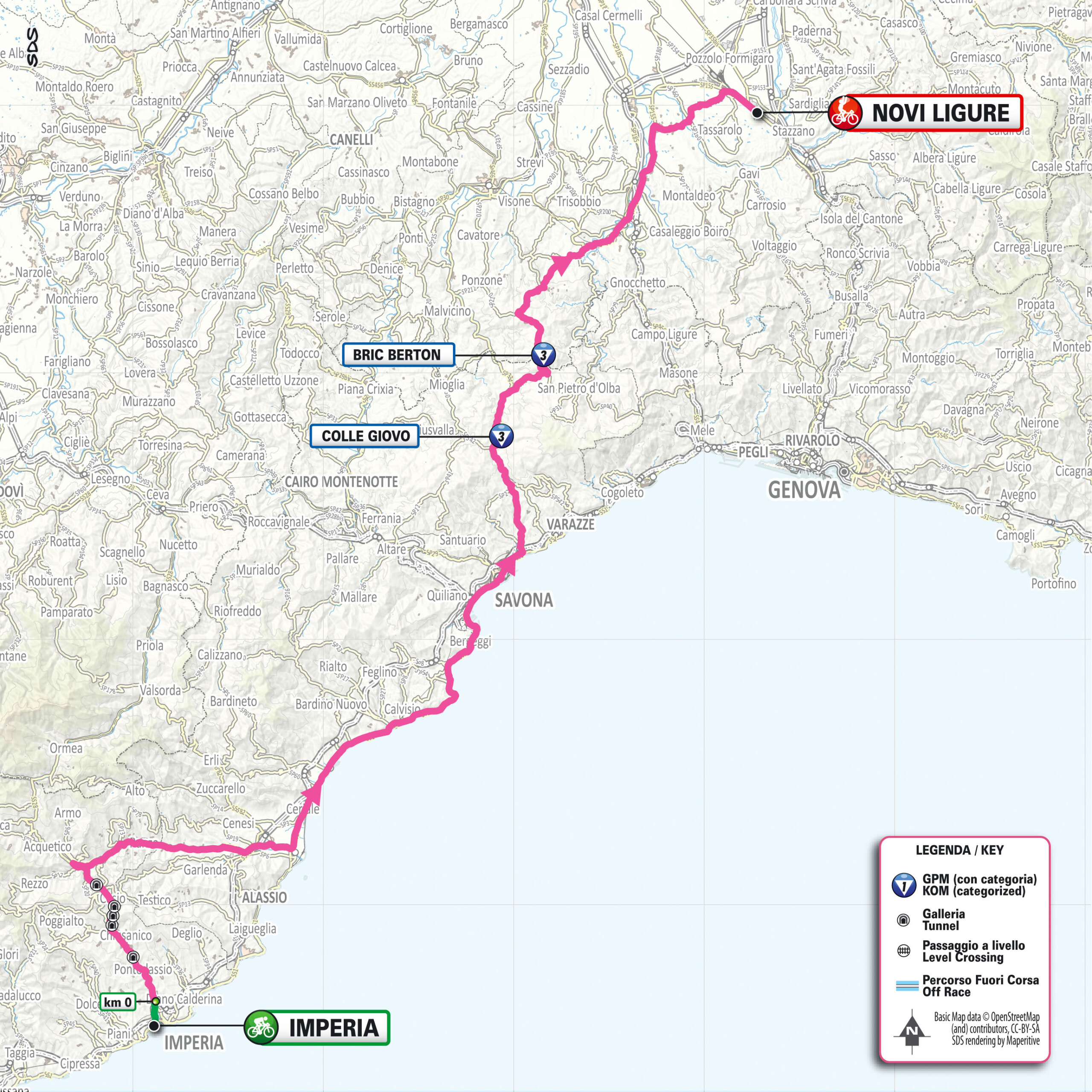

Stage 12 – Thursday 21 May: Imperia → Novi Ligure

- Distance: 177 km

- Likely sprinter-friendly

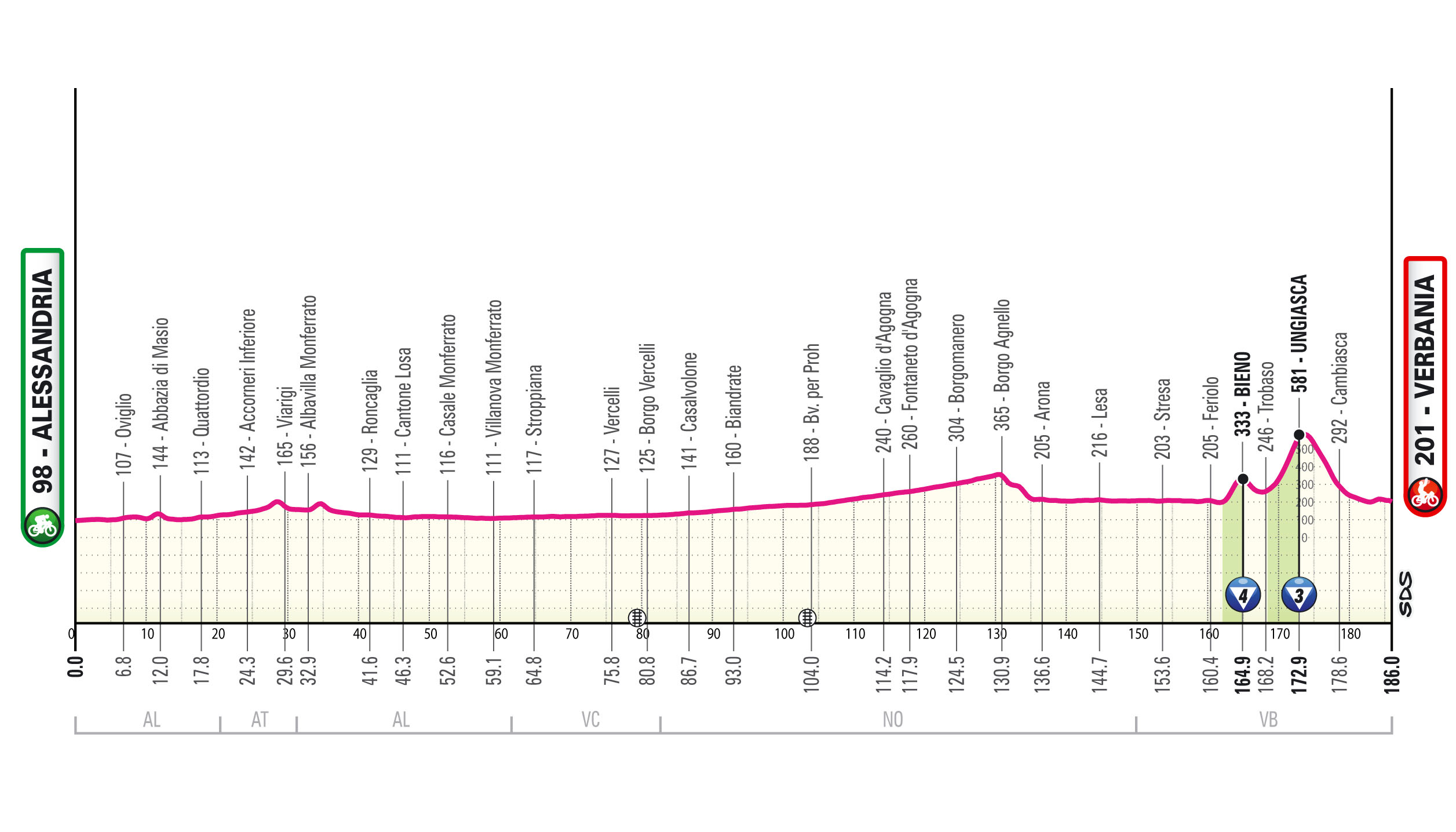

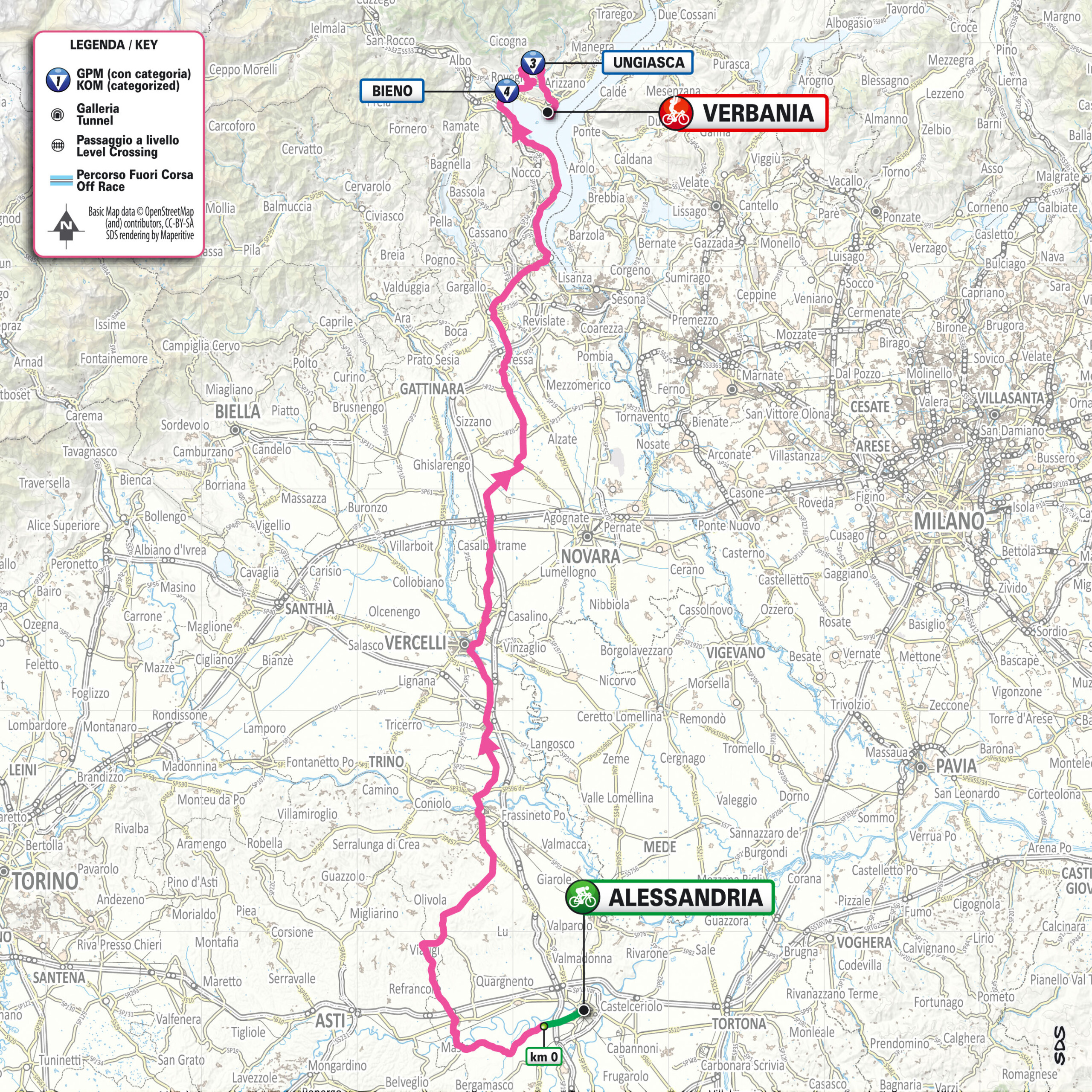

Stage 13 – Friday 22 May: Alessandria → Verbania

- Distance: 186 km

- Mixed stage

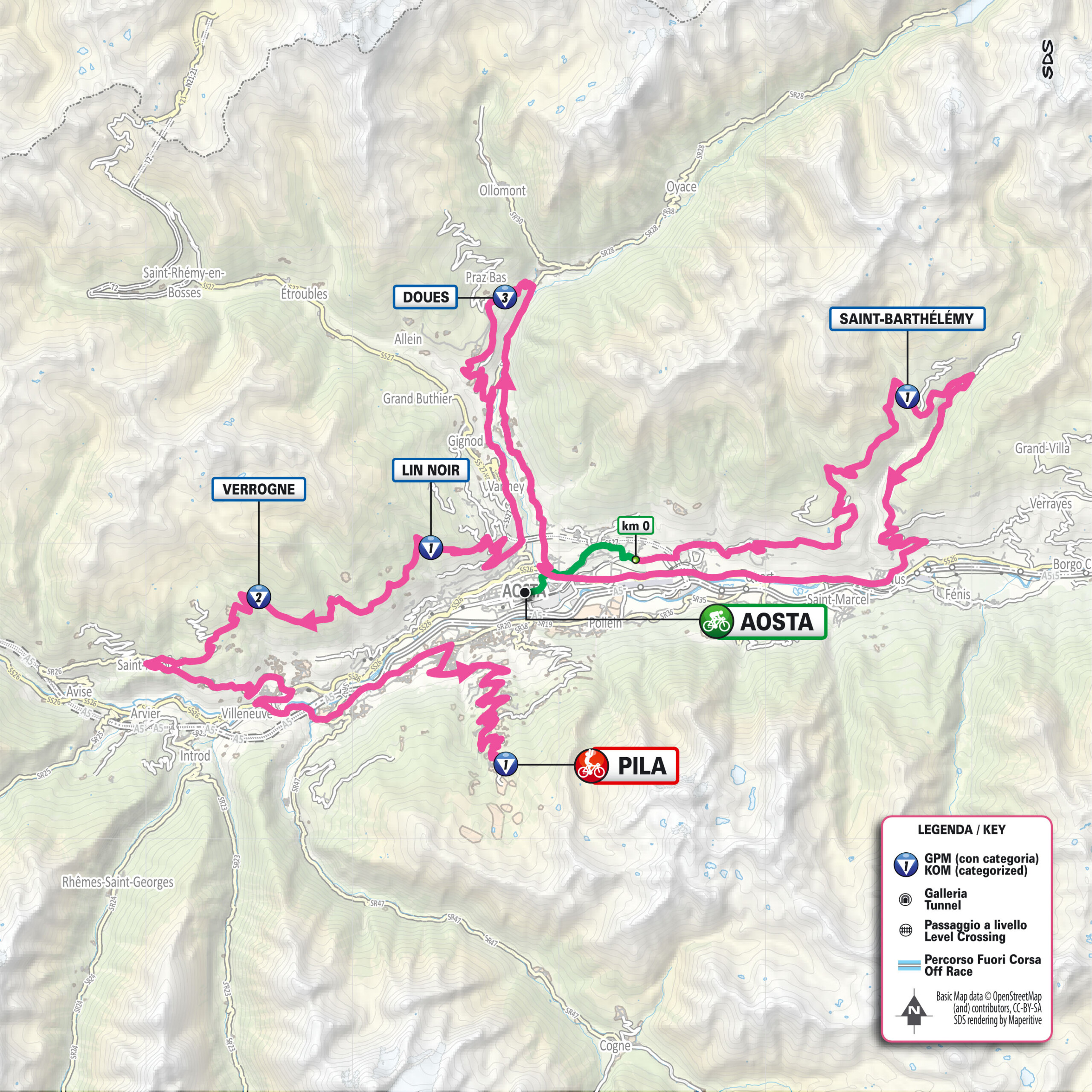

Stage 14 – Saturday 23 May: Aosta → Pila

- Distance: 133 km

- Brutal mountain stage

- 4,400 m elevation gain

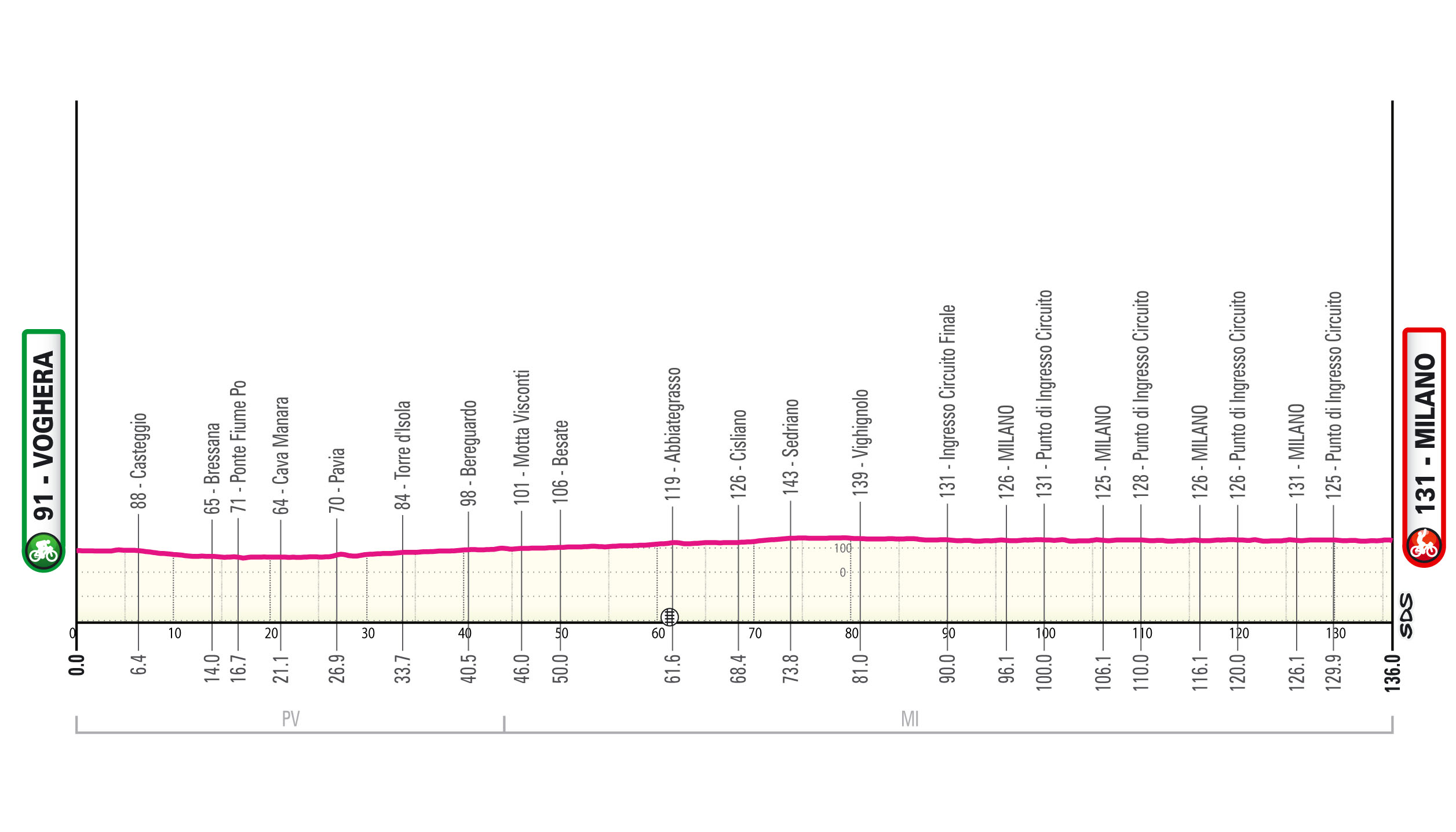

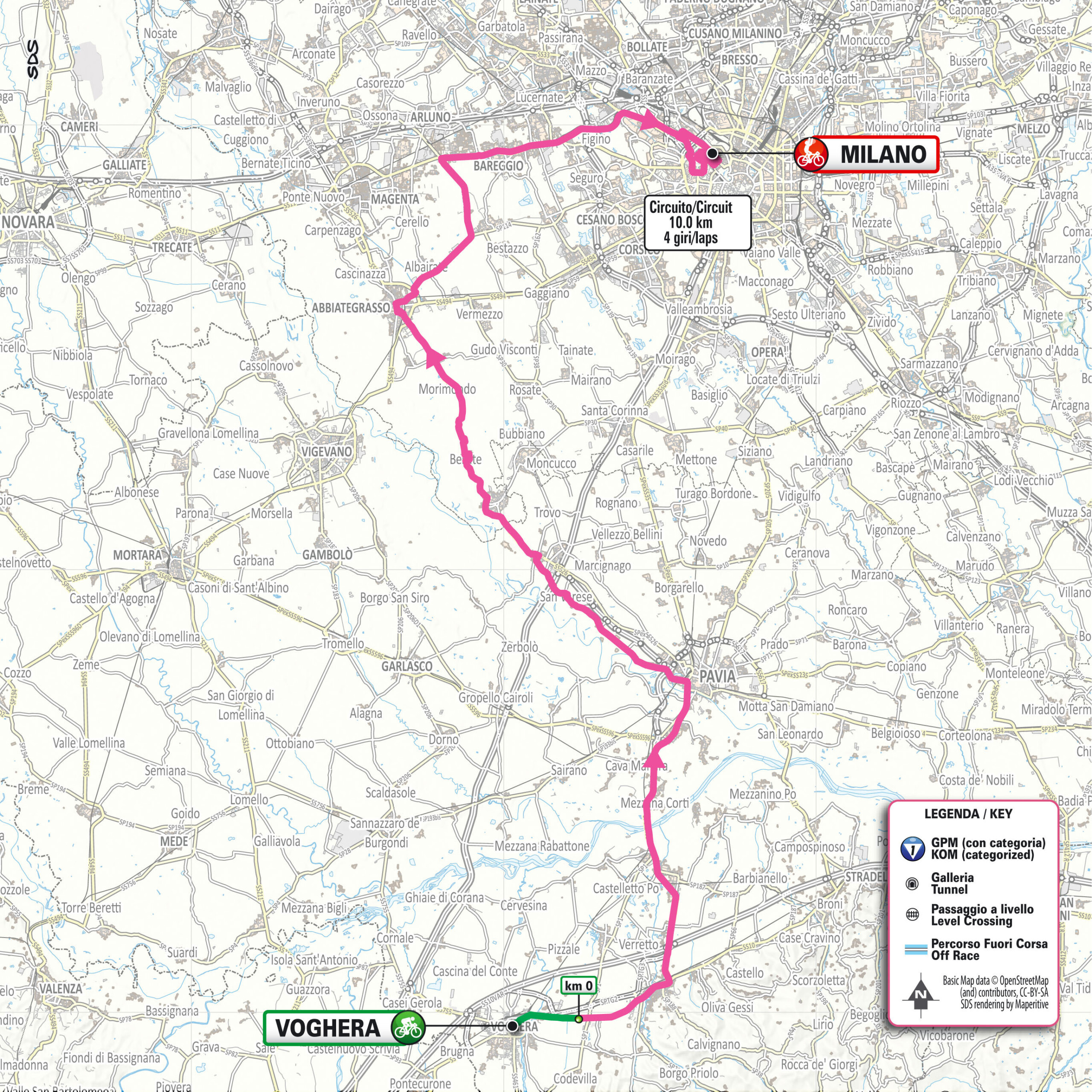

Stage 15 – Sunday 24 May: Voghera → Milano

- Distance: 136 km

- Sprint finish

- Milan hosts its 90th stage finish

Rest Day – Monday 25 May

Stage 16 – Tuesday 26 May: Bellinzona → Carì (Switzerland)

- Distance: 113 km

- Short but intense, mixed terrain

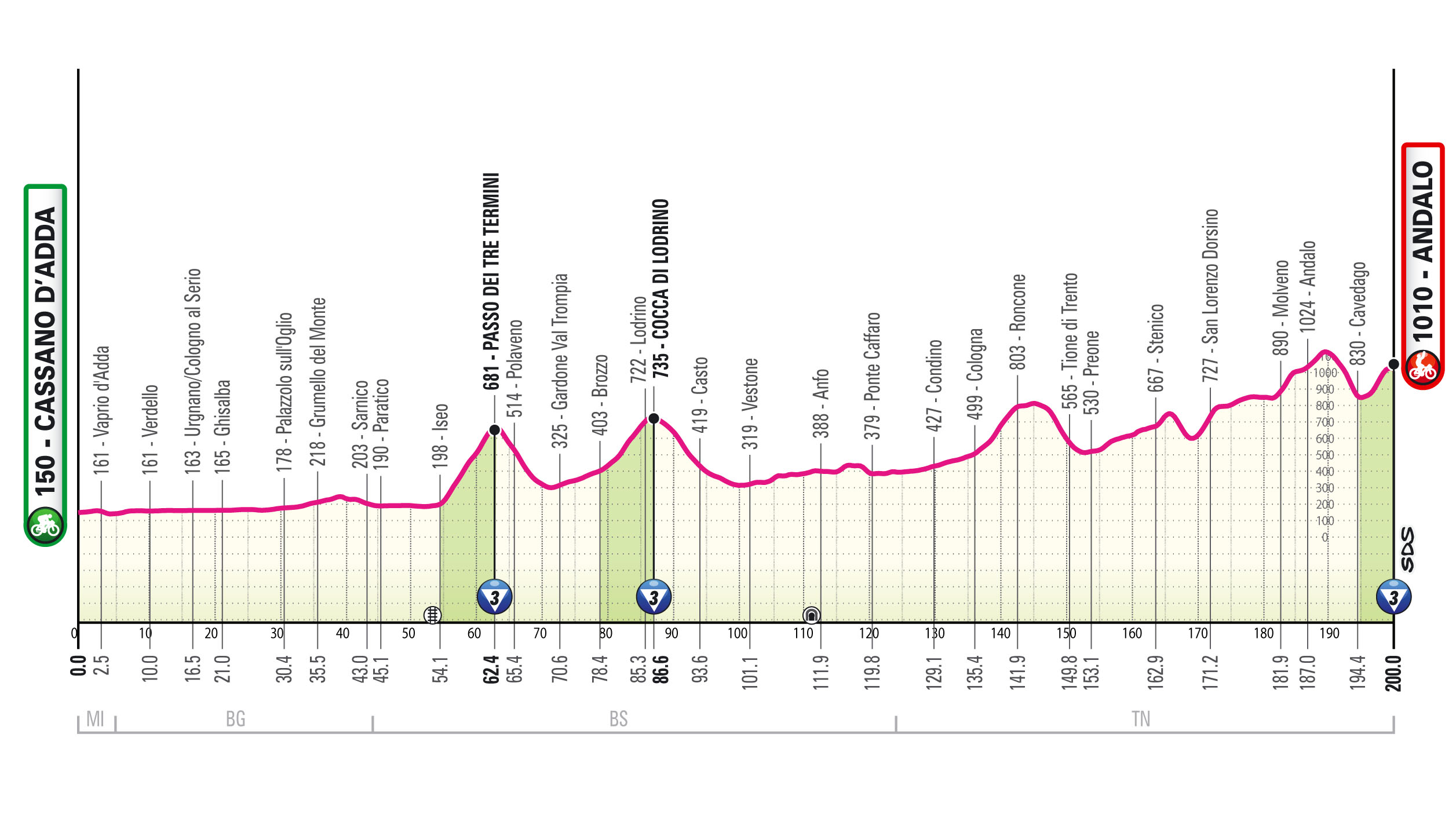

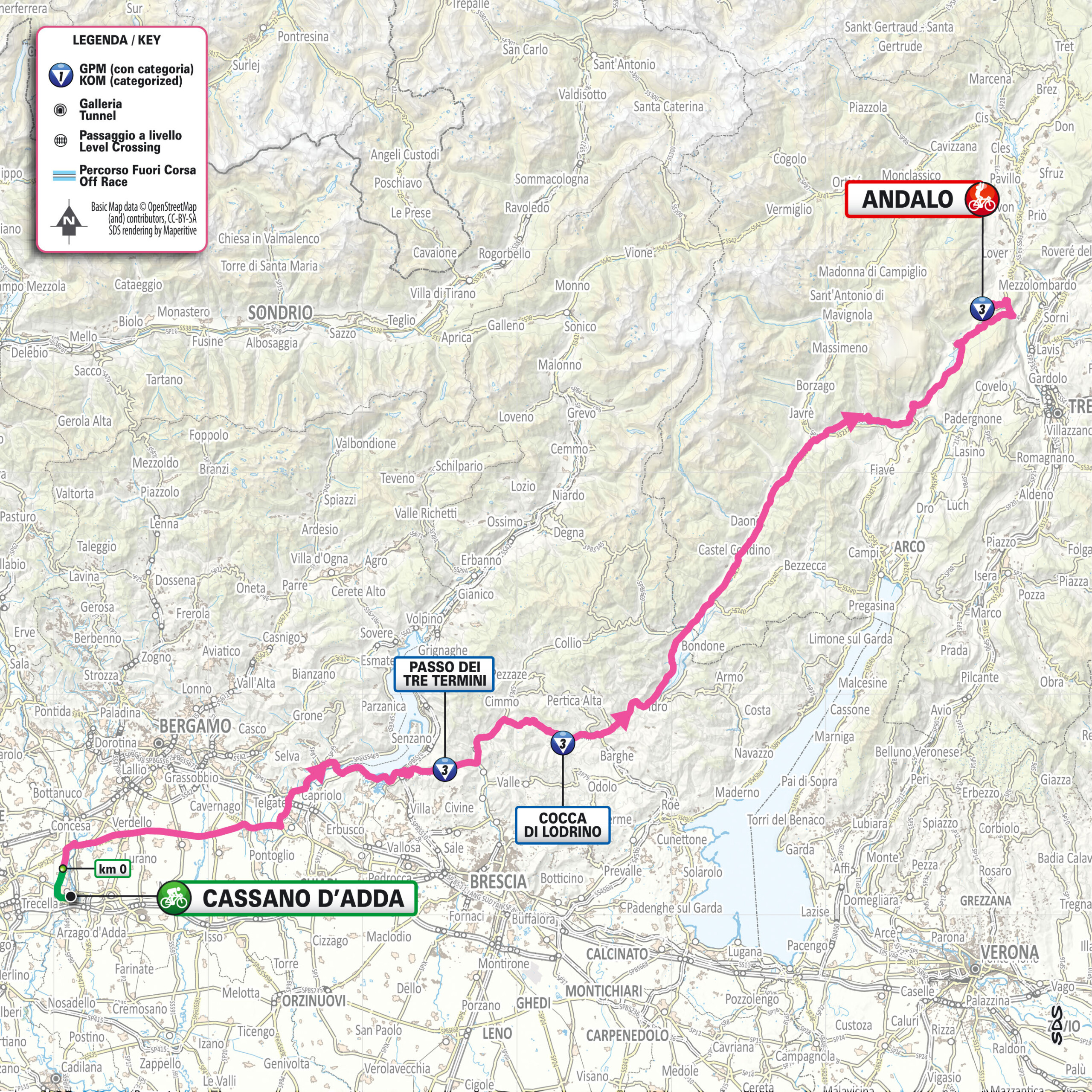

Stage 17 – Wednesday 27 May: Cassano d’Adda → Andalo

- Distance: 200 km

- Mountainous stage

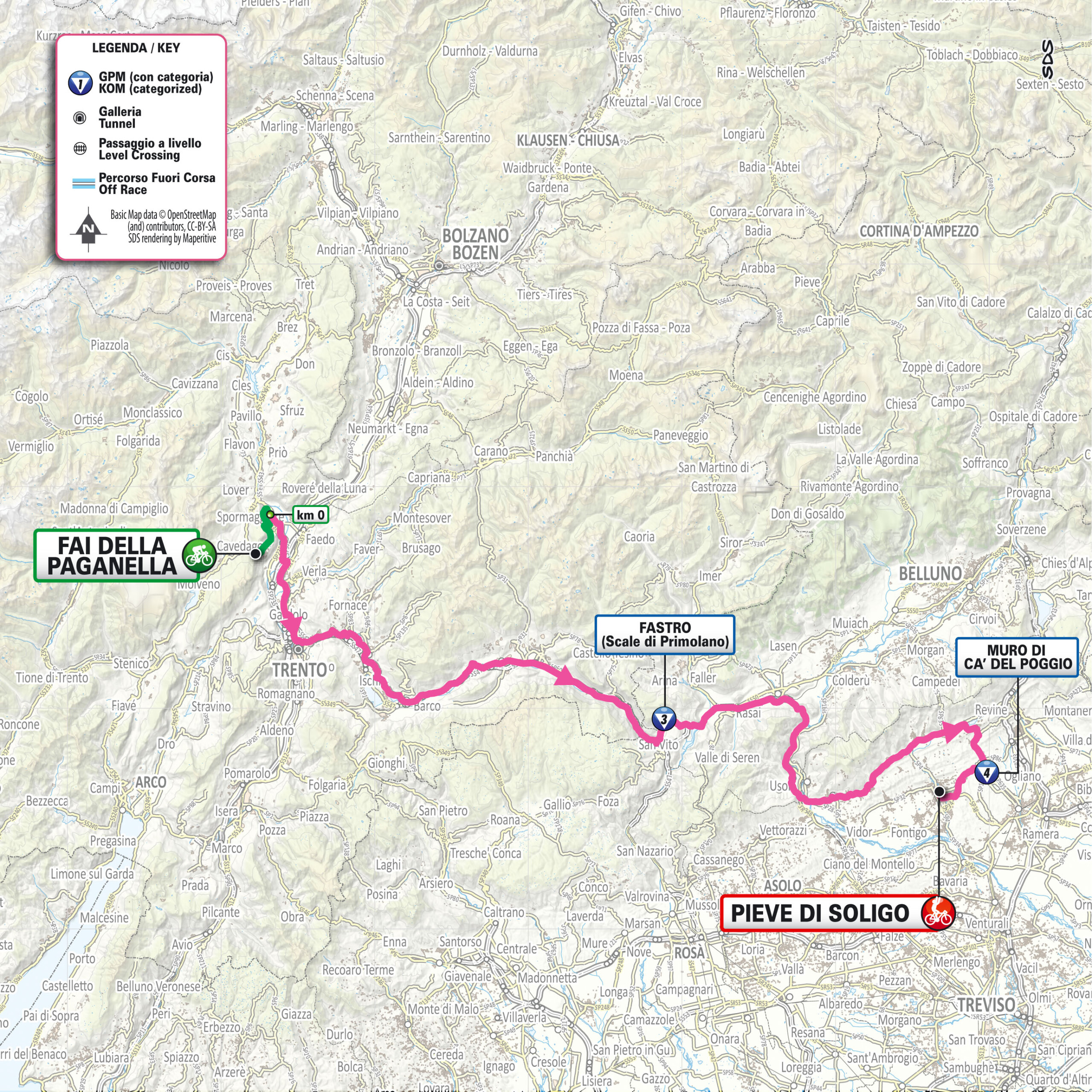

Stage 18 – Thursday 28 May: Fai della Paganella → Pieve di Soligo

- Distance: 167 km

- Mixed stage

Stage 19 – Friday 29 May: Feltre → Alleghe (Piani di Pezzè)

- Distance: 151 km

- Queen stage of the Giro

- Climbs: Duran, Staulanza (Coi variant), Giau (Cima Coppi, 2,233 m), Falzarego

Stage 20 – Saturday 30 May: Gemona del Friuli 1976–2026 → Piancavallo

- Distance: 199 km

- Two ascents of Piancavallo

- Commemorates 1976 Friuli earthquake

- Decisive for GC

Stage 21 – Sunday 31 May: Roma → Roma

- Distance: 131 km

- Traditional Grande Arrivo parade through the Eternal City

- Celebratory finish for all riders

#giroditalia

From Emilia Romagna to Piedmont: The Giro d’Italia Women 2026 Route Unveiled

ROMA, Italy (1 December 2025) — The Giro d’Italia Women 2026 will start in Cesenatico on 30 May and finish in Saluzzo on 7 June. Organised for the third consecutive year by RCS Sports & Events, the nine-stage race will cover 1,153.7 km with a total elevation gain of 12,500 metres. Two summit finishes await riders: Nevegal and Sestriere, which will feature the Colle delle Finestre for the first time in race history. RTL 102.5 will serve as the official radio station.

“The race will start on 30 May in Cesenatico and conclude with a grand finale on Sunday 7 June in Saluzzo, after nine stages – one more than in the previous two editions – totalling 1,153.7 km and 12,500 metres of elevation gain,” organisers confirmed at the presentation in Rome’s Auditorium Parco della Musica Ennio Morricone.

The event featured hosts Pierluigi Pardo and Barbara Pedrotti, with interviews conducted by Paolo Pacchioni of RTL 102.5. Sporting and entertainment stars attended, including Simon Yates, Elisa Longo Borghini, and two-time Giro winner Vincenzo Nibali. “We are thrilled to welcome these champions and all the fans of women’s cycling to experience this exciting route,” organisers said.

Italian and international authorities joined the ceremony. A Bulgarian delegation attended in person, while Italian officials sent video messages. Alessandro Onorato, Councillor for Major Events, Sport, Tourism and Fashion of Roma Capitale, presided over the presentation. RCS Group executives Urbano Cairo, Paolo Bellino, Mauro Vegni, and Stefano Barigelli also participated.

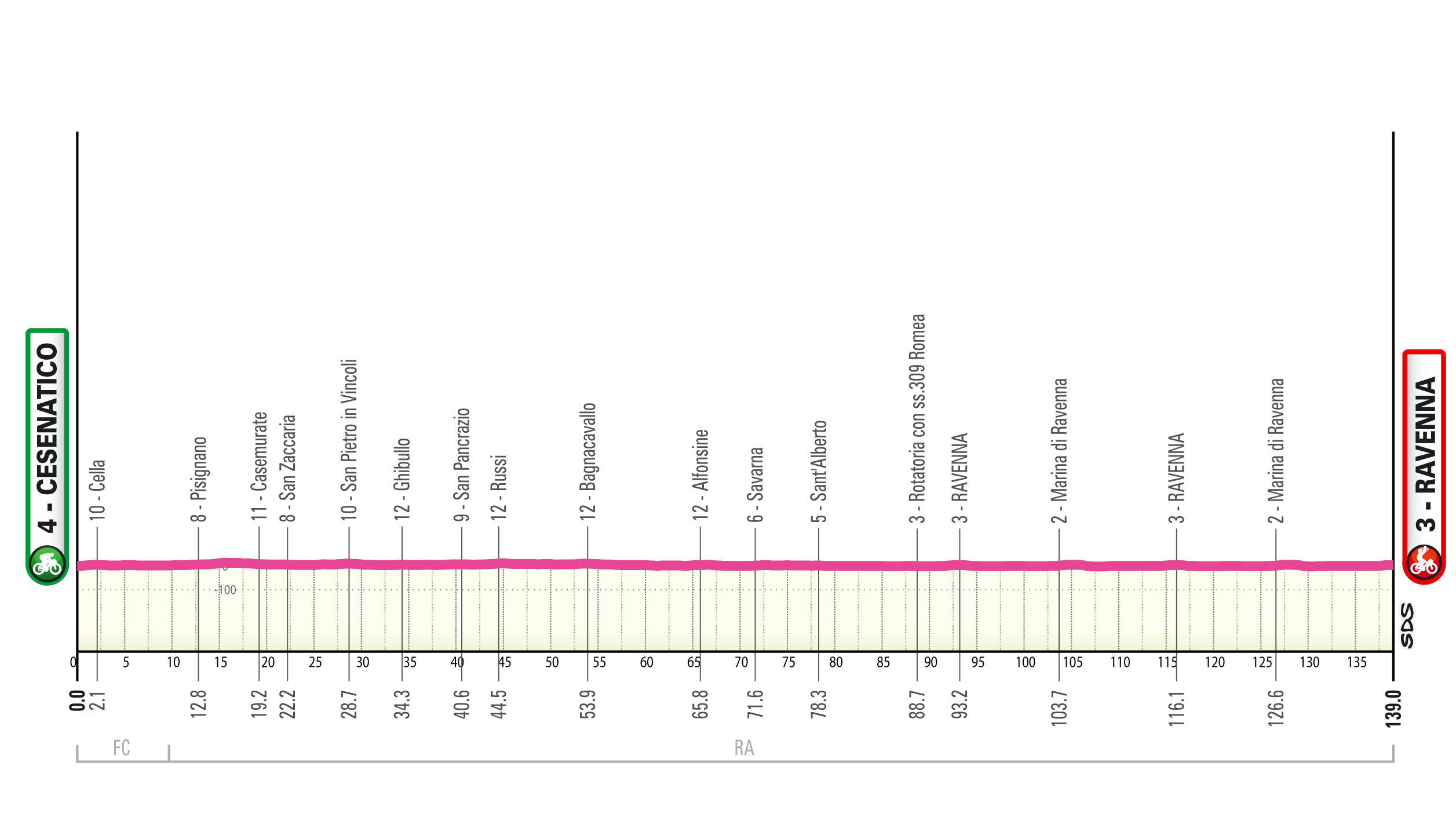

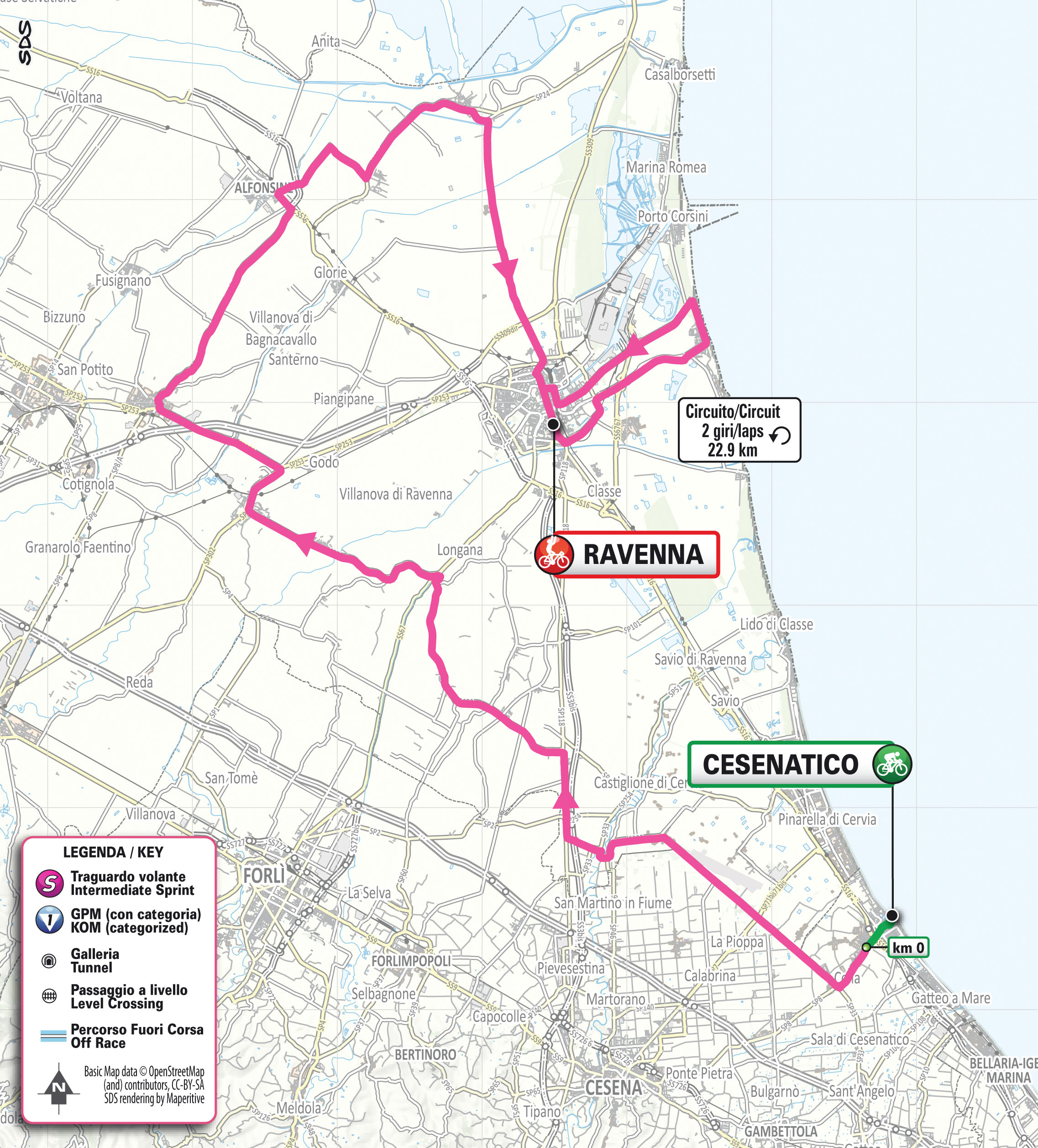

Stage 1: Cesenatico–Ravenna, 139 km

The Giro opens with a completely flat stage. Riders will start in Cesenatico, cross the Ravenna plain, skirt the Comacchio Valleys, and tackle two laps of a 23 km circuit before finishing in Ravenna.

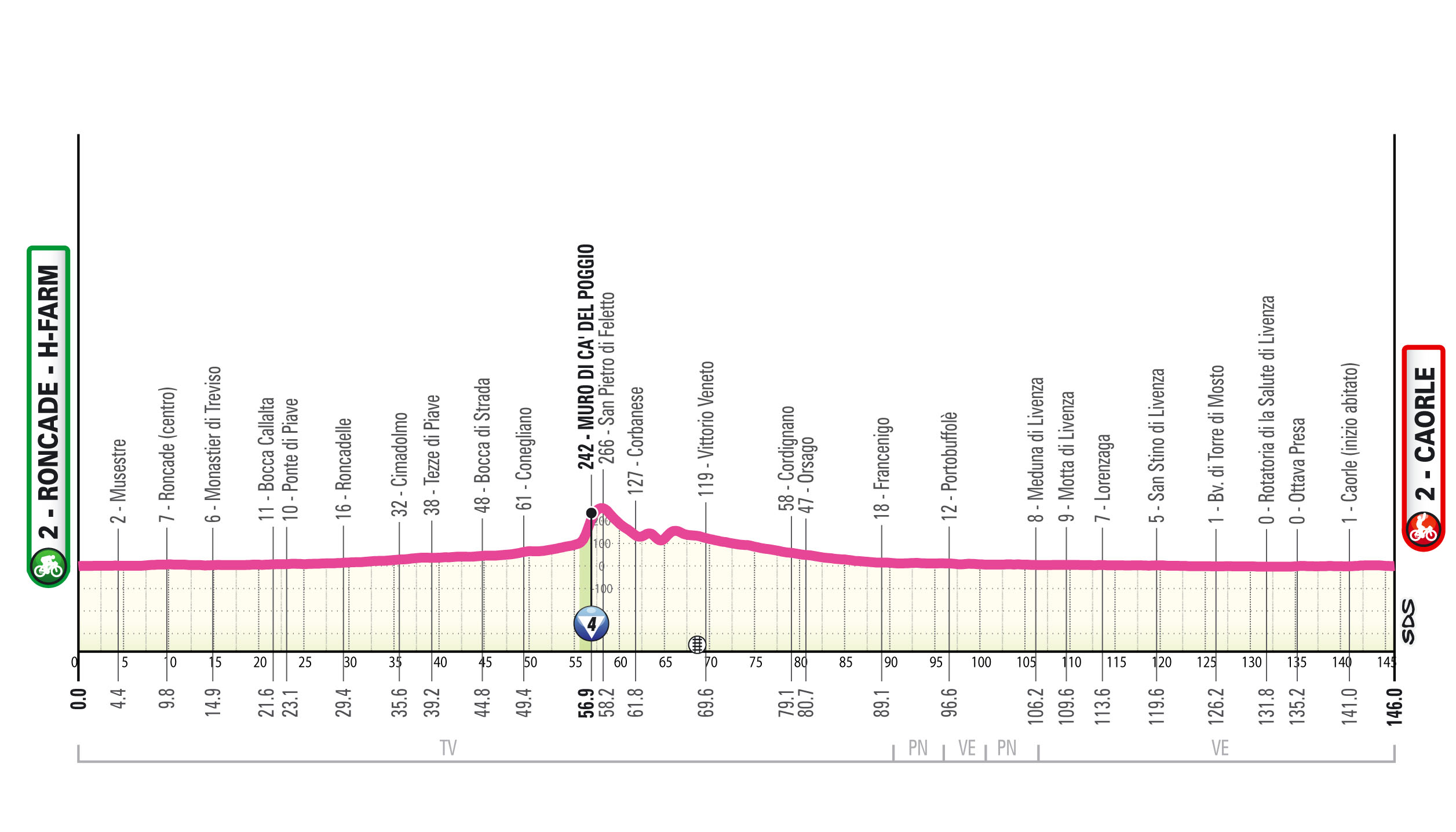

Stage 2: Roncade H-Farm–Caorle, 146 km

Stage 2 is almost entirely flat with a single intermediate climb. “The race starts from Roncade H-Farm, follows the Piave River, tackles the Muro di Ca’ del Poggio, then descends along the Livenza to the finish in Caorle,” organisers said. The profile will likely allow for a bunch sprint finish.

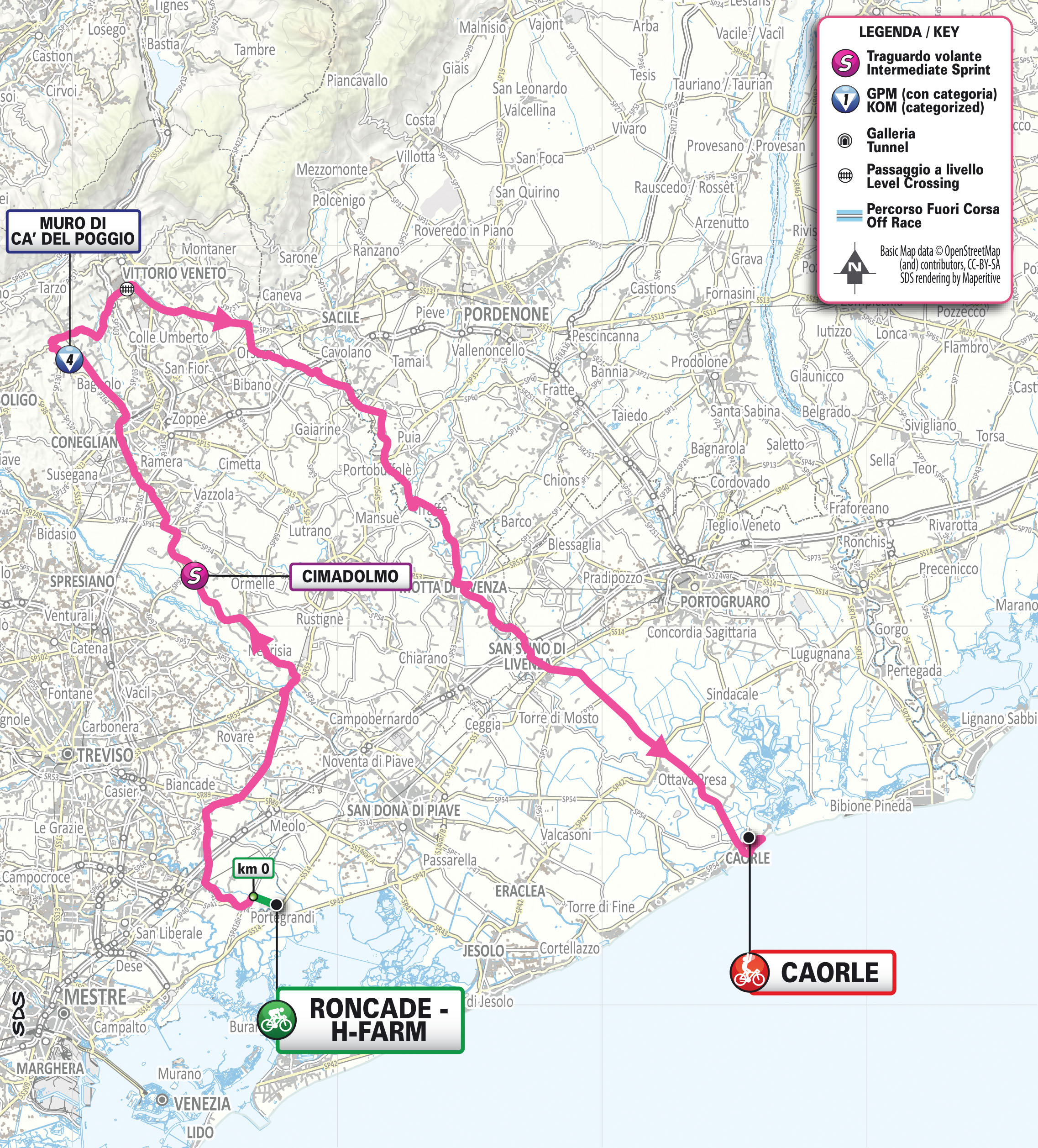

Stage 3: Bibione–Buja, 154 km

Riders face a flat start followed by a very undulating final circuit. The 36 km loop features several short, steep climbs, including Montenars, 18 km from the finish.

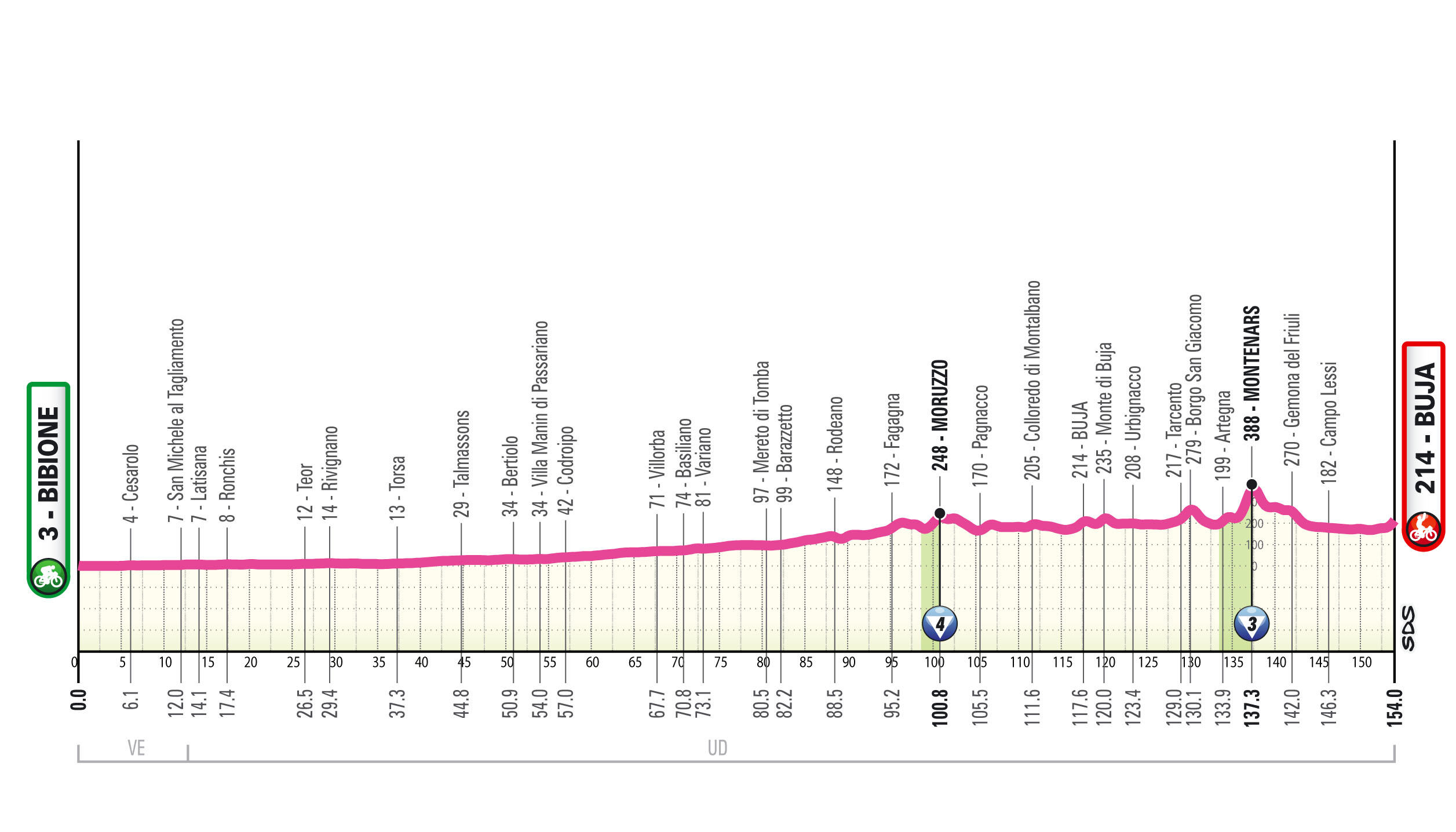

Stage 4: Belluno–Nevegal Tudor ITT, 12.7 km

Stage 4 presents a short, explosive mountain time trial. “A short descent leads out of Belluno, followed by a climb in three parts: about 3 km at 3% to the Caleipo intermediate split, then 4 km at over 10% with ramps up to 14%, and finally a less demanding 2 km section where full effort will be required to set a fast time,” organisers said. The route mirrors the 2011 Giro stage won by Alberto Contador.

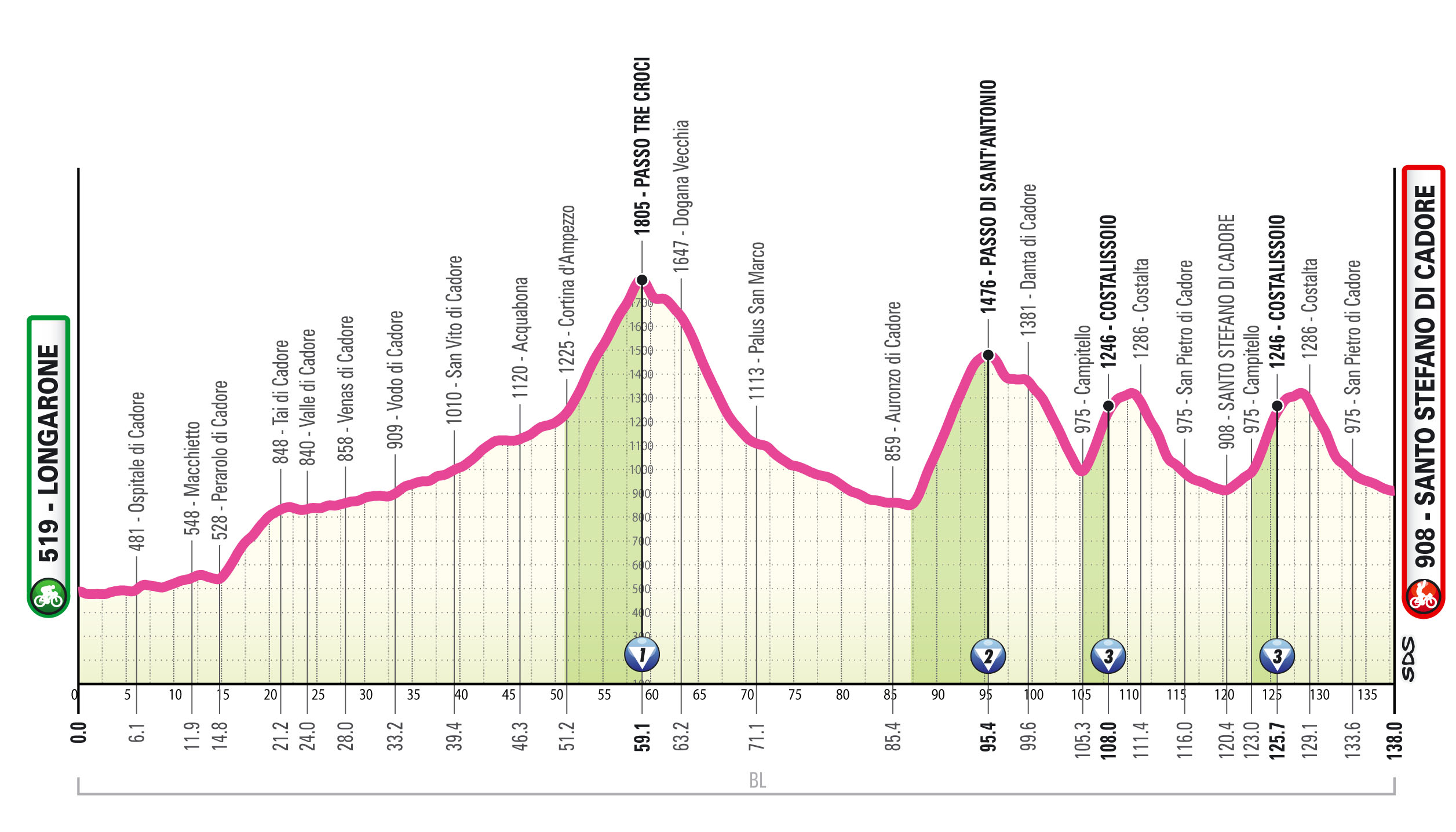

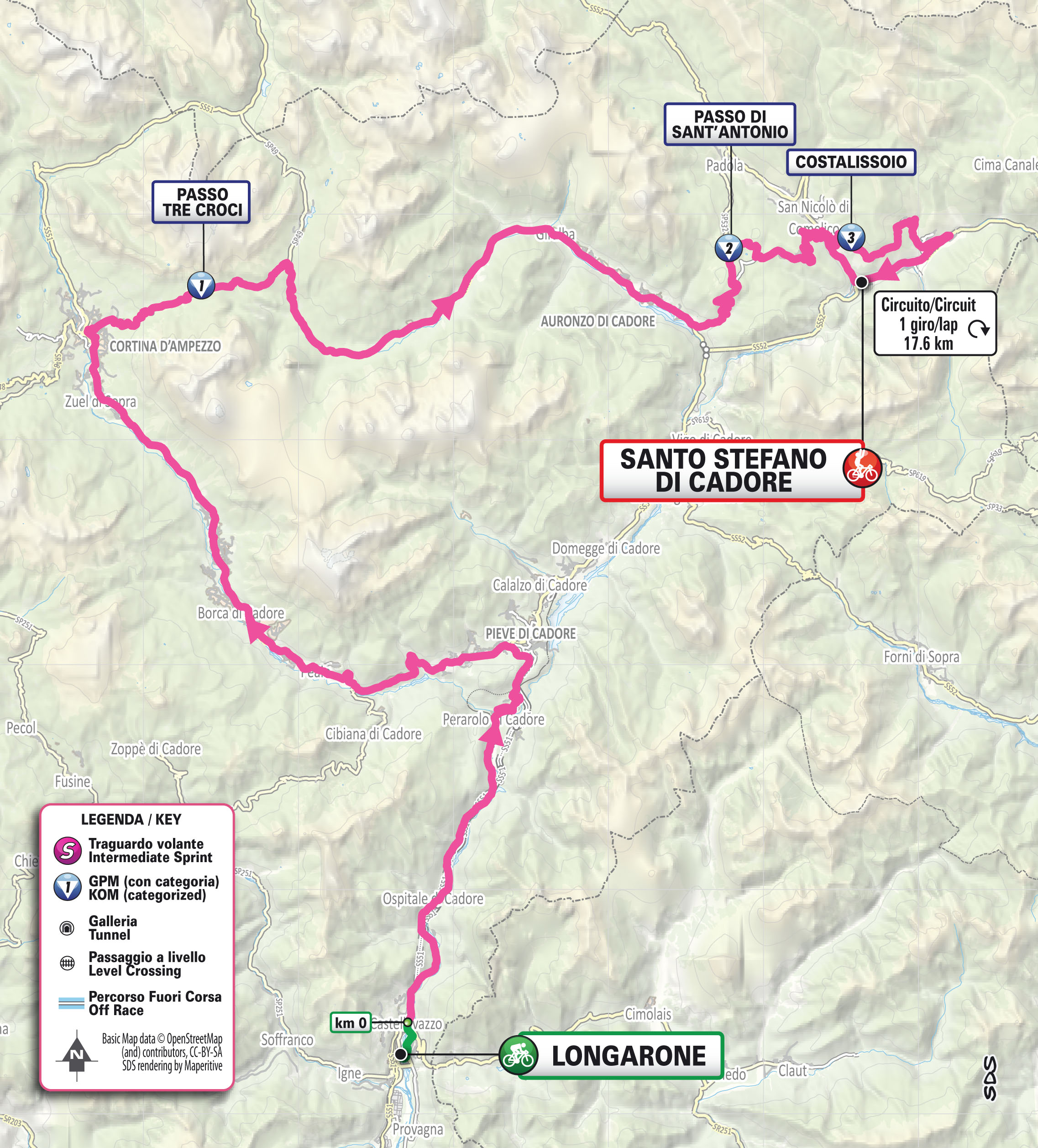

Stage 5: Longarone–Santo Stefano di Cadore, 138 km

Stage 5 takes riders into the Dolomites with four categorized climbs and no real recovery sections. “From Longarone the route climbs gently through the Piave Valley and the Boite Valley towards Cortina d’Ampezzo, then tackles the tough Passo Tre Croci and Passo di Sant’Antonio, which leads into the final circuit. Riders will climb Costalissoio, descend and pass under the finish line before climbing Costalissoio again to reach the finish,” organisers explained.

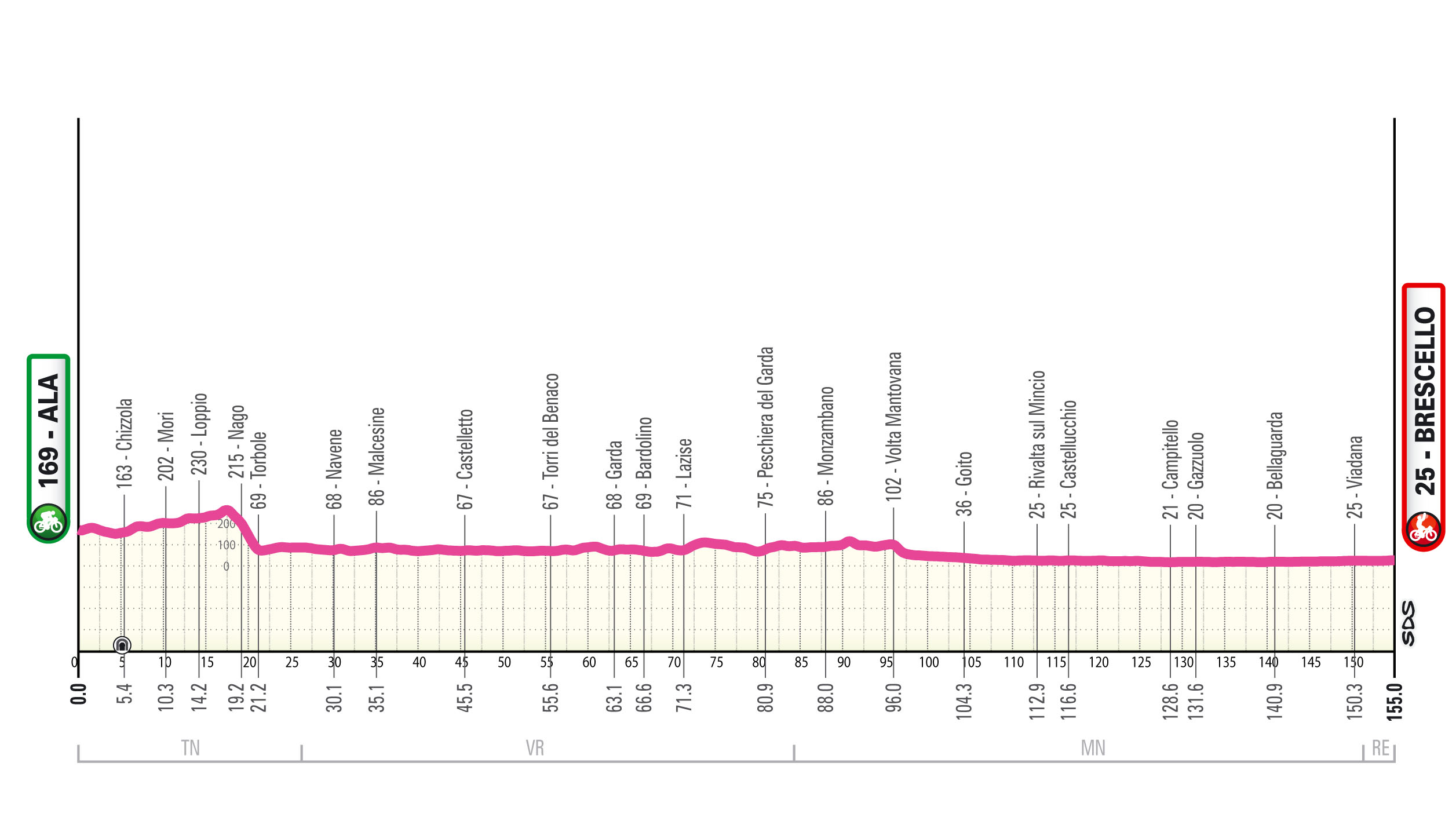

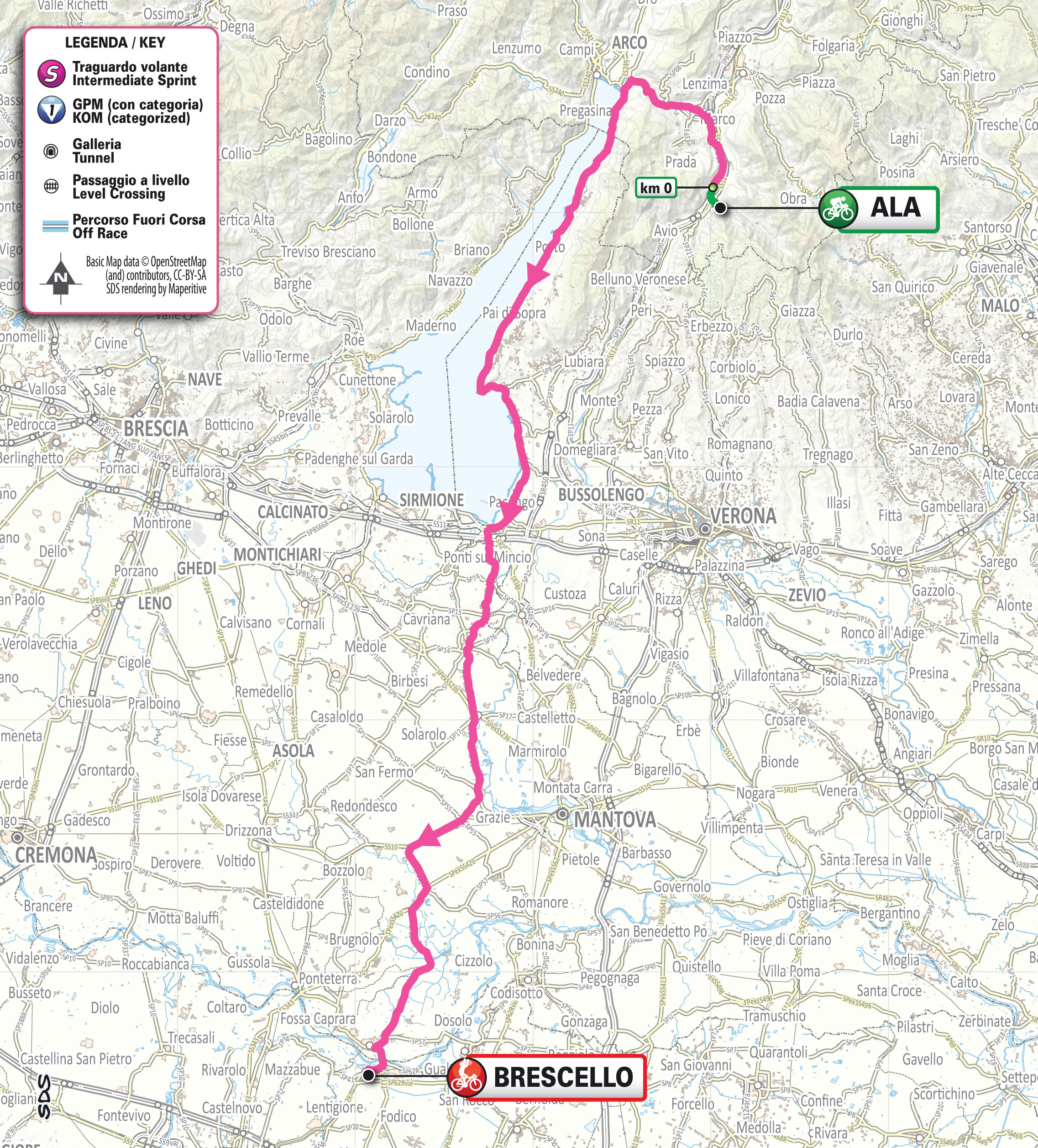

Stage 6: Ala–Brescello, 155 km

Stage 6 is likely to end in a bunch sprint. Riders will traverse the flat or slightly downhill section between the Adige River and Lake Garda, then cross the Verona and Mantua plains before crossing the Po shortly before the finish.

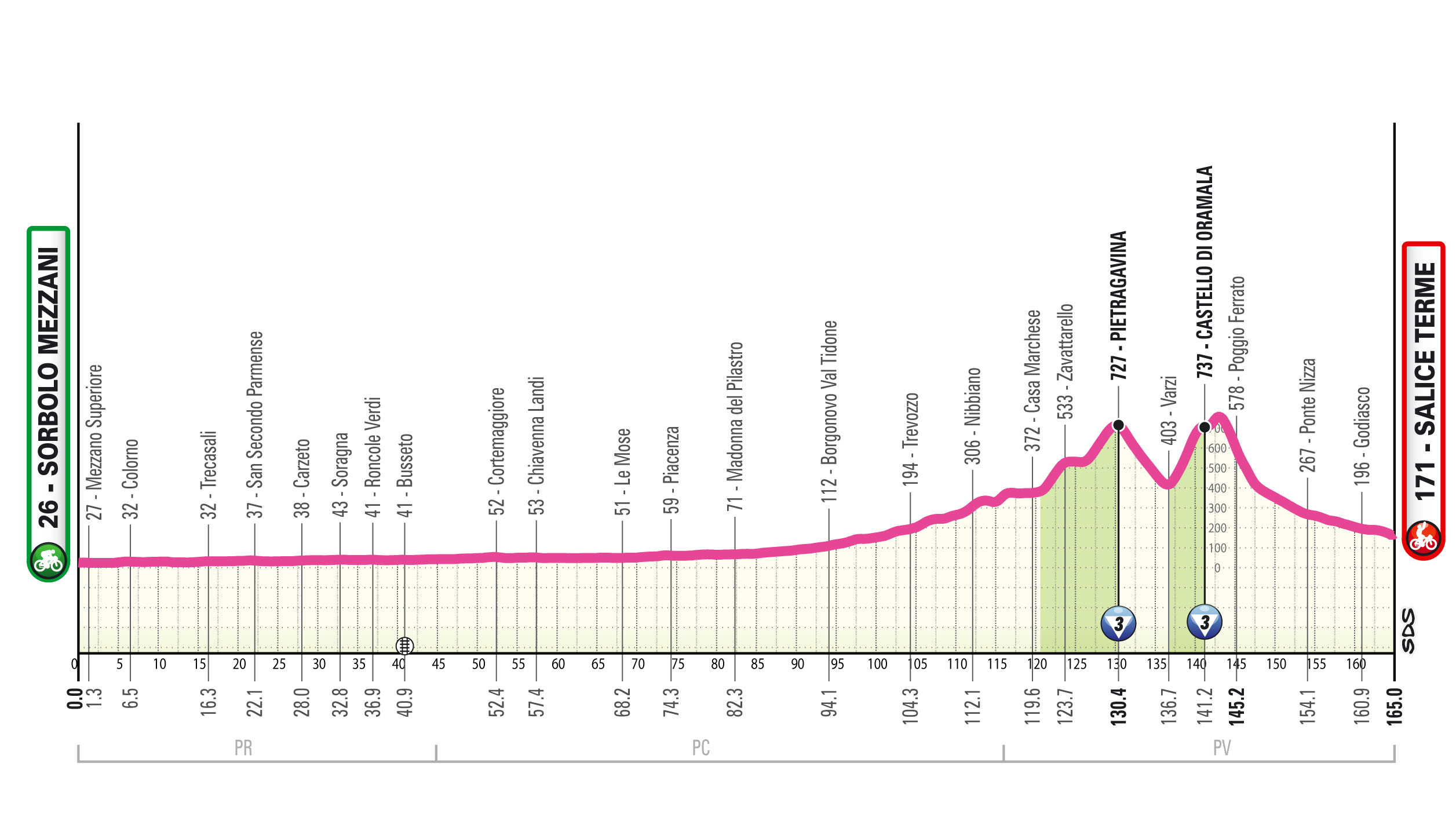

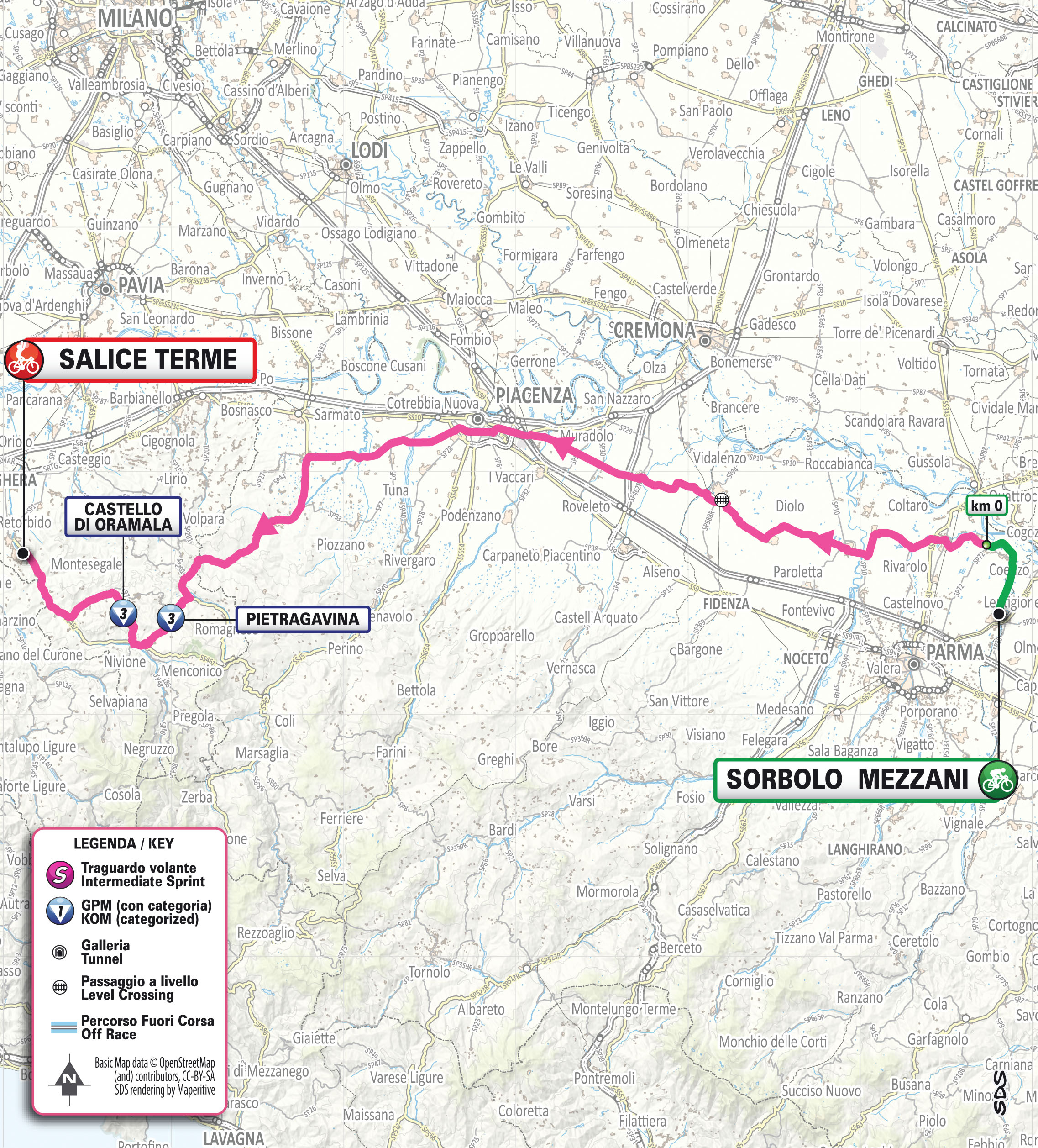

Stage 7: Sorbolo Mezzani–Salice Terme, 165 km

The longest stage of the Giro covers 165 km. Riders face a flat route up to Val Tidone, then tackle two short but steep climbs: Pietragavina and Castello di Oramala.

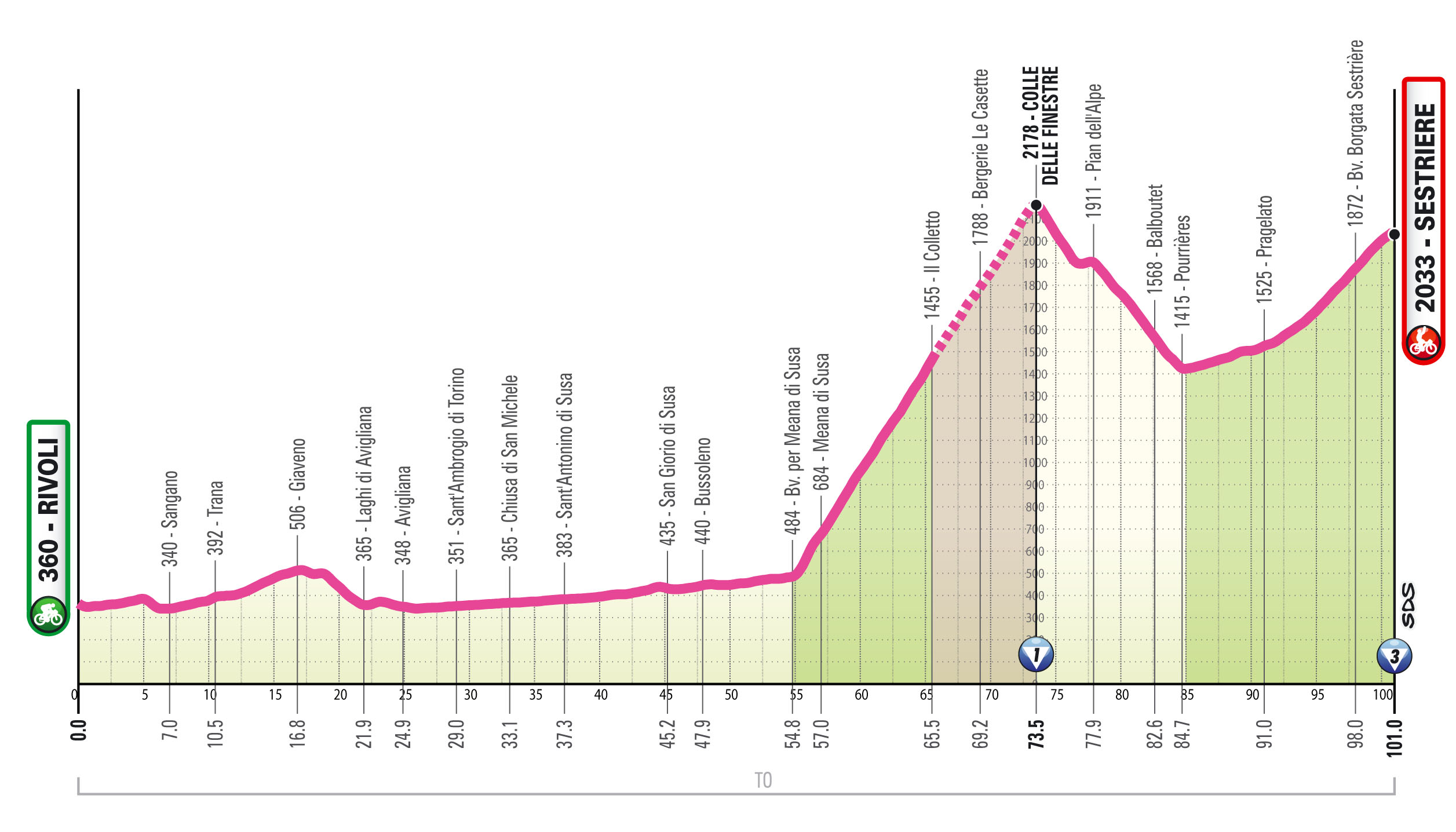

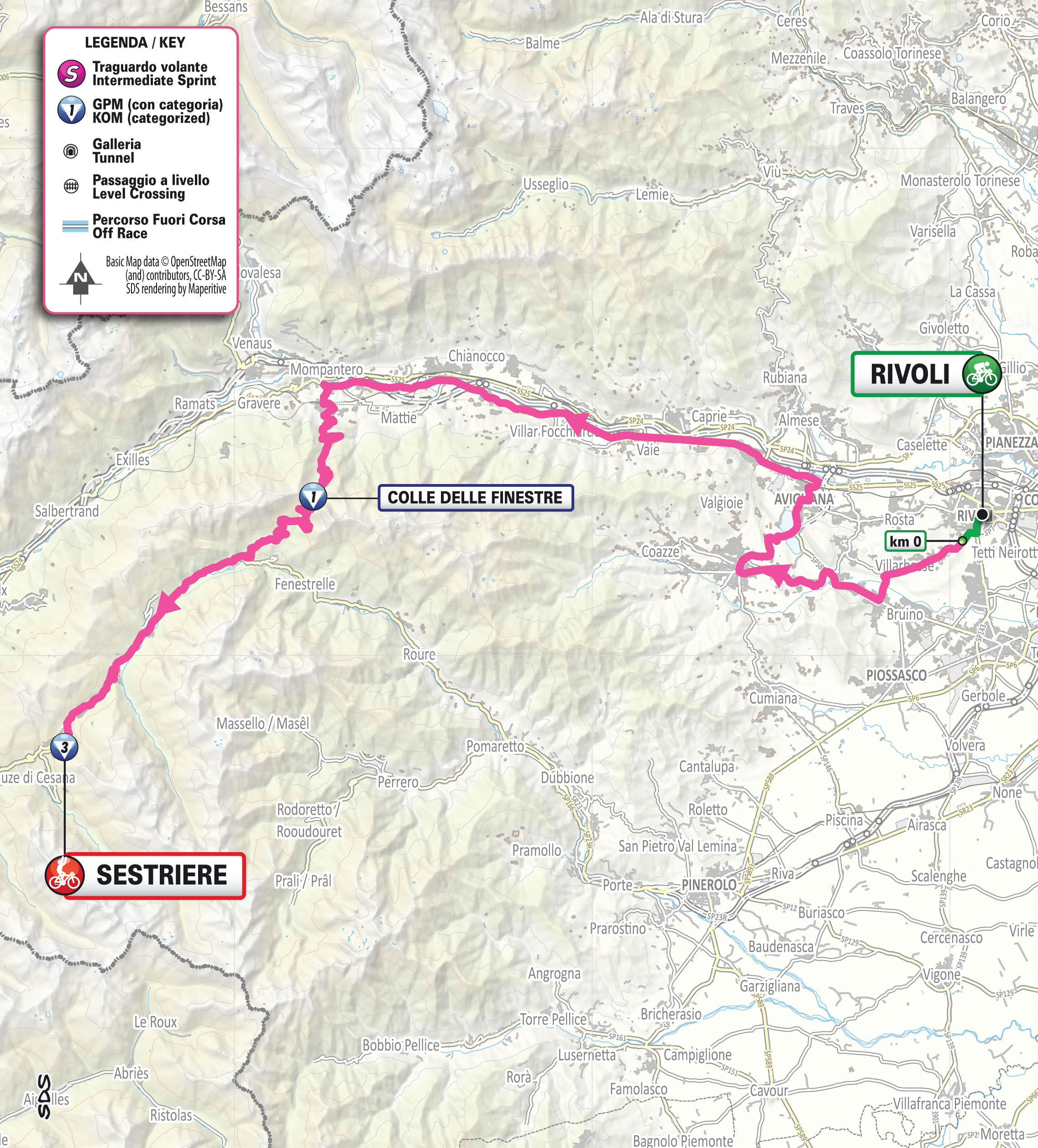

Stage 8: Rivoli–Sestriere, 101 km

The Queen Stage challenges riders with the Colle delle Finestre and the Colle del Sestriere. “The first 50 km are flat before the ascent: 18 km, half paved and half gravel, averaging around 9% with ramps up to 14% in the opening kilometres. A challenging descent follows, then the final climb, where all available power will be needed to make the difference,” organisers said.

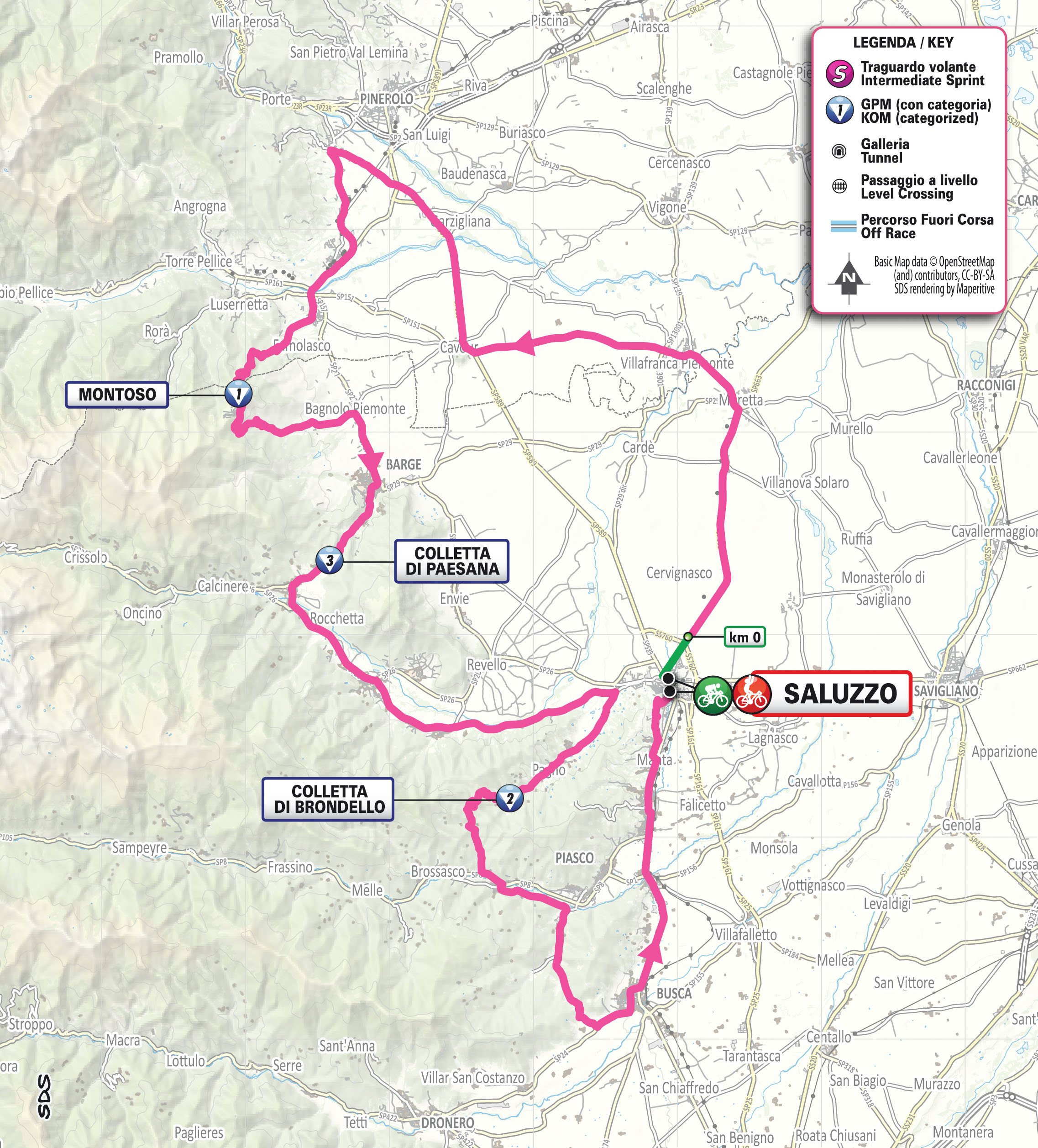

Stage 9: Saluzzo–Saluzzo, 143 km

The Giro concludes with a rolling stage. “The central section features three climbs in quick succession: Montoso, Colletta di Paesana and Colletta di Brondello. The finale is slightly downhill,” organisers noted.

#GirodItaliaWomen

CPSC urges immediate action on Rad Power Bikes batteries linked to 31 fires and $734,500 in property damage

WASHINGTON, D.C. (November 24, 2025) — The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission has issued an urgent warning urging consumers to immediately stop using certain lithium-ion batteries in Rad Power Bikes e-bikes after the Seattle-based company refused to agree to a formal recall.

The warning marks an unusual escalation in product safety enforcement, coming after Rad Power Bikes Inc. declined to participate in what the agency considered an acceptable recall program. The company cited financial constraints that it says would force it out of business.

“Given its financial situation, Rad Power Bikes has indicated to CPSC that it is unable to offer replacement batteries or refunds to all consumers,” the agency stated in its warning.

The Hazard

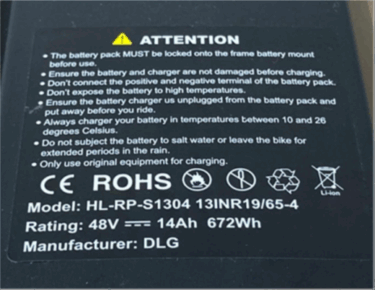

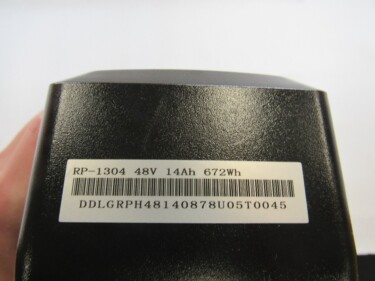

The CPSC warning covers lithium-ion batteries with model numbers RP-1304 and HL-RP-S1304. According to the agency, “the hazardous batteries can unexpectedly ignite and explode, posing a fire hazard to consumers, especially when the battery or the harness has been exposed to water and debris.”

The agency is aware of 31 reports of fire, including 12 reports of property damage totaling approximately $734,500. Particularly concerning to regulators: “Some of these incidents occurred when the battery was not charging, the product was not in use, and the product was in storage.”

The batteries were sold with nine Rad Power Bikes e-bike models: RadWagon 4, RadCity HS 4, RadRover High Step 5, RadCity Step Thru 3, RadRover Step Thru 1, RadRunner 2, RadRunner 1, RadRunner Plus, and RadExpand 5. They were also sold as replacement batteries.

Consumers can identify affected batteries by checking for the model number—HL-RP-S1304 or RP-1304—printed on a label on the back or rear of the battery.

Distribution and Sales

The batteries were sold on RadPowerBikes.com and at Best Buy stores and independent bike shops nationwide. Replacement batteries sold for approximately $550, while complete e-bikes with the batteries were priced between $1,500 and $2,000. The batteries were manufactured in China.

Company Response

In comments included with the CPSC warning at the company’s request, Rad Power Bikes stated: “Rad’s Safe Shield batteries and semi-integrated batteries are not subject to the agency’s statement. Rad had the batteries re-tested by third-party labs as part of this investigation; the batteries passed these tests again.”

The company said it proposed multiple solutions but was rebuffed. “Rad informed the agency that its demand to replace all batteries, regardless of condition, would immediately put Rad out of business, which would be of no benefit to our riders,” the statement said. “Rad is disappointed that it could not reach a resolution that best serves our riders and the industry at large.”

The company advised customers to “inspect batteries before use or charging and immediately stop using batteries that show signs of damage, water ingress, or corrosion, and to contact Rad so we can support our riders.”

Detailed Company Statement

In a separate response published on its website, Rad Power Bikes offered a more extensive defense, stating it “firmly stands behind our batteries and our reputation as leaders in the ebike industry, and strongly disagrees with the CPSC’s characterization of certain Rad batteries as defective or unsafe.”

The company emphasized its compliance record: “We have a long and well-documented track record of building safe, reliable ebikes equipped with batteries that meet or exceed rigorous international safety standards, including UL-2271 and UL-2849. The CPSC proposed requiring these UL standards in January 2025, but has yet to adopt them. Rad ebikes have met these standards for years.”

Rad Power Bikes said that “reputable, independent third-party labs tested Rad’s batteries, both as part of our typical product testing and again during the CPSC investigation, and confirmed compliance with the highest industry standards. Our understanding is that the CPSC does not dispute the conclusions of these tests. It is also our understanding that the battery itself was not independently examined per industry-accepted test standards.”

Incident Rate and Context

The company characterized the problem in terms of scale: “The incident rate associated with the batteries in the CPSC’s notice is a fraction of one percent. While that number is low, we know even one incident is one too many, and we are heartbroken by any report involving our products.”

Rad Power Bikes argued that battery fire risks exist across industries: “It is also widely understood that all lithium-ion batteries—whether in ebikes, e-scooters, laptops, or power tools—can pose a fire risk if damaged, improperly charged, exposed to excess moisture, subjected to extreme temperatures or improper modifications to the electrical components, all of which Rad repeatedly advises against in user manuals and customer safety guides.”

The company disputed the CPSC’s characterization of the water exposure hazard: “Contrary to the CPSC’s statement, mere exposure to water and debris does not create a hazard; rather, significant water exposure, as warned against in our manuals, can pose a hazard.”

The company added: “These risks apply across industries and exist even in products that are fully UL compliant. Ebike batteries are significantly more powerful than household device batteries, which is why proper care and maintenance are so important and why Rad continues to invest in rider education and safety innovation.”

Failed Negotiations

According to Rad Power Bikes, the company attempted to find a compromise. “Rad offered multiple good-faith solutions to address the agency’s concerns, including offering consumers an opportunity to upgrade to Safe Shield batteries (described below) at a substantial discount. CPSC rejected this opportunity,” the company stated.

The company said the financial burden would be insurmountable: “The significant cost of the all-or-nothing demand would force Rad to shut its doors immediately, leaving no way to support our riders or our employees.”

Safety Innovation Defense

The company defended its development of newer battery technology as evidence of commitment to safety, not an admission that older products were defective. “Rad has been a pioneer in promoting and advancing energy-efficient transportation, and our efforts to innovate and build safer, better batteries led to the development of the Rad Safe Shield battery. However, a product that incorporates new, safer, and better technology does not thereby mean that preceding products are not safe or defective.”

Rad Power Bikes drew an analogy: “For example, when anti-lock brakes were developed, that did not render earlier cars unsafe; it simply meant a better, safer technology was available to consumers.”

The company concluded: “That kind of thinking discourages innovation and limits the accessibility that ebikes bring to millions of people. Without the adoption of clear, common-sense standards, no electric bike manufacturer can operate with confidence.”

What Consumers Should Do

The CPSC is urging consumers to take immediate action: “CPSC urges consumers to immediately remove the battery from the e-bike and dispose of the battery following local hazardous waste disposal procedures. Do not sell or give away these hazardous batteries.”

The agency provided specific disposal instructions: “Do not throw this lithium-ion battery or device in the trash, the general recycling stream (e.g., street-level or curbside recycling bins) or used battery recycling boxes found at various retail and home improvement stores. Hazardous lithium-ion batteries must be disposed of differently than other batteries because they present a greater risk of fire.”

Consumers should contact their municipal household hazardous waste collection center before bringing batteries for disposal. “Before taking your battery or device to a HHW collection center, contact it ahead of time and ask whether it accepts hazardous lithium-ion batteries. If it does not, contact your municipality for further guidance,” the agency advised.

Regulatory Action

The CPSC stated it “is issuing this public health and safety finding to expedite public warning about this product because individuals may be in danger from this product hazard.”

The product safety warning is numbered 26-118 and is available at cpsc.gov.

Bike Safety Programs Target Rural Southeast Idaho Communities

(November 25, 2025) — A four-organization partnership will deliver bicycle safety and wellness programs to rural families across seven Southeast Idaho counties.

The Southeast Idaho Council of Governments, Idaho Walk Bike Alliance, Southeast Idaho Safe Routes to Schools, and Cowboy Ted’s Foundation for Kids signed a Memorandum of Understanding to bring programs to Bannock, Bear River, Bingham, Caribou, Franklin, Oneida, and Power counties.

Rural communities often get overlooked for wellness and bike safety programs, according to “Cowboy” Ted Hallisey. The partnership makes rural areas its priority.

“We plan to offer programs and biking activities that will be fun and familiar for rural kids and communities,” Hallisey said.

Programs include Safe Routes to Schools initiatives, bike rodeos, human-powered rodeo activities, wellness assemblies, and customized transportation activities. The organizations will host events at schools, libraries, fairs, and community gatherings.

Hallisey, who grew up in a rural community, designed the activities to keep rural kids comfortable while learning safety and wellness skills through bicycling.

Schools, officials, libraries, preschools, community groups, and 4-H organizations can schedule events by contacting SICOG or Hallisey at (208) 870-1633 or [email protected].

Activities include wellness assemblies, human-powered rodeos with bike courses featuring keyhole and barrel racing, color fun runs, and reading sessions with Hallisey’s children’s books.

Beyond the Hiawatha: Discovering Idaho’s Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes

By Gail Newbold — Mention that you’re going cycling in northern Idaho and everyone assumes you’re biking the infamous Route of the Hiawatha renowned for its 10 tunnels and seven train trestles through breathtaking mountain scenery.

Tell them instead that you’re hitting the 73-mile paved Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes and watch them draw a blank; even though it’s one of the most spectacular trails in the western United States that spans the Idaho panhandle between Mullan and Plummer.

Place it atop your cycling bucket list but don’t knock off the Trail of the Hiawatha. Each ride is outstanding and in the Rail-to-Trail Conservancy’s Hall of Fame. If you’re in the area, do both.

However, since this article focuses on the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes, here are a few benefits you won’t get on the Hiawatha. The Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes is:

- longer by 58 miles.

- sizably less crowded.

- free.

- paved.

- easy to access with 20 developed trailheads providing entry points, and 20 scenic waysides with tables to stop for a picnic or a short rest.

- wonderfully diverse.

- well-equipped with restrooms.

Given its length, many cyclists bite off one section of the trail at a time. It’s easy to do using one of the many trail maps online and choosing your start and stop points. You can enjoy an out-and-back ride on a section, or tackle more miles and use a shuttle service to transport you and your bike back to your car.

Opinions vary on which section is the prettiest, assuming you don’t have time to ride all 73 miles. My vote is the 34-mile section between Harrison and the Pinehurst Trailhead. The Cycle Haus in Harrison has its own opinion on the topic that you can read online at thecyclehaus.com/trail-of-the-coeur-d-alenes. The shop’s trail guide is extremely helpful when planning your route and includes detailed descriptions of every section of the trail and each trailhead with rankings for each. It gives information about restrooms, amount of parking, picnic tables, views, type of scenery and terrain, natural beauty, wildlife and more.

Historically, the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes began as a railroad line serving the Silver Valley mining industry before being converted to a recreational trail in 2004. It has a 1,200-foot elevation change, most of that on both ends of the trail. The rest is primarily flat and spans almost the entire Idaho Panhandle from the border of Montana in the east and Washington in the west.

Unlike some trails where the scenery can become mind-numbingly monotonous, the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes serves up an endless mix of wetlands, rivers, lakes, mountains, pines, a few bridges and historic mining towns. Breathe deep and enjoy the scents along with the landscape.

34 Miles from Harrison to Pinehurst

We plucked out the prime midsection of the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes for our ride, starting in Harrison and ending at the Pinehurst Trailhead. The reason was I’d already cycled the end from Plummer to Harrison on a previous trip, and frankly, didn’t think it was extraordinary. I skipped the opposite end of the trail from Mullan to Pinehurst because it runs alongside Interstate 90 with noticeable road noise and through industrial zones. If you also opt to skip the latter section, be sure to visit Wallace by car — one of my favorite historic mining towns set against a backdrop of pines.

The 60-minute drive from our lodging in Coeur d’Alene along the Lake Coeur d’Alene Scenic Byway to Harrison was a stunning way to start the day. The Harrison trailhead has restrooms and picnic tables and is located next to Harrison City Beach — a great spot to cool off.

We hit the trail at 10 a.m. on a bluebird day in August with sunshine and temperatures in the low 70s. I was excited but also terrified about the possibility of encountering a moose. My husband, on the other hand, was desperate to see one, encouraged by trail descriptions promising frequent moose sightings and advice on what to do if one blocked the trail.

The first 10.5 miles from Harrison to Medimont run through the heart of the Chain Lake region past seven lakes, wetlands, streams and the Coeur d’Alene River. Almost immediately I was snapping photos of a beaver lodge and gorgeous pink water lilies covering the surface of the water.

The lone blemish was a mile or so of scarred landscape and construction equipment tied to the Grays Meadow Restoration project with the goal of cleaning up mining pollution, reducing flood risk, and preserving the valley’s beauty.

Just before reaching the Medimont Trailhead, we passed a stunning stretch of wetlands home to countless grebes, elegant waterbirds often likened to flamingos, and then beautiful Cave Lake. Picnic tables and benches on the cool banks of the lake offer a cool respite. It was a stunning section of trail, and I was grateful we didn’t surprise anything more than a cute covey of quail.

Cyclists Amanda and Dave Sheets from Virginia were also taking advantage of the pretty trailhead. They said they were on a three-week cycling trip that had included the Great Miami River Trail in Ohio, the Elroy-Sparta State Trail in Wisconsin, and the George S. Mickelson Trail in South Dakota where they fought crowds of motorcyclists at Sturgis. They biked the Route of the Hiawatha the day before and rated the scenery 10 out 10, but were disappointed by the crowds and a 40-minute wait for the shuttle back to the start. Their next cycling adventure was the Paul Bunyan State Trail in Minnesota.

“Of the trails we’ve been on so far, the Trail of the Coeur reminds me most of the Mickelson Trail because it’s easy to ride, mostly flat and has lots of beautiful scenery,” Amanda said. She was excited they’d seen snakes, deer, red tailed hawks, blue herons, geese and more on the trail.

We also met a couple from Park City, Utah, who also cycled the Route of the Hiawatha a few days prior and were surprised at how crowded it was on a weekday in August.

By contrast, the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes was surprisingly uncrowded. For long stretches, we saw no one. The cyclists we passed were a mix of families, older couples, and solo riders. We only passed one set of elite-looking cyclists clad in kits, hunched over their handlebars, and riding fluidly in sync.

If You Go

- The Cycle Haus in Harrison offers shuttle services and bike rentals. There are private shuttle services available as well. We hired Rick’s Bicycle Shuttle Service (208-446-4006) and were very pleased. Rick was already at the Pinehurst Trailhead when we showed up 20 minutes early. We loved Rick, a chatty former educator and lifetime resident of Harrison, who dispensed a wealth of information upon booking and during the ride to our car. He charges by number of miles. The drive from Pinehurst to Harrison cost us $120.

- If you don’t plan to bring your own food or are worried about running out of water, check Cycle Haus’s trail map (visitnorthidaho.com/activity/trail-of-the-coeur-dalenes) for towns along the route with food and water. Rick recommended The Snake Pit across from the Enaville trailhead and the Timbers Roadhouse across from the Cataldo Trailhead. The town of Wallace has many food options.

- Another gorgeous trail in the area to ride if you have time is the North Idaho Centennial Trail that runs along the Spokane River and Lake Coeur d’Alene. It extends from the Idaho-Washington state line to Higgins Point, with scenic views, restrooms, charming parks and long stretches of beach.

- For more information, see: https://parksandrecreation.idaho.gov/state-park/trail-of-the-coeur-dalenes/

Cycling Casualties Continue to Increase; Alcohol a Factor

By Charles Pekow — Cyclist casualties saw a sharp increase in 2023. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) released its final figures for the year, reporting that cyclist fatalities rose by 4 percent compared to 2022, while injuries climbed by 8 percent.

NHTSA recorded 1,166 cyclist deaths in 2023, representing 2.9 percent of all traffic fatalities, up from 1,117 in 2022. The agency also estimated 49,989 cyclists were injured, compared with 46,195 the previous year.

The death rate for male cyclists was more than seven times higher than for females, and the injury rate was five times higher. Alcohol was a factor in many cases: in 34 percent of fatal crashes, either the cyclist or the driver had been drinking, and 22 percent of deceased cyclists had alcohol in their system.

Most of the fatalities—81 percent—occurred in urban areas.

The NHTSA figures apply to “pedalcycles,” a category that includes traditional bicycles, e-bikes, unicycles, and tricycles. Full data is available at: https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/813739

Davis Phinney and the Swan Song of the Coors Classic

By Dave Campbell — From 1975 through 1988, the premier American cycling event was the Coors International Bicycle Classic. Initially, it was a weekend event held in and around Boulder, Colorado, known as the Red Zinger and sponsored by the Celestial Seasonings tea company. Both paralleling and stimulating explosive growth in American cycling, the event seemed to get bigger and better every year. By 1978 the race was the premier women’s event in the world, became the Coors Classic in 1980 with an ensuing bump in sponsorship dollars, and by 1983 it was ten stages long and had expanded into neighboring Wyoming. In 1984 the event was the key pre-Olympic tune-up for most of the world’s amateur National Teams coming to race in the LA Olympics. The 1985 event expanded to two weeks and traveled from California and across Nevada before ending with the now well-known Colorado stages. 1985 also saw La Vie Claire, the best professional team in the world, take part with the two best riders in the world—Bernard Hinault and Greg LeMond. LeMond’s overall win added even more luster to the prestige of the race. By the following year, nearly all the best riders in the world were at the Coors, using it as their final preparation for the World Championships in Colorado Springs. This time Hinault triumphed, and many called it the fourth most prestigious stage race in the world.

In 1987, however, race promoter Michael Aisner finally had an unlucky year and, in Hollywood parlance, “jumped the shark.” He expanded the race again, this time starting the men in Hawaii. The extra expenses and lack of sponsorship meant the best European riders stayed home, and only 59 riders competed in the sixteen-stage event, while the women’s event maintained its status with ten stages in Colorado. By 1988 Coors passed on the automatic renewal option, and the event took on a last-minute amateur sanction to cut expenses. Many worried that the end of America’s flagship event was near. Ultimately, 77 men (25 pros and the rest amateurs) took the start in San Francisco in mid-August for a fourteen-day event featuring 1,077 miles and nearly 60,000 feet of climbing.

Davis Phinney discovered the sport of cycling when he saw the event pass by his house in 1975 and, by 1988, he was racing in his eleventh edition. Phinney had become synonymous with the Classic and had won the points jersey every year since 1981, as well as taking a record fourteen stages, but his best overall placing was ninth. He was, after all, primarily a sprinter, and the Coors involved major climbing. He suffered a horrendous crash in April of 1988 when he smashed into the back of a team car while attempting to chase back to the peloton in a Belgian Classic. He broke his nose, severed a muscle in his arm, and ultimately required 150 stitches, mostly to his face. Undeterred, he was back on his bike in a few days, racing again in ten, and winning within a month. In May he helped his 7-Eleven teammate Andy Hampsten win a historic Giro d’Italia, and in July he finished his first Tour de France, notching four top-five sprint finishes and ultimately ending second in the points competition. He hadn’t finished a Grand Tour since 1985, let alone two, and he finished strongly, notching fifth in the final charge up the Champs-Élysées. He was, quite simply, in the best form of his life.

Phinney’s teammate Ron Kiefel had won the Coors prologue four of the previous five years, but this time Davis pipped his good friend by two seconds to take the first leader’s jersey at San Francisco’s Coit Tower. Their main challenge appeared to be the feisty Alexi Grewal, leader of the Colorado-based Crest team, who was openly disdainful of the too-often domestically dominant 7-Eleven squad. Tour de France veteran Pablo Wilches led the Colombian Postobon-Manzana professional team, and there was also a Colombian National Amateur team headed up by the up-and-coming Oliverio Rincón to contend with. The Dutch National Amateur team, the U.S. Olympians, and the usual strong domestic squads rounded out a solid if not spectacular field.

7-Eleven’s Jeff Pierce, who led most of the 1987 race before finishing second overall, broke clear to win the opening road race around the Presidio and take the overall lead, but then the amateurs began to shine. U.S. Olympian Craig Schommer used his significant speed to come around Wheaties-Schwinn fast man Tom Broznowski to win the following day’s circuit race in Oakland. Day three was a spectacularly scenic road race through the redwoods of Sonoma County into Santa Rosa, and Schommer’s teammate Gavin O’Grady triumphed from the breakaway while Hampsten took over race leadership. Another Slurpee, Roy Knickman, powered away from a breakaway group for a solo win into Sacramento the following day with no change to the overall. Phinney earned bonus seconds when he notched another win in that evening’s criterium in Old Sacramento, with U.S. Olympian and future teammate Scott McKinley close behind. Hampsten stayed in the lead the following day as Pierce won the nearly 120-mile stage from Nevada City to Squaw Valley in front of Colombian Arcenio Chaparro.

Stage 6a from Squaw Valley to Sparks, Nevada, saw nine riders move clear on the long climb towards Geiger Summit, including 7-Eleven riders Phinney, Kiefel, and Alex Stieda. With Hampsten and Pierce remaining in the main field, this would allow the team to bring more riders up the General Classification—except Phinney and Kiefel were dropped sixty-five miles in. Ahead were danger men Grewal, Wilches, and solid U.S. pro Bruce Whitesel. With only Stieda left in the break, and Pierce and Hampsten seven minutes behind, 7-Eleven was in trouble. Phinney, however, was a stronger and more well-rounded rider in 1988 and chased for eight miles through Virginia City, not only catching back on but ultimately attacking in the final miles to win the stage and move into second overall behind Stieda, the new race leader by 1:04. German Roland Gunther won the evening criterium in Reno, and the race moved into Colorado where Irishman Alan McCormack won the Tour of the Moon stage in Grand Junction.

Grewal lost valued climbing teammates Glenn Sanders and Michael Carter to injury but was far from giving up his challenge and continued to attack at every opportunity. Despite his newfound climbing ability, however, Phinney showed he was still the king of the criteriums, and in Grewal’s hometown of Aspen no less. He spent 42 miles off the front, winning the stage and moving to within four seconds of Stieda’s overall lead. On the following day’s mountainous 107-mile road stage from Aspen to Copper Mountain, Grewal once more led an attack with the Colombians and held a four-minute lead over Phinney at the summit of 12,000-foot Independence Pass. The 7-Eleven squad rallied on the descent, leading a thirty-mile chase to close him down. Wilches survived for a solo win, but Phinney won a mid-race time bonus in Leadville as well as finishing third on the stage (another bonus) to move into the lead by six seconds. Even a downcast Grewal, second on the day and now fourth overall, was complimentary about the way his rival was riding.

Copper Mountain had become Phinney’s second home and the site of training camps with his wife Connie Carpenter, and it was here that he seemed to really start to consider the possibilities of winning. Despite “being pretty much tied with my twin brother Alex”—the one rider who had stayed with him and ridden along to the hospital in that ambulance in Belgium—he admitted he would “really love to win this race.” The next day’s time trial on Vail Pass would be decisive. Climbing specialist Hampsten won, with Rincón, now the KOM leader, just 14 seconds behind in second. Grewal was third, just 27 seconds in arrears, while two minutes further back, Phinney put another 12 seconds into his “twin brother,” and the team now put all their considerable resources behind his victory bid.

Disaster struck that very afternoon in the Vail Village Criterium, one of Phinney’s happiest hunting grounds over the years, and he desperately needed his teammates’ help. He had problems with his rear wheel early on, and Pierce dropped back to give Phinney his bike and then later helped him chase back on. The quest for every Slurpee to win a stage was thwarted when Bob Roll was relegated for an illegal maneuver in the sprint, giving McCormack his second stage victory.

My friends and I traveled down from Wyoming to see the final two stages, the first the Morgul-Bismarck circuit road race outside Boulder and a new final-stage criterium around the campus of Colorado University. The Morgul, named after a local rider’s cat and dog, was a long-time staple in the Coors, and typically the last road stage. In 1988, it was Crest’s last chance to upset the Slurpees. The 13-mile rolling circuit is open, windy, and can get quite hot as riders cover eight laps for over 106 miles. But the biggest features are the two climbs at the finish, first the small but taxing “hump” and then the mile-long “wall” to the finish that gains nearly 350 feet, peaking at 15%. When I first rode it in 1983, some joker had painted “beam me up Scotty” on the steepest pitch! The Crest team put team riders Chris Bailey in the break and Todd Gogulski in a chase group, ready to help when Grewal attacked and bridged up, hoping to erase his 2:20 deficit. He tried repeatedly with mighty attacks up “the wall,” but Hampsten and Phinney thwarted his every move. Phinney then rubbed salt into the wounds by leaving Grewal behind at the finish to take fourth on the stage, ultimately scoring ten top-five finishes in the sixteen stages.

The crowds at CU were massive, reportedly numbering 35,000 to 40,000, which topped the legendary masses that would gather in North Boulder Park. Ron Kiefel broke away with McCormack to ultimately win solo in his stars-and-stripes jersey as reigning National Champion, and Phinney took the field sprint for third. As he joyously thrust his arms skyward to celebrate the overall victory, who should throw his bike at the line just inches behind in fourth? The never-say-die Alexi Grewal, of course, the highest-placed non-7-Eleven rider overall in fourth place. The Slurpees swept the final podium behind Phinney, with Hampsten placing second and Stieda in third. When Phinney was given the keys to the cherry-red convertible BMW awarded the race winner, he joyously handed them over to “Och,” who was delighted.

The crowd parted, the boys all piled in, and team member Inga Thompson jumped in as well. Preparing for her second Olympics, she triumphed over a star-studded women’s field, winning overall by a minute ahead of Kiwi Madonna Harris. Her win in the 264-mile Women’s race, replete with 17,000 feet of climbing, was the first by an American woman since 1983. The 1988 event ended up being the final edition of the storied American race, while Coors stayed involved in cycling, choosing instead to put its marketing dollars into the Coors Light cycling team, seeing the benefits of year-round brand exposure rather than just two weeks in August.

It seemed only fitting that the boy from Boulder who grew up with the race became its final champion, just as the curtain fell on America’s grandest stage race.

Video: La Bicicleta Vieja (The Old Bicycle) – A Documentary

La Bicicleta Vieja (The Old Bicycle) is a documentary about Don Rafa, a bicycle mechanic with a small shop in the Mission District in San Francisco.

The short film (9 minutes, Spanish with English Subtitles) tells the story of Rafael Macias (Don Rafa) and how he came to fix bicycles in his small shop. Sadly, Don Rafa passed away in 2012.

The film is produced by Claudia Escobar, a Columbian visual artist, who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. She is currently a Film Director, Creative Producer, editor, photographer, animator, and illustrator.

The film illustrates a portion of our bicycle economy, where old bikes are given new life by a talented mechanic who has repaired over 15000 bikes in his lifetime. It was featured in the 2011 San Francisco Latino Film Festival. We enjoyed the film and recommend that you watch it too.

Don Rafa’s Cyclery is located in San Francisco.

2929 16th St, San Francisco, CA 94103

(415) 934-1944

Watch:

California Groups Urge CARB to Reinstate E-Bike Incentive Funds After Sudden Cut

November 17, 2025 — A coalition of statewide mobility, climate, and community organizations is pressing the California Air Resources Board (CARB) to reinstate funding for the state’s Electric Bicycle Incentive Project (EBIP) after the program’s remaining funds were abruptly shifted to a car trade-in initiative.

In a letter sent Tuesday to CARB Chair Lauren Sanchez and board members, CalBike and more than two dozen partner groups warned that the move undermines the state’s climate commitments and ignores strong public demand for affordable, zero-emission transportation.

“This is not what climate leadership looks like,” said CalBike Executive Director Kendra Ramsey. “Over one hundred thousand Californians lined up for a modest voucher that would help them drive less, save money, and move freely. Ending that opportunity now ignores that clear demand and walks back hard-won progress.”

The EBIP pilot, a $10 million program aimed at helping low-income residents purchase electric bicycles, had already exhausted its initial funding. According to CalBike, more than 100,000 people attempted to apply or signed up for updates—evidence, they say, of both the program’s popularity and the need for deeper investment.

Coalition members criticized CARB for reallocating the remaining funds without public discussion, arguing that the shift contradicts the state’s stated support for multimodal climate strategies.

The organizations are calling on CARB to restore EBIP funding and recommit to transportation investments that reduce emissions, ease congestion, and lower household costs.

Diné Bikéyah Climbs

By John Summerson — The Diné Bikéyah (Navajo Nation) is the largest Native American reservation in the United States. Spanning parts of three states (Arizona, New Mexico and Utah), it comprises over 27,000 squares miles of desert scrub, towering sandstone cliffs and spires and, in places, tree covered mountains. Though it contains relatively few roads and is sparsely populated, cycling is starting to emerge there.

The long standing Diné (‘The People’ in Navajo) Bike Project is the driving force behind promoting bikes and community wellness on the reservation. Most of the riding is of the off-road variety but there is an annual road race in and around the impressive Chuska Mountains that ends with a solid climb.

The Chuska range is the longest on Navajo land. Straddling the border of Arizona and New Mexico, this is where the most challenging climbs are located. Hot starts in summer, they all end within the trees at altitude and one of them carries the steepest half mile in Arizona. Below are the three most difficult paved ascents on the reservation. This is isolated country so if heading out to tackle these hills or for any extended riding in the area, make sure you carry what you might need.

Buffalo Pass South

Length – 6.3 miles Average Grade – 6.0%

The south side of Buffalo Pass is an isolated and scenic climb in the northeast portion of the Grand Canyon State. A moderate grade greets you to begin the ascent as well as red rock views. Soon the road gets twisty and enters a canyon. Red rock soon recedes to pinyon pine views as well as increased grade. At mile 4.2 the route gets twisty and the grade ramps up to double digit and what is the most difficult half mile of paved climbing within Arizona follows. You will find the maximum grade on the hill here as well. The slope then eases a bit as trees close in as you gain altitude. Towards the top the pedaling gets easy and the climb ends at an unmarked but obvious pass among aspen trees.

Directions – In the small community of Lukachukai on the Navajo Indian Reservation in northeast Arizona, at the junction of Routes 14 and 13, take Route 13 (may be unmarked at junction but it is the main paved road that heads north) north for a few miles to the bridge over Totsoh Wash where the listed climb begins by continuing north on Route 13.

Buffalo Pass North

Length – 8.8 miles Average Grade – 5.1%

The north side of Buffalo Pass is longer but less steep than its south side, resulting in an almost identical ascent regarding difficulty. A shallow grade greets you on the narrow road, gradually getting steeper as you climb. Just over 4 miles in riders will definitely start to feel the slope as larger trees begin to appear. The grade then eases to almost flat before you hit the steepest quarter mile on the hill. From here the grade eases and you will encounter a short descent before moderate climbing resumes up to the unmarked top within trees. The north side of Buffalo Pass is a fun descent as well.

Directions – Approximately 7 miles south of Shiprock, NM on Route 491, head west on Route 13 for just over 20 miles to the Red Valley Chapter House, crossing into Arizona in the process. From the chapter house continue south on Route 13 for 4.2 miles to begin the listed climb where the pavement tilts upward.

Narbonna Pass East

Length – 10.4 miles Average Grade – 5.2%

Once known as Washington Pass, the east side of Narbonna Pass on Route 134 is a very isolated category 1 climb located in western New Mexico close to the Arizona border. It begins as quite shallow (and has contained poor pavement in the past) but soon enters a drainage with increased grade just over one mile into the ascent. After this stretch the grade then tends to alternate between moderate and shallow (but there are no flats or descents on this hill) as you continue to ride west. Eventually a few small trees appear in places along the lightly travelled route. Toward the top a right turn introduces steeper grade and the last two miles are the stoutest of the climb. A few big trees appear with altitude as the road is contained within a canyon near the top. Just before the summit the grade eases and the climb ends at an unmarked but obvious top with a pullout on the left. The west side of Narbonna Pass is a much shorter climb.

Directions – From Interstate 40 in Gallup, NM head north on Route 491 for ~48 miles to tiny Sheep Springs and Route 134 on the left (may not be marked but it is the only paved road heading west). The listed climb begins at the junction by continuing west on Route 134.

Resources:

- Diné Bike Project: https://www.navajoyes.org/dine-bike-project/

- Tour de Rez Cup Series Bike Races (MTB and road): https://www.navajoyes.org/events/

- Navajo Nation Tourism information: https://farmingtonnm.org/listings/navajo-nation

- Navajo Reservation History: https://www.navajo-nsn.gov/history

The World is Coming to America’s Premier Gravel Series

An international roster spanning 11 countries will vie for nearly $600,000 in prize money at the Life Time Grand Prix

The 2026 Life Time Grand Prix roster reads like a passport control checkpoint at an international airport. Eleven countries. Five continents. All converging on America’s dusty gravel roads for what promises to be the most competitive season yet of the nation’s premier off-road cycling series.

When the dust settles after six races spanning from May through October, one rider will walk away with a significant chunk of the record $590,000 prize purse. But getting there means surviving everything from the high-altitude punishment of Colorado’s SBT GRVL to the brutal heat and endless horizons of Kansas at UNBOUND Gravel.

This year’s international invasion is unprecedented. Nearly half the field—19 of 44 riders—hails from outside the United States, representing everywhere from Argentina to South Africa, Norway to New Zealand. The series drew applications from an astounding 24 countries, a testament to gravel racing’s exploding global appeal.

The Women to Watch

On the women’s side, all eyes will be on defending series champion Sofía Gómez Villafañe, the Argentine powerhouse chasing her fourth consecutive Grand Prix title. But she’ll face her toughest field yet.

Polish gravel ace Karolina Migoń enters as the reigning UNBOUND Gravel 200 champion and back-to-back winner of The Traka 360, one of Europe’s most punishing gravel events. Germany’s Rosa Klöser also conquered UNBOUND in 2024 and racked up eight victories in 2025 alone.

The field includes seven Grand Prix rookies, among them 22-year-old Ruth Holcomb, who dominated the U23 competition in 2025 and earned her spot in the big show. Veterans like Lauren Stephens, 39, and Paige Onweller, 36, bring decades of combined racing experience to a roster that spans continents and generations.

2026 Women’s Field:

Morgan Aguirre, 32, USA

Lauren De Crescenzo, 35, USA

Cecily Decker, 27, USA

Maude Farrell, 34, USA

Sofía Gómez Villafañe, 31, Argentina

Stella Hobbs, 32, USA

Ruth Holcomb, 22, USA

Rosa Klöser, 29, Germany

Sarah Lange, 34, USA

Emma Langley, 30, USA

Cecile Lejeune, 27, France

Karolina Migoń, 29, Poland

Paige Onweller, 36, USA

Hannah Otto, 30, USA

Hayley Preen, 27, South Africa

Melisa Rollins, 30, USA

Ruby Ryan, 24, USA

Samara Sheppard, 35, New Zealand

Courtney Sherwell, 37, Australia

Alexis Skarda, 36, USA

Lauren Stephens, 39, USA

Sarah Sturm, 36, USA

International Men’s Field Stacked with Talent

The men’s competition brings back defending champion Cameron Jones of New Zealand and three-time winner Keegan Swenson, but they’ll face serious challenges from a globally diverse field.

Germany’s Andreas Seewald, the reigning European Mountain Bike Champion, makes his series debut alongside Norway’s Simen Nordahl Svendsen, who claimed the 2024 Gravel Earth Series title. Switzerland’s Jan Stöckli, runner-up at this year’s Traka 360, adds to a European contingent that includes three Norwegian riders and three from Switzerland.

South Africa sends two riders, including Matthew Beers and Marc Pritzen, while Australia’s Brendan Johnston and Canada’s Andrew L’Esperance ensure the Commonwealth is well represented.

Griffin Hoppin, just 22, earned his spot by winning the inaugural U23 program in 2025—proof that Life Time’s development initiative is already paying dividends.

2026 Men’s Field:

Matthew Beers, 31, South Africa

Zach Calton, 28, USA

Cobe Freeburn, 24, USA

Griffin Hoppin, 22, USA

Brendan Johnston, 34, Australia

Cameron Jones, 25, New Zealand

Andrew L’Esperance, 34, Canada

Bradyn Lange, 26, USA

Payson McElveen, 32, USA

Simen Nordahl Svendsen, 26, Norway

Kyan Olshove, 23, USA

Cole Paton, 28, USA

Simon Pellaud, 33, Switzerland

Marc Pritzen, 26, South Africa

Torbjørn Røed, 28, Norway

Andreas Seewald, 34, Germany

Felix Stehli, 25, Switzerland

Anton Stensby, 24, Norway

Jan Stöckli, 26, Switzerland

Caleb Swartz, 26, USA

Keegan Swenson, 31, USA

Alexey Vermeulen, 31, USA

The Wild Card Gambit

The series maintains its Wild Card program, offering one final shot at glory for riders who didn’t make the initial cut. Athletes who applied for the series can earn their way in by competing at both Sea Otter Classic Gravel and UNBOUND Gravel 200, with the top three finishers in each category joining the field.

It’s a high-stakes qualifier that adds drama before the official series even begins, turning April and May into must-watch racing.

Growing the Sport

Michelle Duffy Smith, Vice President of Marketing for Life Time and Executive Director of the Grand Prix, sees the international roster as validation of the series’ meteoric rise.

“The 2025 season was incredibly competitive, but 2026 is shaping up to be even bigger,” she said. “This roster takes the series to another level. It’s been exciting to watch this community grow globally.”

That growth comes with expanded live coverage and increased support for athletes, alongside the massive prize purse that makes the Grand Prix one of the richest events in gravel racing.

The U23 program returns for 2026, with overall winners automatically qualifying for the 2027 series—a clear pathway for the next generation of gravel stars.

When the season kicks off in May, the start line at UNBOUND Gravel will showcase what gravel racing has become: a truly global phenomenon, where riders from Polish villages and Argentine cities, Norwegian fjords and South African highlands, all chase the same dream across America’s endless gravel roads.

For more information, visit lifetimegrandprix.com or follow @LifeTimeGrandPrix on Instagram and YouTube.

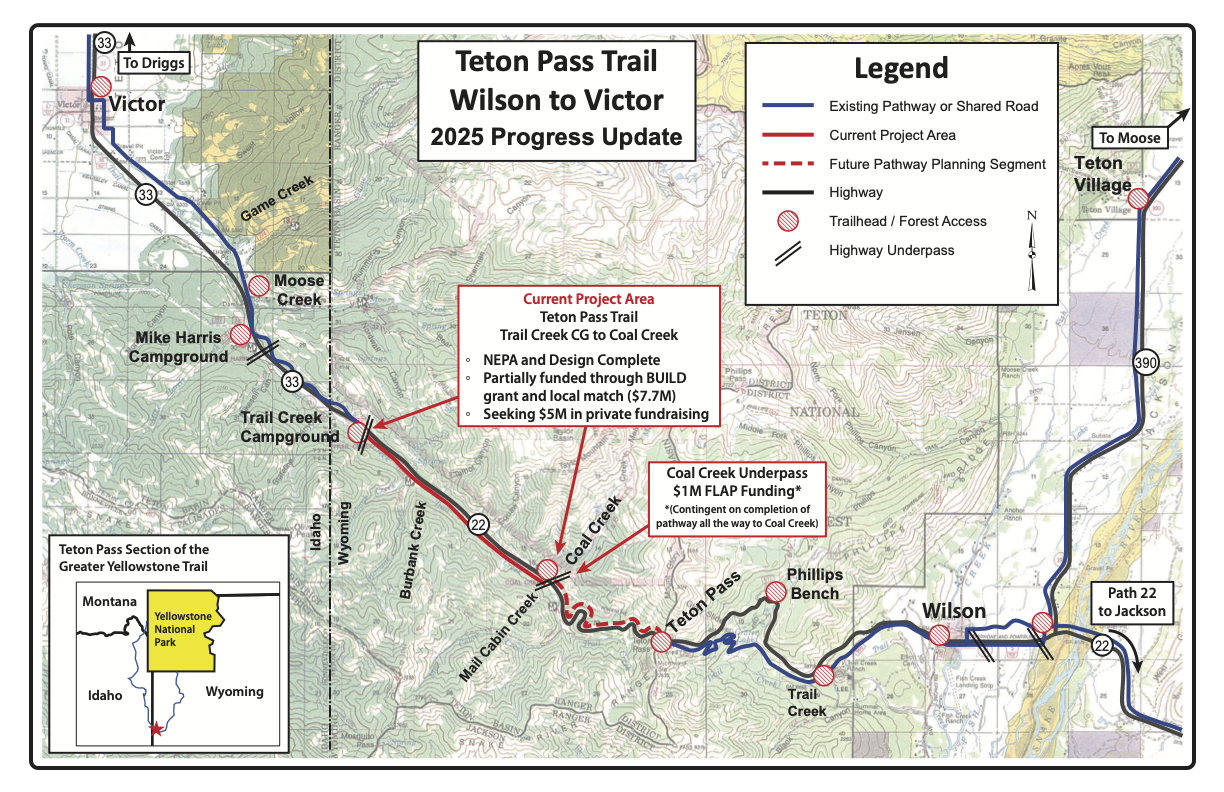

The Teton Pass Trail’s Most Audacious Section Yet to Be Built

A $5 million fundraising push aims to complete a technically complex 3.6-mile segment linking Wyoming and Idaho’s Teton valleys

A regional coalition is racing to raise $5 million by year’s end to build what engineers are calling the most technically ambitious pathway ever proposed in the Tetons—a 3.6-mile non-motorized trail segment connecting Trail Creek Campground to Coal Creek Trailhead on the west side of Teton Pass.

The Trail Creek-to-Coal Creek section has been engineered, permitted, and approved. If the fundraising succeeds, construction would begin when snow melts in spring 2026.

“This is a once-in-a-generation opportunity,” said Dave Bergart, campaign lead from Victor, Idaho. “The Teton Pass Trail is the most ambitious pathway project in the history of both Teton Counties.”

The new segment represents a critical gap in the Greater Yellowstone Trail, an 180-mile network connecting Jackson Hole, Teton Valley, and West Yellowstone. Currently 85% complete, the route links communities through pathways, forest roads, and small-town connectors. The Teton Pass section tackles some of the region’s most challenging terrain, navigating steep slopes and wetlands with extensive retaining walls to route the pathway between Trail Creek and Highway 22.

While cyclists and hikers will gain a premier summer route, winter users stand to benefit significantly. The planned Coal Creek underpass will improve year-round safety at one of the Pass’s busiest trailheads, serving hundreds of backcountry skiers on powder days. The pathway will also provide a dedicated off-highway track for skiers returning from popular runs like “the Do-Its,” separating them from vehicle traffic.

Almost $8 million of the $13.5 million total budget is already secured through federal grants and local government funds. The final $5 million will unlock an additional $1 million in Federal Land Access Program funding to ensure the Coal Creek underpass can be built as part of the project.

The effort is led by Save Teton Pass Trail, a volunteer coalition including Friends of Pathways, Teton Valley Trails and Pathways, Teton Backcountry Alliance, Mountain Bike the Tetons, and multiple local governments and businesses.

Donations and project information are available at TetonPass.org.

The Athlete’s Kitchen: Athletes, Food & Fear of Weight Gain

By Nancy Clark MS RD CSSD — As a sports nutritionist, I spend too many counseling hours resolving weight concerns of athletic people. Females and males alike come to me, trying to figure out how to lose weight. The eat less and move more paradigm doesn’t always work. Weight is more than a matter of will power.

Despite restricting their food intake, some athletes aren’t losing weight. They ask if they are they are eating too much. Others wonder if lack of weight loss is because they are eating too little. Both feel frustrated their bodies defy their attempts to shed fat.

Athletes who under-eat can be experiencing Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). Relative energy deficiency happens when an athlete eats well—but not enough to support both normal body functions and the demands of exercise.

REDs is a constellation of symptoms (including eating disorders/disordered eating, stress fractures, low libido (men), amenorrhea (women), depression, hormonal imbalance, and altered metabolism) that can impair overall health and performance. Despite consuming, let’s say, 2,500 calories a day, a female athlete can still have an energy (calorie) deficit relative to how much fuel her body actually requires. Over the long term, this Low Energy Availability (LEA) contributes to the symptoms associated with REDs.

- Athletes can be in a state of low energy availability and still remain weight stable, despite having undesired body fat. They (understandably) become frustrated at lack of fat loss despite their efforts to slim down. As one runner said, “I should be pencil-thin by now, for all the exercise I do…”

- The body does an amazing job of conserving energy and curbing fat loss when food is scarce. Signs of energy conservation include chronically cold hands and feet; irregular or no menstrual period in women; low libido with no morning erection in men. Constant food-thoughts (e.g. finishing one meal only to start thinking about the next one), trouble concentrating, and poor sleep are also signs of LEA.

- LEA can happen unintentionally due to lack of nutrition knowledge about how much an athlete “deserves” to eat. Because we live in a food is fattening culture, hefty meals often get negatively scrutinized. (“You’re really going to eat that much food???”). Female endurance athletes commonly need more than 2,400 calories a day and males more than 2,800 depending on their body size, sport, and training hours.

- For athletes fearful of weight gain, selecting this amount of food can become a daunting challenge without a structured food plan, particularly for athletes who “eat healthy” (i.e., no added sugar, fat or “fun foods”). They can easily fail to consume enough calories because a high-quality diet (based on lean proteins, fiber-rich veggies, whole grains, and fruits) is filling and curbs the appetite. Suggestions: Eat more nuts, olive oil and even some fun foods. A reasonable target is 85% to 90% quality calories and 10% to 15% fun foods. Yes, when you need a lot of calories, it’s okay to plan in a few sweets and treats.

- LEA also happens with intentional food restriction, as with dieting, disordered eating and eating disorders. Other barriers to increasing food intake can include lack of time to prepare/eat the food, as well as lack of money to buy the food. Chronic food restriction means reduced consumption of not just calories but also vitamins, minerals, protein, and bioactive compounds that promote a strong immune system, health, and performance. LEA can potentially lead to yet-another injury and ruin an athlete’s career. Recovery from chronic LEA can take months (to regain menstrual status) and years (to restore lost bone mineral density).

- “Just eat more” is not the simple solution for LEA among athletes who have a poor relationship with food and fear weight gain. While they may want to eat “normally,” they can experience high anxiety. After all, “How can I eat more calories and not get fat?” (Answer: Your body will stop hibernating. You will feel warmer, more energetic, and overall perkier.)

- Knowing how much is okay to eat—your calorie budget— can be helpful information and give context to information on food labels. For example, a 250-calorie energy bar is too little when your calorie budget is 400 calories per snack. Most athletes under-estimate their required energy (calorie) needs and also under-estimate how many calories they burn during exercise. Hence, they can find it eye-opening and very helpful to learn their actual calorie requirements. Knowing how much is okay to eat can boost food intake—guilt-free!

- That said, calorie education alone is unlikely to inspire all athletes to increase their food intake. That’s because eating more than usual can be scary. In a stud6 (1), 62% of 55 female athletes with LEA reported being afraid their weight and body shape would change and hurt their performance. Yet, adding just 300 to 350 calories a day can lead to resumption of menses in the majority of women —without needing to cut back on their training. Adding those calories before exercise can feel like a “safe” time to do so.

Research indicates any weight gain (related to the added calories) tends to be minimal. A small (2-10 lb) increase in body weight may be required to induce menstrual recovery—and the benefits are worth it! - Don’t let fear or shame get in your way of seeking food-help. Two-thirds of the athletes with LEA reported they welcomed the support of a sports nutritionist who educated them about their calorie needs, helped them develop an eating plan, and supported the implementation of the plan. If you are now inspired to talk with a local sports nutrition professional, find one who is a Registered Dietitian (RD or RDN) and a Certified Specialist in Sports Dietetics (CSSD). The referral networks at org or healthprofs.com are helpful.

No need to feel shame for seeking help. Making seemingly simple dietary changes can be hard and an understanding RD CSSD can help you make changes more easily.

Reference

- Matkin-Hussey, P, D Baker, M Ogilvie, S Beable and K Black. The barriers and facilitators of improving energy availability amongst females clinically diagnosed with Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2024 Dec 02